Published

7th October 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

Why are markets so calm?

Raised tensions in the Middle East dominated the headlines last week. Capital markets are obviously not the most humanly important consideration in this situation, but our job as investment managers is to think about how they might react. Initially, global stocks sold off slightly after the news, while oil prices gained 5% from the year’s lows. The dollar recovered about half of its recent decline against almost all currencies. But overall, compared to history, we would characterise this reaction as surprisingly mooted.

We had more oil price gains on Friday morning, once it became clear that Israel wishes to target Iran’s oil production. The US dollar gained – usually a ‘risk-off’ sign from markets. But low-risk US treasuries are down in price, while higher risk assets remain in demand. One might think this a counterintuitive response.

It is only counterintuitive if one thinks the recent growth signals from the US and from China will be overwhelmed by the Middle-Eastern impacts. Markets clearly think this is unlikely. Friday’s US employment data suggests the labour market is strengthening, while there are reports of strong consumer spending during China’s week-long holiday.

On balance, we did not and do not expect that the Israel-Iran conflict will have long-lasting impacts on asset prices. Currently, markets are more preoccupied with global growth and monetary policy and, in that respect, the outlook has continued to improve during the past week.

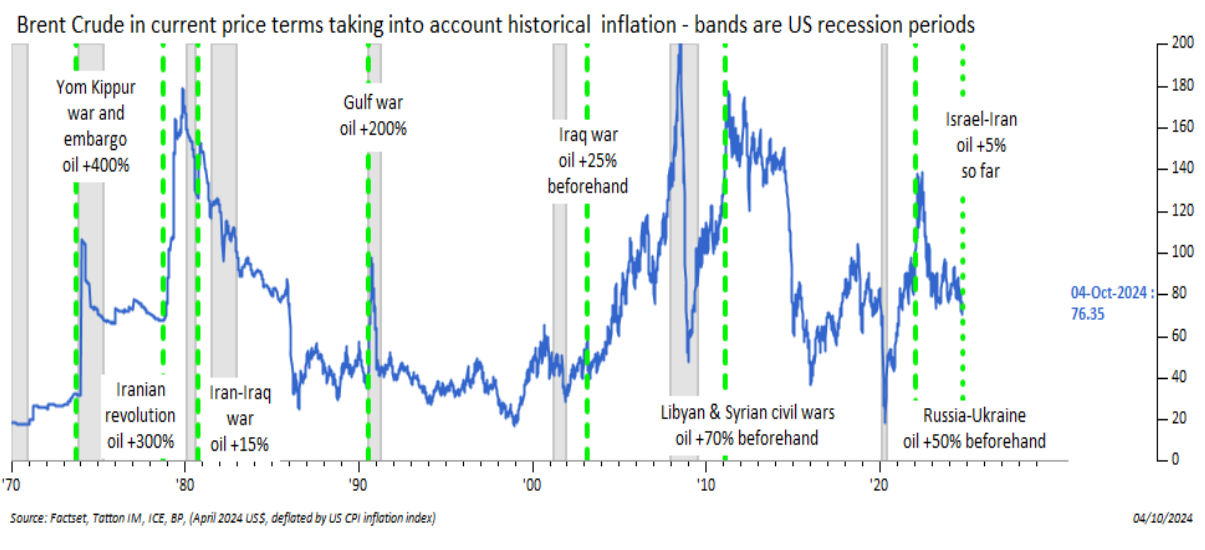

Oil prices are full of uncertainty, but supply is plentiful

In general, the lasting market impacts of Middle Eastern conflicts come through oil prices. The oil shock begun by the Yom-Kippur war of 1973, and consequent Arab oil embargo on Western nations, saw a 400% rise in crude prices. In the last 30 years, there have been two major global conflicts that caused oil prices to spike: Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, and Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The Gulf War spike was short lived. The Ukraine war has had a longer impact and restructured global energy markets, but this has mainly related to natural gas. Oil prices returned to ‘normal’ in less than a year

Crude oil and Middle-Eastern conflicts

We would caution any direct historical comparison, however. A full war between Israel and Iran would be a different story, particularly if it coincided with a Saudi-Iran conflict. US President Biden cautioned Israel against targeting Iran’s nuclear sites, but is reportedly considering backing Israel’s plans to hit oil refineries (Iran is OPEC’s third-largest producer).

