Published

6th November 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –6th November 2023

Dovishness proves contagious

Just how much change a week can bring to markets was amply visible during the last seven days. Last week we wrote about how negative sentiment in stock markets can turn into a self-perpetuating destructive force for an entire economy as the investing public feels the heat of being poorer (at least on paper). This week, we look back at pretty much a reversal of last week’s perspective after stock markets staged an impressive bounce back. Last week’s rally was still dismissed as an entirely predictable trading-based short-term reversal from oversold levels. However, by the end of the week the bounce has proved far more substantial and persistent than anyone had dared to suggest would be possible or probable last week.

So, what has fundamentally changed? Well, it is not the economic data, where there has been no significant changes from the previous ‘not as bad as expected’ string of releases. What did change though was that – contrary to expectation – the US Federal Reserve (Fed) seemed to adopt a similarly somewhat dovish tone to the European Central Bank (ECB) last week. Why this matters for sentiment is because history has shown that loading up on equity risk at the point of peaking rates and yields has historically been a very good formula for achieving outsized returns, as risk asset markets have staged recovery rallies thereafter.

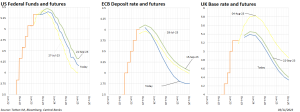

The week’s swing in the perception of central bank policy into 2024 begs the question: Is dovishness contagious? As we reported the previous week, the ECB led the way on 26 October in leaving interest rates unchanged. President Christine Lagarde’s press conference was distinctly dovish, as we noted then, and that already constituted a distinctive change from previous months – albeit not entirely unexpected given how much weaker Europe’s economy has been compared to the US. However, into the beginning of last week, most felt the other central banks would be reluctant to cast aside their hawk costumes.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) announcement last Tuesday appeared to confirm that, when Governor Ueda told us that the 10-year rate would be allowed to go above 1% but leaving its rate at -0.1%. The prospect that yields might be allowed to go higher might seem hawkish, but when the government announced a fiscal package designed to boost growth a day later, it was clear the monetary and fiscal policy mix remains accommodative. As if to validate this conclusion, the Yen traded weakly after the BoJ announcement, a clear indication that investors saw the BoJ move as covert dovishness.

The main event of the last week though was the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) meeting. Few were expecting any interest rate move this month, but a majority of commentators thought another 0.25% move in December likely given next month’s meeting has more research inputs. September’s FOMC meeting yielded no rate change but in the press conference after, Fed Chair Jerome Powell intimated we should expect further tightening. Thereafter, 10-year bond yields moved from below 4.5% to trade above 5% while the S&P 500 fell and credit spreads widened as the ‘higher for longer’ message seemed to at last reach markets’ attention. As a consequence, cost and availability of finance tightened considerably, without central bankers even having to raise rates.

Some members of the FOMC said over the month that this “tightening of financial conditions” was equivalent to a rate rise and hinted this would obviate the need for further rate rises, which set the path for forecasts of no rate rise – at least for this month.

After last Wednesday’s meeting, Powell effectively backed that view, giving the strong impression that the FOMC is becoming convinced their work is done; that the employment market is becoming less heated, wage growth is calming, and inflation is set to come back towards target. It felt like the opposite of the September message and the market reacted accordingly.

In comparison, the Bank of England (BoE) is still in more of a bind. Its Thursday meeting concluded with the same ‘no rate rise’ decision as their US and European counterparts, while the BoE’s statement acknowledged the stress in the UK economy, with interest rates hurting many. Nearer-term measures of inflation in the UK also are helpful at the margin but the BoE’s biggest worry remains and differs in that that measures of wage inflation are still uncomfortably high.

“It’s much too early to be thinking about rate cuts,” Governor Andrew Bailey said in a statement released with the decision. “Higher interest rates are working, and inflation is falling. We need to see inflation continuing to fall all the way to our 2% target. We’ve held rates unchanged this month, but we’ll be watching closely to see if further rate increases are needed.”

It is redolent of Hamlet: “The Governor doth protest too much, methinks” (with apologies to Shakespeare). Investors will be entitled to ask why he is drawing attention to what he is not thinking about. At an Oxford Economics morning conference last week, Michael Saunders, recently departed from the Monetary Policy Committee, mentioned that the BoE sees the average weekly wage data as flawed (the response rates have declined markedly among other problems). Other indicators suggest wage inflation has been slowing to a ‘normal’ pace.

