Published

8th January 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –8th January 2024

After the party, the hangover

The first week of January feeling was eerily reminiscent of one year ago: strikes, endless rain and then everything else that causes the usual January blues. Yet investors in diversified global investment portfolios will get a positive surprise when they look at their end-of-year valuations. All bar the most bond-heavy investment strategies will have not only provided them with positive returns, but even outstripped what was available from cash deposits or what inflation took away in purchasing power. On top of this tidy 2023 Christmas present, this year’s outlook is much less about dreading recession than the real possibility of an economic upswing.

During a year that was for most of it defined by its volatility rather than direction, the last two months brought a welcome change in investor sentiment. We go into detail in the asset returns review for December this week, but the change came about with the sustained fall in the rate of inflation around the globe, which permitted central banks to put an end to their relentless rate rises as they sensed victory in their fight against the post-pandemic boom inflation.

The resulting rush towards long-term assets pushed bond yields down to a 27th December low point of 3.45% for the 10-year gilt and 3.78% for the 10-year US Treasury, having reached 4.75% and 5.0% highs respectively only a few months ago. Those yields were achieved in the very low volumes between the major holidays.

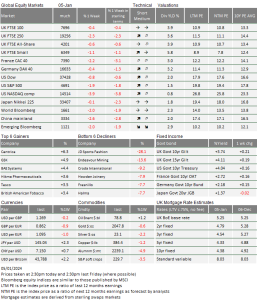

Both equity and bond prices fell back last week as trading volumes normalised. Fixed-coupon bond yields rise when prices fall, and both UK and US yields are up quite sharply, currently at 3.80% and 4.05%, respectively. Equities have also responded in their usual way (at least, usual for the past few years) of falling back some 1%-2% through the course of last week, with some notable underperformance from tech-related stocks.

So, after the Christmas party, January perhaps started with a bit of a hangover. Professional investors, like us, seem to have looked at the lower yields on bonds and larger cap equities and decided to take the near- term profit. In part, this may well be because they are making space in portfolios for potential new investment positions. Companies are seeing the lower cost of capital as an opportunity to finally replenish funds with new bond issues, and equity issues in the form of initial public offerings (IPOs) and convertible bonds. The renewed interest in convertible bond issuance is interesting, and indicates investors find the combination of bond-like downside protection with equity upside appealing.

Contrary to the hangover feeling of investors, however, such behaviour is born of optimism rather than pessimism. Companies want to raise capital because their business can generate a better return than the cost of that capital (even at these relatively higher rates than in the past few years) and investors believe in the new opportunities. It also suggests that capital markets are more in balance now than they were in December, when optimism rose but corporate treasurers wanted to wait until the new year.

Large-cap tech stocks encountered weakness for other reasons this week. Barclays Capital will be heartened by the amount of coverage that Tim Long and his analyst team received after they published a piece saying iPhone sales were stagnating, cutting their recommended Apple position to “underweight”. ASML was hit after it voluntarily halted shipments to China of high-end chip production equipment.

Perhaps the tech story is also about profit-taking. The artificial intelligence theme held sway for much of 2023 while it was difficult to find upside prospects elsewhere. However, when we look through the revisions to earnings across almost all sectors, the past three months have seen a resurgence of optimism. Analysts’ earnings expectations in all sectors bar energy have risen, and that sort of breadth is more usual after an economy exits from a recession. Last year, it was really only the tech sector that saw substantial earnings optimism.

We will enter the Q4 earnings season very shortly. On the back of falling yields and rising equity valuations, financial conditions eased substantially through that quarter and there are few hints of stress. There will be inevitable shocks and companies will tell us that the environment remains tough. At the same time, most will tell us they are doing well relative to their peers and beating expectations. The earnings announcement season should not disturb investor optimism.