We are not oil experts, but there are clear risks for global oil supplies. Still, that risk needs to be seen in the context of the current global oil oversupply. Saudi Arabia is loosening supply constraints, supposedly to regain market share that it lost to non-OPEC producers and less disciplined OPEC+ members. Libya’s political situation has recently allowed its oil supplies to come back onto the market too. All of this is happening while global oil demand has been sluggish. We were fairly confident that oil prices would stay subdued for those reasons, before the recent escalation. Tensions last week introduce uncertainties, but probably do not change the fundamentals too much.

Monetary policy getting easier – but will it work the same? As usual, markets are more preoccupied with central banks. We have known for a while that the US Federal Reserve is dovish (preferring lower interest rates) but last week we got encouraging signals from other central banks. Bank of England (BoE) Governor Andrew Bailey said last Thursday that rate cuts could get “a bit more aggressive” if inflation pressures keep coming down. Sterling had previously been strong, as markets thought the BoE was more hawkish than its peers (higher UK rates encourage people to keep their money here, pushing up sterling), but Bailey’s comments sent sterling down more than 1% against the dollar.

Markets are also betting on another European Central Bank (ECB) cut this month, after ECB president Lagarde expressed increasing “confidence that inflation will return to target in a timely manner”. Meanwhile, Japan’s new Prime Minister Ishiba seemingly pressured the Bank of Japan into maintaining its near-zero rates. In general, global central bankers seem confident that inflation – particularly wage inflation – is now contained, and policy can become more supportive. That is good news for global liquidity.

We are positive about this, but would add a note of caution about liquidity. Ever since the 2008 global financial crisis – and particularly during the pandemic – we became used to the quantitative easing style of central bank liquidity creation: flooding the system with money by buying bonds. That is clearly not happening now (in fact the opposite, quantitative tightening is still in force). Liquidity creation now is more old fashioned: ease financing rates and let the commercial banks create money themselves. The banking system is not what it was, so the transmission of liquidity might not be as strong. Still, this is a positive for the economy and risk assets.

But the US economy may be too strong for the Fed to remain dovish

Even before China’s new policy stimulus, global and regional financial conditions had eased considerably, benefitting the economy. This is most apparent in the US, where the September employment report showed returning growth. Economists expected a moderate increase in the US non-farm payroll (the nation’s standard jobs measure), adding an extra 150,000 jobs. The actual increase was 254,000. The non-farm data often produces surprises like this, but it was meaningful all the same. Unemployment fell back to 4.1% from 4.2% and average hourly earnings grew 4% year-on-year.

This data is clearly stronger than the previous few months and confirm what the more patchy employment data had already suggested: the recent soft patch bottomed in the summer and confidence is growing. Pay growth has stabilised and is ahead of inflation, supporting consumption into the year-end.

Fed chair Jerome Powell spoke early last week, saying interest rate cuts would be moderate (as we predicted previously, contrary to market pricing). Bond yields rose after his comments, and again following the employment data: 10-year yields are back near 4% and markets now expect the Fed funds rate to end 2025 at 3.5%, versus 3.25% recently. But markets think rate cuts are still on the table – as the non-farm payroll often moderates after positive surprises.

Commentators talk about “soft-landing” where the economy settles at a sustainable level, then trundles along. The US may have already landed so softly that we didn’t feel the wheels touch the ground. If so – absent energy inflation shocks – today’s strength in risk assets is entirely justified.

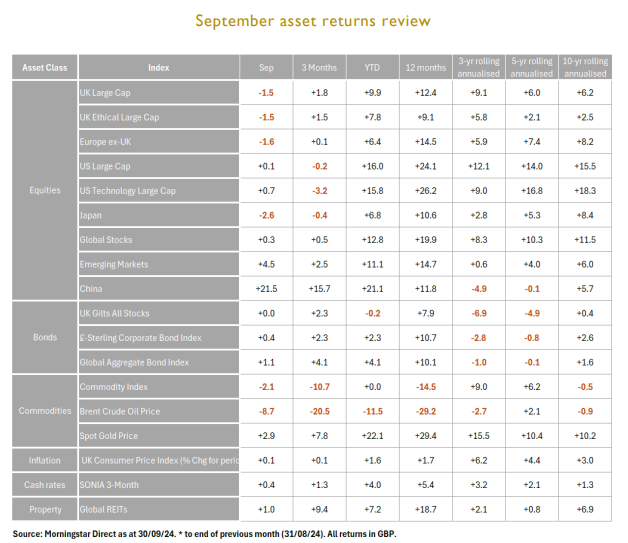

Global stock returns were virtually flat for sterling-based investors last month – up 0.3%. On the face of it, this is somewhat surprising. We started September with the US Federal Reserve continuing to suggest it would be dovish (preferring lower interest rates), which it later made good on by delivering a 50 basis point (bps) interest rate cut. We ended the month with China promising monetary and fiscal stimulus – in a genuine attempt to address its domestic demand problem. Both of those are strong positives for global growth, and yet monthly returns were sluggish. This has to be seen in the longer-term context, though: global stocks have gained 12.8% year-to-date in sterling terms, and 26% since last year’s October sell-off.

