Published

5th August 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

5th August 2024

Central bank week

It’s been another nervy week for investors. Month-end positioning may have had a part to play in creating ups and downs, but most markets were more focused on interest rate decisions. The Bank of England (BoE) cut, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) hiked, and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) stuck. Western central bankers now acknowledge that slower growth needs at least neutral, if not supportive, monetary policy, while Japan is at the opposite end of its cycle.

Equities rallied after the Fed meeting, but Fed chair Jerome Powell’s comments, that he was worried about softening US jobs data, put focus on the labour market. That data came in significantly weaker, with 4.3% unemployment. Stocks ended last week downbeat in response. The much-watched second-quarter earnings from US tech firms were also disappointing, when looking at free cash-flow. On Friday we saw a nasty set from Intel, with the firm indicating a sharp retrenchment and lay-offs of 15,000 employees.

Interestingly, bond prices have started to move up, negatively correlated to equity prices. When this happens, it suggests a weakening in investors’ growth estimates.

Andrew Bailey’s hawkish cut?

Starting close to home, the BoE lowered interest rates for the first time since March 2020 last Thursday, but the decision was hardly emphatic. The bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted to lower benchmark rates from 5.25% to 5% but by the closest margin – a 5-4 vote. Bailey then downplayed any suggestion of a quick journey down in rates.

The governor warned that the MPC must be “careful not to cut rates too much or too quickly”. The BoE’s own forecasts suggest inflation falling below the 2% target within two years, even accounting for more than one rate cut this year (as markets expect). But more hawkish MPC members worry that these forecasts underplay the lasting effects of the inflation shock. Bailey seems at least sympathetic to those concerns.

The MPC no doubt has one eye on emerging fiscal policies from the new Labour government. Bailey downplayed the inflationary impact of last week’s NHS pay rise announcement (wage inflation has long been the BoE’s main fear) and MPC members are likely to see the signals from the treasury as sticking to its fiscal discipline promises. The Chancellor’s warning of a £22bn “black hole” in the budget, and how it might need to be plugged with higher than expected taxes, is a testament to this.

Fed shifts focus to employment.

If the BoE’s move was a hawkish cut, the Fed’s was a dovish stasis. The US central bank held rates steady at its meeting last Wednesday, but chair Jay Powell strongly suggested rates will soon be cut: “A reduction in our policy rate could be on the table as soon as the next meeting in September,” he announced, adding that the committee had a “real discussion” about cutting rates last week.

Powell even suggested that inflation was no longer the Fed’s primary concern. He emphasised the bank’s “dual mandate” to promote both price stability and maximum employment, highlighting that rising unemployment was now becoming a cause for concern. For two years, inflation has dominated policy, and the idea that the Fed would actually be worried about unemployment – rather than welcoming it as a disinflationary force – was far-fetched.

Unemployment metrics have moved close to a ‘tipping point’ (where job losses cause further losses in a spiral). The rise in the US unemployment rate to 4.3% shows soft current conditions, while the ISM Manufacturing Survey data showed a distinctly weak outlook in the sector. Manufacturing tends to lead the much larger service sector, so today’s service ISM data will be important.

So, as mentioned above, bond yields moved down through last week – almost as though Powell’s dovish tones were a de facto rate cut. The 10-year yield moved below 4% and money market futures now have the prospect of multiple rate cuts as more likely than they did a week ago.

Yen strength a cause of rotation

On the same day the Fed pencilled in an upcoming cut, the BoJ raised rates for the second time this year. The new 0.25% benchmark is the highest Japanese rates have been in 15 years, and it signals that the BoJ is in a genuine rate-hiking cycle. That pushed the yen below ¥150 on the dollar for the first time since March, which had impacts on the domestic and foreign equity markets.

Firstly, domestic investors seemed spooked by Japan’s potentially slowing growth, after some weak signs. International investors benefitted from the surging yen early last week, but Japan’s Nikkei 225 fell over 5% during Friday trading. Even with the currency benefit, Japanese stocks are the regional underperformer, falling more than 3%.