The real news of the week was that the narrative of global policy rates being cut sometime in the second quarter took a bit of a hit. European inflation data was in line with, but not below expectations while US employment remains tight. US December unemployment stayed the same as November’s very surprising low 3.7%. Indeed, the evidence is that employment tightened at the end of the year, something that should bolster consumption but will do nothing to reduce robust wage growth.

Economic optimism doesn’t help bonds. Low inflation data may help for this month, and possibly next, but rate cuts in March and April look as far-fetched as we thought they did at the tail end of last year. However, the rise in bond yields occurred in the longer rather than the shorter-dated maturities. By our measure, longer bonds are mildly expensive after the recent yield falls and more vulnerable to issuance pressures even if inflation data stagnates for a while rather than continues to fall. However, given the still calming inflation dynamics, bond yields are not likely to repeat the falls of the end of 2023 in the next quarter.

China continues to behave in a radically different way to the rest of the world’s stock markets, an indication of peculiar stresses and policy differences. Last Friday, Zhongzhi Enterprise Group (ZEG) – formerly the largest of China’s trusts for public investment – filed for bankruptcy. ZEG had made its troubles known in the autumn, so this move may not cause more problems directly.

China’s trusts took deposits from companies and wealthy individual investors and companies, often then leveraging this capital to invest in stocks and bonds and to make loans. Known as shadow banks, these institutions accounted for almost 10% of total loans in China in the lead-up to the pandemic, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Their shadow banking activities have been important for China’s private sector economy; firms that can’t access traditional banks having depended significantly on such trusts for loans. They have also been central for domestic stocks, providing a major channel for household equity investment, at least for the wealthy. Perhaps then, it is unsurprising that the malaise among these trusts goes hand-in-hand with weak private- sector loan growth and weak domestic stock market investment.

For Chinese stocks, a lack of domestic investors may mean that profitable good-quality companies are valued cheaply and present a great opportunity for foreign investors. Signs are that foreign investor flows have started to turn positive after a long period of disinvestment. The potential flashpoint of the Taiwan presidential election is on 13th January and the most pro-independence candidate (Lai Ching-te, also known as William Lai) seems likely to win, although it is not a certainty. Perhaps China may look more attractive once we know more about where Taiwan’s politics will lie.

December 2023 asset returns review

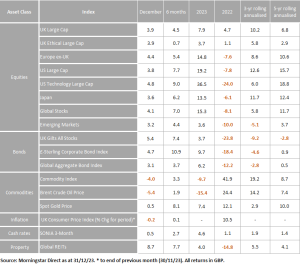

The proverbial ‘Santa rally’ was on many investors’ wish lists, and Christmas 2023 certainly delivered. Not only were returns strong virtually across the board in December, but upward moves seemed to increase further as the month progressed – including a burst of cheer into the close for Christmas. It was a continuation of the good feeling that swept capital markets in November, with investors hopeful about financial conditions and the global economy for 2024. Inflation is substantially and unmistakably lower than feared last year, and central bankers have recognised this. Policymakers continued to hint at looser policy stances in 2024, leading to a 3.7% monthly gain for global stocks in sterling terms. The table below shows December’s results across major regions and asset classes.

There was a notable consistency across regional equity returns, with most headline indices gaining around 4% in sterling terms through December (with the glaring exception of China, which we get to later). This reflects the general improvements in expected monetary policy, which pushed bond yields down significantly and made all risk assets more attractive by comparison. UK 10-year yields, for example, ended 2023 almost exactly where they began, despite a huge move up in the first half of the year. Some of the so-called ‘peripheral’ European nations even ended the year with lower yields than 12 months ago.

We suspect that end-of-year readjustments played a big part here. Investment managers naturally reassess their positions at key points like year-end, with a particular focus on reducing risks. It is likely that, after an uncertain and at times difficult year for the global economy, many traders had short positions (i.e., those that make money on market declines) which had to be squared-off. Since this came at a time when general risk sentiment – and indeed economic expectations – was improving, it meant an optimistic market shift.