September started in the same fashion as August – with a bump. Markets sold off in the first week on global growth fears, centred on China’s continued malaise but tinged with US employment concerns. Just like in August, stocks spent the rest of the month recovering, once investors realised that the medium-term global growth picture is decent, and that risk assets should be supported by interest rate cuts. In fact, monthly global stock returns were more clearly positive in dollar terms – but were held back for sterling investors by the strengthening of Britain’s currency during the month.

The Federal Reserve’s larger-than-usual rate cut was one of the main market stories for September. Some expected the Fed to cut by the more standard 25bps, so the 50bps move was presented as a ‘surprise’. But chairman Powell noted that the committee would have cut rates for the first time in August, had it known the weaker employment data that came out just after that month’s meeting.

We should therefore interpret the 50bps move as a ‘catch up’, rather than a signal of intent. Bond markets nevertheless moved to price in several Fed cuts into next year. We judge markets’ implied rate cut expectations as a little steep, given the US economy is resilient and probably does not need as much monetary loosening. But the Fed has shown a clear loosening bias for the near-term, which will support stock valuations.

China’s monetary and fiscal stimulus packages – announced recently – were the other major market movers in September. Beijing’s announcements came just days after the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) appeared to signal tighter policy, an event which led investors to abandon hope for a policy-led rebound in Chinese demand. That U-turn is why Chinese stocks gained so strongly – ending the month 21.5% up in sterling terms, by far and away the best performer. The unpredictability is also why China led the volatility charts in September. This reflects what Chinese stocks are right now: they could be strong, but they are inescapably risky.

In UK media, there was a lot of anxiety around the (not-so-) new government’s expected tax raising policies in the upcoming autumn budget. It might be tempting to see the UK Large-Cap index’s -1.5% September returns in that context, but this would be misleading. The fall in UK Large-Cap stocks was pretty much in line with European shares, and not as steep as Japan’s 2.6% fall in sterling terms. Meanwhile, sterling gained through September – even against the euro. This is why global returns were less positive in sterling terms, and it is more a reflection of the differing paths for monetary policy. Markets expect US interest rates to fall more sharply than in the UK, for example.

The UK Large-Cap index’s slide was also related to falling commodity prices (as the index features several large energy and commodities companies), which were 2.1% down in September. Particularly notable was the fall in Brent Crude Oil; the international benchmark dropped 8.7% in sterling terms. This was down to an increased supply outlook. Libya’s production is back online after its fractured government agreed to appoint a new central bank head, and OPEC+ looks set to loosen production quotas. The latter is because Saudi Arabia needs to regain its lost market share.

Of course, the oil price story is complicated by the dramatic escalation of Middle Eastern conflict at the end of September. The war is devastating, and a broader Israel-Iran war would be much worse for the world, but all we can do in these pages is our job: to think about what it might mean for global markets. In that respect, Brent did notably pick up into the start of October, along with a general move down in global stocks. But at the moment, it does not look like the supply disruptions emanating from the war will be enough to counteract the supply-boosting factors mentioned above. It is therefore hard to see sustained upside for oil prices.

Stable – or even lower – oil prices should support global demand, making them a positive for global growth. We wrote last week that we could get a situation where the US starts expanding again, thanks to rate cuts, at the exact moment China kicks off its rebound. The pattern we have seen in recent years has been the world’s two largest economies working on different cycles: growing and slowing at opposite times. If the two now start growing in tandem, that would be very positive for global growth. And, with returns being relatively low since the summer (with pockets of volatility along the way), asset valuations no longer look as stretched as they did earlier in the year. That makes for a good medium-term outlook.

Where do cars go next?