Secondly, we think yen strength has impacted US markets substantially. The yen had been consistently sliding all year, and was above ¥161 to the dollar as recently as the second week of July. Its strengthening since then has coincided with a stock market rotation away from US mega-caps, and that is no coincidence. In our round-up of July returns below, we note how leveraged institutional investors (i.e. hedge funds) have had large buy positions on US tech, and sell positions on mid-cap or non-US stocks. Loose Japanese borrowing conditions and a weakening yen have been an important source of funding for that trade, thanks to the chasm between US and Japanese rates.

The BoJ is now tightening while the Fed is loosening, so that source of funding will inevitably diminish. We suspect this was a trigger for the move out of US mega-caps and the sharply stronger yen. The question now is whether the trend of the last few weeks can continue. Market moves that are caused by the positioning of certain key players can often run out of steam – simply because those positions get evened out. There are reasons to think that might have already happened, such as the notable underperformance of small caps this week.

The wrap

If stocks – especially small caps – are to benefit from here, the Fed will need to pull off a ‘soft landing’ (inflation falls without damaging profits or employment too much). That is still the most likely outcome but, as Jerome Powell warned his fellow FOMC members, US employment is more fragile than it previously looked. We should hope the Fed has not missed its best time to cut.

If economic data worsens further before September’s meetings, the bond markets will discount further rate cuts before the Central banks can enact them. Lower yields should be enough to make equity valuations more attractive, and lower interest costs should spur growth. But US valuations are already high – based on optimistic earnings outlooks that are already somewhat challenged. Some Q2 results are not looking so stellar, and Intel’s massively disappointing numbers today don’t help. Yields would have to fall sharply to make those valuations look reasonable, so markets could struggle in the short-term.

This sort of turbulence is very normal. A pullback from the equity market highs is always to be expected and trying to call the highs or lows is usually a losing game. It is, as ever, time in the market – not timing the market. Perhaps we should enjoy our holidays instead.