Expected interest rate cuts were perhaps the biggest part of this adjustment, but were far from the only part. We formulated our own 2024 outlook last month – many investment houses no doubt did the same – and this occurred when cyclical expectations finally seemed to be turning. The outperformance of Europe and Emerging Markets (EM) – excluding China – showed that investors are not only excited about the prospect of lower rates having a positive impact on risk asset valuations, but also the near-term economic growth opportunities this might bring. European equities gained 4.3% in sterling terms through December, while EM ex-China gained an impressive 5.1%.

In the same vein, the UK’s small and medium-cap equities outperformed their larger-cap peers, with an 8.2% gain against the latter’s 3.9%. Returns for both indices were decent, meaning 2023 ended fairly well for UK stocks despite myriad economic and monetary policy worries. The outperformance of smaller businesses, which are more oriented toward short-term growth, shows that a domestic cyclical turn is now expected. That has gone hand-in-hand with a fall-back in UK bond yields and expected interest rates, despite the Bank of England (BoE) signalling it wishes to stick with higher rates for a while yet. As we wrote in our 2024 outlook, it seems investors do not believe the BoE’s sterner messages, thanks to the underlying weakness in the UK economy.

Rallying bond prices were the greatest support to equity valuations in December, as they were in the previous month. But as noted, falling yields (the inverse of bond prices) were not a response to weakening growth expectations since the latter held up well. Falling nominal yields were instead a reflection of significantly lower price pressures, and hence a general move down in inflation expectations. Weak energy and goods prices proved the biggest source of disinflation, as was the case for most of 2023. Lately, though, the feeling is that these weaknesses will persist.

China is a huge part of that story. The world’s second-largest economy was the only major equity market that posted negative returns for December, falling 3.1% in sterling terms, and continuing the trend of Chinese growth and financial markets being completely out of sync with the west. Growth was severely hampered last year thanks to weak domestic demand and weaker foreign demand for Chinese goods – particularly from the US.

Historically, Beijing responds to such weaknesses with massive policy stimuli, but this time the policy response was stop-start at best. In particular, the central government was unable to cut back production in the face of this weak demand, meaning it was essentially pushing oversupply out to the world. This was certainly the case for goods, but weaker Chinese demand for energy has acted – and will likely continue to act – as a swing factor for global energy markets, moving them toward oversupply and hence lowering global prices.

That said, more recent policy signals coming out of China were more decisively pro-growth. This led to a slight pickup in Chinese asset prices into the end of December, and should bode well for 2024. A revving of China’s growth engine will help not just the country itself but global growth in general. We suspect this is a big part of stronger growth expectations as we start the new year, particularly for EMs. It is telling that, even with severe equity disappointment and global growth concerns in 2023, EM equities managed to end the year 4.4% up in sterling terms.

In general, investment returns for 2023 were overwhelmingly positive. This outcome looked unlikely even just a few months ago, when investors feared central bankers’ ‘higher for longer’ mantra. Moreover, we take heart that the leading lights of the Santa rally were those that suffered before: small and mid-cap equities, and corporate bonds. The lows of last year were not bad enough to cause too much pain, and now the green shoots of a recovery are in sight. Santa brought us a soft landing after all.

US election: will Trump shake markets?

There is an established truth in international politics that when America votes, the world watches. The historical reason is simple: as the world’s preeminent superpower, no country’s internal politics has as global an impact as the US. Ever since Donald Trump announced his first presidential campaign in 2015, though, melodrama has given global audiences another reason to tune in. And with criminal charges piling up against the former president – but not even scratching his campaign for his party’s candidacy – the 2024 election is sure to be Trump’s most dramatic yet.

Strangely, though, that established truth does not usually extend to investors. In fact, capital markets often sail through politically turbulent elections without much volatility. Looking back, the 2020 election had little impact on the US stock market either before, during or after the fact. This was despite an extremely politically volatile campaign that ended in accusations of fraud and an attempted insurrection. Trump’s shock victory in 2016 initially knocked US equities, as investors feared the destabilising effects of a divisive political novice in the White House, but this downturn was recovered within days and markets later surged in what was wryly called the ‘Trump rally’.