In all but the BoJ’s case, investors took the past two week’s post-committee press conference tone to mean that the central Banks are increasingly of the opinion that rates are now at their peak and that inflation can be brought back towards 2% without the need of a recession. Their work is done, was what markets took away from it.

Even in the BoE’s case, another rate rise is only partially priced in. Most importantly, investors now see US rates on hold before a cut in the second half of 2024.

The BoJ aside, the Fed and the BoE – according to forward pricing of rates by markets (see charts)- would be among the last to begin a retreat from high rates. This week, Brazil cut rates again. Meanwhile, pressure is growing on Central European central banks to cut rates given that their previously high inflation rates are subsiding quickly amid very slow real growth.

Indeed, overall the mix of monetary and fiscal policy globally has already begun to shift to accommodation. The fiscal supports from China announced the previous week, and Japan last week, are substantial and added to investor perceptions that the investment environment may be about to become friendlier.

Of course, much depends on the US. We’ve repeatedly seen that bouts of equity market positivity have supported households and businesses with already strong savings balances. The tight US financial conditions leading up to the FOMC meeting have been loosened in only two days. Following relatively weak US employment figures on Friday, FOMC members have to believe that the easing in the US labour market is more than seasonal if they are to hold on to their new-found dovishness.

What last week’s market moves also suggest is that institutional investors have been short of risk assets, both in equity and bond markets, while private households have been diverting money into their savings rather than investment accounts. This type of rebalancing flow may be ‘short-term’ but it can still go on for some time. Nevertheless, these past week’s market action informs us that the ‘higher for longer’ rates perception that only just sunk in over October may have already reached its expiry date given central bankers’ unexpected dovish tones. It may be way too early for a ‘Santa rally’ but November and December are seasonally bad months for weather but brighter months for investments. It will be nice if things feel less soggy.

October 2023 asset returns review

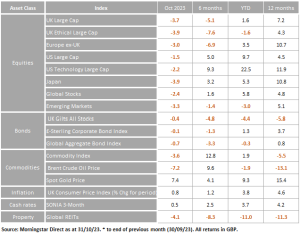

There is no sugar-coating it; October was not a good month for investors. Headline indices sank across every major region and asset class, as global financial and economic conditions finally took in the central bankers’ ‘higher for longer’ mantra and started pricing in what that might mean for asset valuations over the foreseeable future. Economic indicators showed weakness across the developed world, but this was not the ‘good’ kind of bad news that, in the past would have made markets predict more dovish central banker pronouncements.

On the contrary, it finally became consensus that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) would keep interest rates high for the foreseeable future regardless – crushing historically high inflation but bringing asset returns down with it. This has been a slow-motion realisation, considering ‘higher for longer’ is effectively what the Fed and other central banks have been saying for over a year. It has clearly happened now, as last month’s table of returns shows.

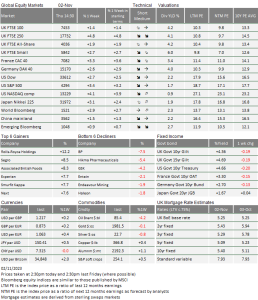

In human terms, the most devastating story of the month was obviously the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war. As horrible as the scenes are for anyone to watch, capital markets are not a moral barometer and so – for better or worse – global asset prices were relatively unmoved in the immediate aftermath of Hamas’ 7 October attrocities and what followed in reaction. In terms of the world economy, markets’ main worry is a broadening of the conflict to the wider Middle East and what this would do to commodity prices. It is perhaps unsurprising that the only meaningful positive returns in October came from gold and cryptocurrencies – so-called safe-haven asset for traditional and digitally-inclined savers. Tellingly, the Swiss franc (a safe-haven currency) rallied too.