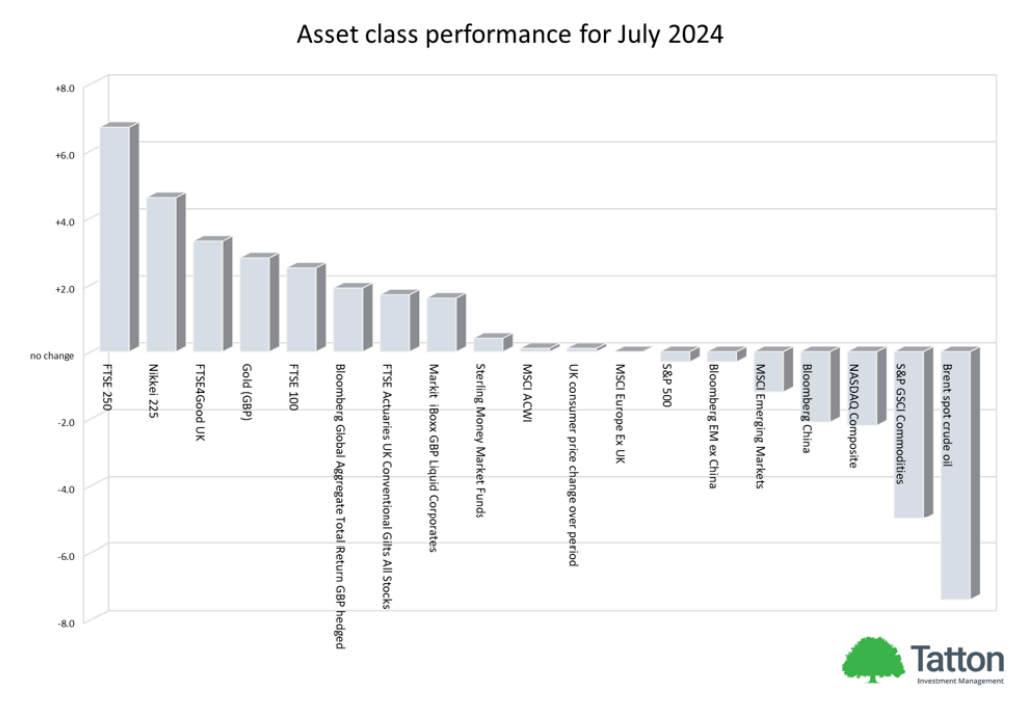

July 2024 asset returns review

July was a dramatic month in capital markets. Huge political events were scattered throughout the month, starting with an electoral landslide for the new Labour government here, and ending with renewed IsraelIran tensions. In between these were the attempted assassination of former US president Donald Trump, and President Biden’s decision to drop out of November’s election. These events formed the backdrop for a stock market realignment: the previously dominant US mega-tech stocks lost, while smaller-caps and equities outside the US gained. The irony is that, after all these twists and turns, the global stock index level ended almost exactly where it was a month ago in sterling terms. The table below shows major index returns in full.

A weaker-than-expected US inflation figure incited the change. It bolstered market expectations of September rate cut from the Federal Reserve – a cut chairman Jay Powell all but confirmed at the US central bank’s end-of-month meeting – which will relieve borrowing costs for smaller companies. US small caps were further boosted by the assassination attempt on Donald Trump, as markets assumed the Republican candidate would win a second presidency and enact his tax cut agenda.

Election predictions were then complicated by Joe Biden stepping aside and Vice President Kamala Harris becoming the presumptive Democratic nominee (though Trump remains the betting markets’ favourite) and the Russell 2000 has been flat over the last two weeks. But the Magnificent 7 continued to struggle and, given those companies’ outsized influence in the US stock market, the S&P 500 ended July 0.4% down in sterling terms.

The role reversal represented a shift in the momentum trade. Before July, there was significant positioning among leveraged institutional investors (namely, hedge funds) in favour of US mega-caps and against small caps and non-US stocks. Bit by bit, the month’s major events chipped away at the rationale for this trade. Volatility shot up – particularly for US tech stocks, recording 28.5% annualised in July – which forced hedge funds to reduce their positions. These dynamics are similar to a “short squeeze”, which in this case helped small caps and hurt the Magnificent 7.

The strength of Japan’s currency contributed to these moves. Yen weakness was a mainstay for the first half of the year, maintained by the Bank of Japan’s loose monetary policy. We have said for some time that the yen looked oversold, considering improvements in Japanese corporate structures and the inevitable tightening of the US-Japan rate gap. Sure enough, on the last day of July, the Bank of Japan raised rates for a second time this year, and the Fed strongly signalled a cut.

From the beginning to the end of July, the yen went from above ¥160 on the dollar to below ¥150. That removed a cheap source of funding for the hedge fund types noted above (further undermining the longMagnificent 7 trade) and it also increased the value of Japanese stocks for international investors. Japan was the best performing large-cap index through July in sterling terms, and it is second only to the US year-todate.

Japan was not top of the class when you include small-cap indices, though. That honour goes to the UK, whose UK Mid-Cap index jumped over 6% through July. The UK Mid-Cap index is a much better reflection of UK economic expectations than the multinational-focused UK Large-Cap index, so this move is a welcome vote of confidence by international investors. Growth and business confidence have been improving, and through July markets had priced in the Bank of England’s decision to cut rates (which eventually came on 1 August).

Optimism is clearly also down to the new government. Labour’s victory at the start of the month was fully expected, so stocks did not move much in immediate response. But Downing Street’s actions since – promises on housebuilding, fiscal discipline and (particularly) improved relations with the EU – have been well received by markets. Sterling strength dissipated as the month went on, but it is a good sign that this did not knock stock market momentum. UK assets have been unloved by international investors for many years, and we would welcome any change on that front.

Finally, the weakest region was China, whose growth disappointed once again. International investors were underwhelmed by the communist party’s third plenum – an economic planning forum held last month – as no significant economic supports were announced. China’s sluggish economy is one of the reasons commodities, particularly iron and steel, have been so weak. Domestic demand is still weak in the world’s second largest economy, which is a disinflationary force for the global economy.

Overall, July was a shakeout for many institutional investors, and that left global stocks flat in sterling terms (though dollar returns were positive). But, we think the rotation away from dominant mega-caps is a good thing for the future. Overall portfolio returns are still decent, and growth prospects are much broader based.

DISCLAIMER

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.