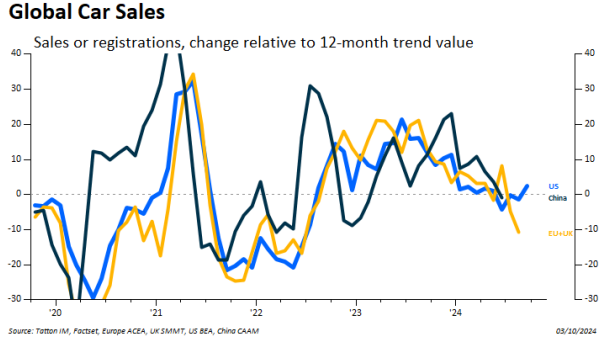

This year was supposed to be a recovery for automotives. At the start of 2024, pandemic-era supply chain disruptions were fading, global interest rates looked set to fall, and capital markets were excited about resurgent global growth. Even Chinese demand looked like it might improve. But, we are now coming to the end of the year and the autos manufacturing sector is in trouble. Stellantis and Aston Martin became the latest European carmakers to issue profit warnings last week, and share prices for the big companies have been hammered.

How did we get here?

Carmakers’ troubles are plentiful, but the biggest single near-term factor is China’s weak domestic growth and overproduction problem. Beijing announced stimulus packages recently that have got markets excited about a Chinese growth rebound, and that caused a bounce in the sector. But its long period of malaise still weighs on autos. Previous Chinese policy tried to stimulate growth by ramping up production, but that resulted in a global oversupply of electric vehicles (EVs) which has held back producer pricing power. The inventory overhang still needs to be worked through.

There are longer-term structural factors at play too. For decades, the autos sector was made up of a handful of major global players that produced relatively similar goods to a strong and stable base of consumer demand. The EV transition has complicated that picture, and investors overwhelmingly expect the future market to look very different to the current one, as cars turn from complex mechanical machines into digital devices on wheels. We see these expectations in current stock prices: Tesla has over 15 times the market capitalisation of Volkswagen – even though Volkswagen makes over three times Tesla’s current revenue.

Global economic fragmentation complicates the outlook even further. The EU’s member states today voted for the imposition of tariffs on Chinese EVs (Germany voted against), and Chinese consumers no longer favour US or European made cars to the extent they once did. European manufacturers (and politicians) are in a particularly tight spot, squeezed between US protectionism and Chinese restructuring. All the while, Europe’s domestic demand is still recovering from the biggest energy price shock in a generation.

Autos drive (large parts of) economies

It is hard to overstate the economic importance of the autos sector. It is estimated to contribute between 3-5% of total global GDP, and carmakers are usually the bellwether for global manufacturing. The industry employs millions across most major global economies. 4.5% of US jobs are in or related to car manufacturing, while 8.3% of EU jobs were related to autos in 2021. The figure was 11% in Germany, and a massive 16% in Slovakia, Europe’s largest national proportion of automotive jobs.

The sector creates many thousands of jobs, which is why politicians are so sensitive to carmakers’ fortunes. Stellantis’ revenue alone was worth nearly 10% of the Netherlands’ total GDP in 2022. The revenue of Germany’s top carmakers was worth nearly 14% of its GDP, while the revenue of Japan’s top carmakers was just under 12% of its GDP. This explains the sector’s particular importance to Europe and Japan – and is one of the reasons growth has been weaker there than in the US.

While the US car industry is huge, it accounts for a smaller proportion of jobs and the economy, compared to Europe. But revenues and jobs are far from the whole story. Car production is a symbol of industrial policy, and the sector’s workers represent a hugely influential constituency. Much of Donald Trump’s early political success was built on appealing to this constituency – which is partly why he (and now President Biden) favour tariffs. Those tariffs are ironically now a headwind for global carmakers, but probably more so in Europe than the US.

A confusing outlook

In spite of automakers’ struggles, you can make a solid case that global demand for autos should see a cyclical rebound. Central banks are cutting interest rates, which should boost demand directly (through lower financing costs) and indirectly (by stimulating growth). China is enacting stimulus, which should boost its demand and help fix the inventory overhang. There is currently an oversupply in the global oil market too, which should bring down fuel prices and incentivise driving.

But every part of that story has its own challenges. The US Federal Reserve, for example, is cutting rates because it is worried about unemployment – and the unemployed usually do not buy cars. Chinese policy has been erratic in recent years and cannot be relied upon to consistently deliver growth – as we have discussed in these pages. Meanwhile, Middle Eastern conflict could easily put a floor under oil prices, certainly if things worsen from here.

Those are just the cyclical factors; the structural case is even harder to untangle. We still do not have a clear picture of what the global autos market will look like in 10 or 20 years. The switch to EVs looks inevitable, but there has already been backsliding on climate policy and new technologies are unpredictable by nature. For us, one of the key questions is: to what extent is EV policy driven by strategic rivalry with China, and to what extent is it driven by long-term climate goals? That question is near impossible to answer before the US election next month. At least until then, carmakers will probably remain under pressure.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.