Oil prices did spike in the wake of war but have come back down since. Brent crude, the international oil benchmark, closed a peak of over $92 per barrel on 20 October, but finished the month a little over $87 per barrel, a 7.2% fall in sterling terms, despite numerous supply-side pressures. Along with the fighting, OPEC+ (including Russia) has been aggressively cutting production to push up prices. These had previously inflated Brent, leading to some concerns around renewed inflation pressures. As we wrote last month, oil inflation was never likely to create a sustained inflation push, since demand and spending power has weakened dramatically over the last year. Higher energy prices are more likely to act as a tax on consumers and non-energy businesses, hence reining-in activity. October’s petering out of oil’s rally supports this view.

In regional terms, October’s worst performers were the UK and Japan, with sterling returns of -3.7% and – 3.9% respectively. The British economy is clearly seen to be in a weak position and interest rates are biting, evidenced by the news that mortgage approvals sank to their lowest level since January. Interestingly, this coincided with a surprise 0.9% increase in house prices for October which Nationwide attributes to a lack of properties for sale. Thankfully, shop price inflation sank to 5.2% last month, according to the British Retail Consortium. The Bank of England will maintain interest rates at their highest level in decades, though, as policymakers try to crush price pressures which remain elevated despite recent pullbacks as a result of a very tight labour market introducing second round price pressures.

European stocks were not much better off, shedding 3% in sterling terms. Again, the economy is weakening and this is clearly filtering through to inflation data. Headline eurozone inflation fell to 2.9% last month, below economist expectations and the lowest figure for more than two years. It came shortly after the European Central Bank (ECB) opted to keep interest rates static – a break from more than a year of consecutive hikes. ECB President Christine Lagarde nevertheless warned inflation will remain “too high for too long”, repeating the ‘higher for longer’ mantra being pushed by the Fed.

Just like in the US, European bonds have been under immense pressure recently. Borrowing costs for European governments are now the highest they have been since the Eurozone debt crisis of 2011 – when sharply higher bond yields threatened to destroy the single currency. That episode led to an incredible level of central bank support, but the ECB now has the opposite view. If inflation keeps falling – and lower than the 2% target is plausible in the coming months – the policymakers will come under pressure to soften their stance.

Fed Chair Jay Powell has proven himself the master of maintaining a tough stance this year. This is in large part because the US economy has shown a level of resilience that has surprised even the most bullish of investors in 2023. Americans’ willingness and ability to dip into pandemic-era savings – together with the significant fiscal stimulus the CO2 reduction investment subsidies introduced – has kept US businesses going strong and the labour market tight, despite myriad global economic headwinds. Stocks, meanwhile, had been predominantly boosted by the US mega-tech companies and the artificial intelligence investment craze behind them, paired with an enduring optimism that Powell and co will loosen policy sooner rather than later.

Optimism endured no more, it seems. US stocks lost 1.5% in sterling terms in October, while the tech- heavy Nasdaq fell 2.2%. These falls – along with the falls across most major regions – have been almost entirely a response to sharply higher bond yields, whose sell-off has been astonishing in recent months. Long-term US Treasuries touched their highest point in 16 years the previous week, briefly breaking above 5%. Disappointing quarterly earnings for some prominent companies only added fuel to the fire.

These losses should be put into perspective. Not only have they come after the sharpest monetary tightening in a generation across the developed world, but even after the falls, most major equity indices are up year-to-date. Only emerging markets (EM) – battered by weakness in China and adverse global financial conditions – are down among the major regions, losing 3% in sterling terms. With central banks now finally seeing the fruits of their labour, there is a good chance that we are at, or approaching, the real bottom for market sentiment. And if this is the worst of the cycle, it is a pretty mild cycle.

Emerging markets: does growth always mean returns?

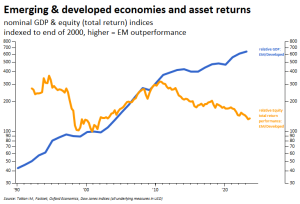

Why would you invest in Emerging Markets (EM)? In a word, growth. As the name suggests, developing economies generally have high potential to develop, and foreign investors are keen to get in on the action. It does not always work out, of course, but that is just part of the game: high risk comes with high reward. We have written a lot about emerging markets in recent months, from the obvious China – whose ‘emerging’ status perhaps stretches the definition somewhat – to India, Brazil and Argentina. The risk-reward profile of EM investment means that for every India or Brazil success story, there are plenty of Argentina- style cautionary tales.