The big question as we head into this election year is: can markets ignore US politics again? Judging by market reactions – or lack thereof – to Trump’s myriad legal troubles in 2023, it seems possible they can, but it is hard to analyse because of a lack of clarity about implications regarding market expectations. It could be that markets think legal issues will prevent Trump from winning (or perhaps even featuring on) the 2024 presidential ballot and are happy about it. It could be that they think his chances of winning are completely unaffected by legal battles – meaning there is no new information to move asset prices. Alternatively, it could be that they see the 2024 election winner as having no effect on expected investment returns.

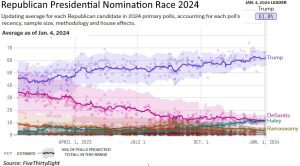

Each of those views make some sense, but they are all loaded with uncertainties. Many think that Trump gaining the Republican Party candidacy, and thereby featuring on national presidential ballots, is inevitable but, while it is a likelihood, it is not a certainty. Trump has a dominant lead over Republican rivals, but his legal battles – in particular cases relating to his attempts to overturn the 2020 election result – could still sink his campaign.

The states of Colorado and Maine have already moved to ban Trump from the 2024 ballot under the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution, which prohibits candidates who have engaged in acts of insurrection. They say this applies to Trump because of his role in the 6th January 2021 riots. These rulings are expected to be quashed by the conservative-dominated Supreme Court, but that in part depends on what happens in related cases before the election. If Trump is convicted of election fraud (as he might well be in Georgia), even the most conservative Supreme Court judges might struggle to clear him of sedition. Even if they do, the drain on legal fees and potential wider support might be enough to knock him off his perch.

That said, there is a growing feeling that, if Trump makes it onto the ballot, he will likely win in November. This is supported by his polling lead against President Biden, both nationally and in key swing states. Again, there are many unknowns here – including whether Biden himself will feature on the ballot, and whether economic improvements might rescue his dire popularity ratings before polling day. But a second term for Trump is certainly enough of a likelihood that investors and American citizens have to seriously consider it.

For many Americans – and the majority of those in urban areas – the thought is extremely unpalatable, to put it mildly. There is no doubt the US public is more divided than it has been in generations (in 2022, 40% said they expected a civil war in the next decade, and that was before the Trump indictments), and while the Trump faithful have long hyperbolised the Democratic Party, it is now common for Democrats to warn of Trump’s existential threat to democracy as well.

Now, what matters for answering the original question – how markets will fare this election year – is not whether those pronouncements are true, but that many Americans believe them. In particular, there is a large group of liberal-leaning highly educated urban dwelling citizens who think a second Trump presidency – combined with a radically conservative Supreme Court – could destroy the liberal democratic institutions that keep the republic running. That demographic tends to skew wealthier than rural less educated counterparts and, as such, makes up a much larger proportion of US domestic investors.

If those investors are scared that the very fabric of the country might unravel, they are unlikely to want to pour more of their savings into asset markets. But as we have written extensively before, the stunning US market returns over the last few years – relative to other regions – have been largely sustained by Americans’ willingness and ability to invest those savings. The other major part of US outperformance has been its attractiveness to foreign investors, but domestic investors remain the majority shareholders of corporate America. If they get spooked foreign inflows will struggle to make up for it.

To be clear, we are not saying the Trump scare will lead to a financial meltdown, much less a recession. Corporate profits are much too strong, and the background credit environment has improved too much (thanks to the Federal Reserve) for that to happen. But we have written much recently about the prolonged outperformance of the US, and whether it can continue now that its assets have become much more expensive compared to Europe and EMs. A change of market fortunes, as we argued before, needs a catalyst. Half the US fearing the death of democracy could be such an event.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.