This simple mantra goes some way to explaining why EM assets are generally considered risk-on, doing well when global investors (primarily concentrated in wealthy developed nations) feel confident vice versa. But like any simple mantra, in reality things are a little more complicated. EM assets – certainly those in the benchmark MSCI EM index – have arguably been more affected by weakness in China (whose assets make up around 30% of the index’s total market capitalisation) than monetary tightening in the US and Europe this year. On the other hand, as we noted in recent months, Brazil and India have fared surprisingly well despite weak global growth and tight financial conditions.

Economies and financial markets are, annoyingly, too complicated to fit nice narratives or simple cyclical models. One obvious yet often overlooked complication for EM investors is that there is a world of difference between EM growth and returns on EM assets. China is the clearest example of this. Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) expanded from just over $11 trillion in 2015 to nearly $18 trillion in 2022 – meaning 62.4% growth, according to the World Bank. In that time its benchmark CSI 300 stock index grew just 10%, with plenty of volatility along the way.

For contrast, the US economy grew just under 40% in the same period but delivered 86% equity growth. It is worth pointing out – if only to make the comparison more extreme – that the end of 2022 was a relatively high point for the CSI, and a relative low point for the S&P 500. Chinese stocks have sunk 8% this year, while US companies have added 10% to their share values. This reflects the fact that Chinese companies have faced huge problems – prompting an exodus of western capital. And yet, despite undeniable growth disappointment in the world’s second largest economy, the absolute level of growth has held up okay – certainly compared to the dire performance of Chinese equities.

The discrepancy between the health of the overall economy and the value of domestic assets is a common feature of EMs. Part of the reason for this is that the domestic companies most often featured in national equity indices are not always the biggest beneficiaries of underlying growth. EM funds, like those that track MSCI’s EM index, naturally pick the biggest companies by market cap – usually established (and often at least partly state-owned) firms that are relatively dominant in their respective countries. But these are not high- growth companies over the long-term, which are often much smaller. As in developed markets, periods of growth and dynamism often reward smaller start-ups and disruptors – but these are rarely captured by headline indices.

The feed from growth to asset returns has to go first from the grassroots to company earnings, and then from earnings to share value. EM companies often have problems with both of these links. China and India, for example, have a high prevalence of state-owned and family-owned enterprises in their stock markets. This is something China, with its banking giants and property developers, is famous for, but in India too, the percentage of company shares that are free floating averages around just 40%.

There are often high barriers to foreigners owning shares of these companies at all. And, when they can be owned, EM governments have a tendency to be unpredictable in their private sector interventions – as China has showed over the last few years. On the milder end, this can mean the sudden imposition of higher taxes. On the extreme end, it can be sudden nationalisation or outright bans on profit making (as in the case of the Chinese private education industry). These sudden changes make it hard to evaluate what the risk-reward profile for certain companies even is.

Unpredictability gets at a deeper problem with EM investment: the relative lack of strong corporate governance. For myriad reasons, EM companies are much less geared towards generating profit for public shareholders – whether this be with their internal investment decisions, or the process of actually directing internal cashflow into dividends. In fact, relatively weak corporate governance (compared to developed markets) is one of the key criteria for distinguishing EMs, according to ratings agencies like MSCI and S&P.

Not only are domestic companies often bad at getting asset returns from national growth, but they can often be worse than certain foreign companies. Vodafone, for example, is in the process of selling off underperforming parts of its operation – but is keeping its higher-margin and profitable arm in South Africa. French luxury goods company LVMH, meanwhile, generates a massive amount of its profits in China. As analysts regularly point out, its results are often very sensitive to economic growth in key EMs.

When making the case for EM investment – either in a specific region or in EMs more generally – economists and analysts often point to growth-supportive factors, like weakness in the US dollar or supportive trade conditions. But those factors do not always weigh in favour of EM assets themselves. Indeed, they can often suggest foreign companies with EM exposure. Other asset classes – like corporate or government bonds – can often provide more exposure to EM growth. Growth, on its own, is rarely enough. We will delve into the other factors that matter in the coming weeks.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.