Published

4th December 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 4th December 2023

Price shock reversal

November brought investors the opposite of October and turned most portfolio returns into positive mid- single-digit numbers for the year.

As we have written here over the past weeks, the distinct turn in sentiment that drove markets in November was, once again, mostly about central banks and the likely path of interest rates. After October was about ‘higher for longer’, early November transitioned to ‘no more rate rises and the next move is down’, when inflation came down far more than most had expected. Last week, we heard discussions of Eurozone rate cuts in time for Easter.

This followed the release of provisional European inflation data for November that surprised on the low side for the third month running. Overall consumer price inflation came in at a just 2.4% year-on-year rise in November, less than half its pace as recently as August. We take a deeper look at the global state of the fight against inflation in an article below, with a specific focus on what may or may not be different in the UK by comparison.

Markets now fully discount a European Central Bank (ECB) rate cut in April and economists are catching up with this view after penning their 2024 outlook reports as far back as October. Admittedly, most ECB participants are yet to say they agree even after last Thursday’s data.

In the US, even though inflation there is still between 3% and 4%, some central bankers are validating these ‘next move is down – earlier than thought’ expectations. US Federal Reserve (Fed) member Christopher Waller is noted for similar views to those of Fed Chair Jay Powell, so markets reacted quickly when he said diminishing inflation would naturally allow the Fed to cut rates. Clearly, it is no longer too early to talk of cuts.

Looking at the source of the changing inflation picture, by far the weakest area of pricing power is now in goods and energy. While rate setters tend to ignore short-term moves in energy prices, the experience of 2022 showed that a price shock precisely in those areas can have significant second-round impacts on more ‘core’ goods and services. A shock can be a rise but it can also be a fall, so the current fall in oil prices is worth having a look at.

OPEC+ finally met last week in a videoconference, having delayed the session from the previous week. A cut in production was rumoured and a cut of 900,000 barrels per day (bpd) was announced. A statement on the OPEC+ website said Russia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait and Iraq made a “voluntary” pledge while Saudi Arabia would continue its unilateral one million bpd cut until April next year.

Despite these supply cuts, oil prices fell back to the previous week’s lows and so it appears that OPEC+ is losing its grip of the supply side. The group is defined by a shared reliance on fossil fuel revenues so one might think they all want to maximise oil prices. However, they have differing timescales for when they need the revenues and that disparity is heightening the internal competition for current sales. The dramatically strong global growth seen in the post-COVID bounce in 2022 made for an ideal environment to squeeze supply. Demand was huge and immediate; supply could be squeezed for a few weeks resulting in historically high oil prices.

This year has seen more normal levels of economic growth and demand remained at fairly solid levels through the summer and into early autumn. However, signs are that growth slipped during October and November. It’s not disastrous by any means, but a return to pre-COVID normality is on the cards and the resulting slow energy demand growth is probably not strong enough for some of the OPEC+ members.

Most of the problems for OPEC+ are driven by potential global oversupply. Supply from outside OPEC+ is increasing. US production had a notable boost recently after shale gas extraction increased again lifted by the higher price levels. New fields are opening in in Brazil (which has been invited to join OPEC+). They produced 3 million bpd last year and are targeting 5.4 million bpd by the end of the decade – a level of output which would see them rise from the 9th largest oil producer to the 4th. Guyana’s production is also increasing sharply. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia is trying to bring Iran back into the fold as well. Iran is talking about production rising to 4 million bpd next year, a level they’ve not approached in 20 years.

Even within OPEC+, supply is increasing, although perhaps quietly. While the main middle-eastern producers have become long-term in their outlook – despite shortfalls in government finances –Russia has become absolutely reliant on cashflow. Last week, it was announced that Putin had signed the 2024-2026 budget which returns Russia to its late Communist-era levels of defence spending. It has limited access to funds other than through the sale of fossil fuels. Thus, it has to keep revenues up by selling as much as it can at the price available. Its commitment to a cut is necessarily voluntary and always short-term. It is notable that natural gas pipeline flows through Ukraine have not changed in recent months.

Most oil analysts do not see faltering demand as a major issue and most were predicting mild oil price increases. However, the fall back in oil prices has occurred in the past few weeks amid signals of slower industrial output. In particular, China continues to look weak and that position has continued for far longer than we anticipated. As mentioned the previous week, we could be at quite a critical juncture for global growth, given the lack in demand from China and elsewhere seems to be leading to an extended inventory drawdown that delays new orders. While global manufacturing sentiment indices such as the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) surveys are not deteriorating greatly, they are yet to signal a return to growth. The venerable US Institute of Supply Management’s manufacturing index is one of the longest and most respected of economic indicators, and that remained at 46.7 (a sub-50 reading indicates a contraction), disappointing consensus expectations of a small rise.

Service sector PMIs, which are demonstrably more important for employment and remained expansionary, have been slowly deteriorating since the summer. The announcements of layoffs by banks such as Barclays signal that big companies may be increasingly trying to defend margins. As we head into the New Year, it will be important for economies and wider corporate profits that we don’t swing into a faster round of service sector cost-cutting.

The fall back in energy prices might signal growth worries, but lower energy prices are at the same time a growth spur for the wider economy. The right price is one which stabilises the supply/demand balance, and we should be grateful we are in a period where prices are moving gradually and bearably. This suggests that while we may be experiencing weaker growth now, the likelihood is that costs will be cut naturally and we are in the final stages of a welcome return to normality.

UK inflation exceptionalism

The Bank of England (BoE) continues its expectation management programme. Since the previous Friday, two top officials and one external member of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) warned us not to not get excited about looser monetary policy, sticking firmly to the ‘higher for longer’ mantra on interest rates.

Last Tuesday, Jonathan Haskel, an external member of the MPC, told a Warwick University crowd there was no scope to cut interest rates from 5.25% “anytime soon”. His message to markets was unequivocal, saying rates will “have to be held higher and longer than many seem to be expecting”. It comes after a similar warning from BoE Chief Economist Huw Pill last Friday, and from Governor Andrew Bailey before that.

Last Thursday, external member Megan Green said “There is not only a risk of weaker activity than expected. There’s also a risk of stronger activity than expected and so that’s why I continue to put my focus on inflation persistence”.

UK inflation, like everywhere in the developed world, has fallen rapidly in recent months, sinking to 4.6% in October – the lowest level since 2021. Economic growth is weak while input costs are down quite sharply in some major sectors, removing significant price pressures from the economy. But Britain’s monetary policymakers keep pushing the line that price pressures are dangerously high and will need tight containment measures for the foreseeable future, perhaps partly because growth in worker productivity is showing no signs of picking up.

The MPC’s current expectation management exercise began when Huw Pill made an apparent misstep earlier this month by announcing markets were being reasonable in expecting a rate cut some time in the middle of next year. Backpedalling since has not reversed rate-cut expectations though, and 10-year government bond yields are currently at 4%, the lowest level since May.

Britain’s bond markets have largely moved in line with developed world trends this year, and the latest fall in yields is no exception. According to the BoE, though, drawing inferences from global economic conditions might not be appropriate. In the bid to pour cold water on rate cut hopes, the BoE’s Deputy Governor Dave Ramsden warned last week that UK inflation is becoming more “home-grown”. Ramsden repeated the messaging that wage growth was driving UK-specific price pressures. That is why, despite the fallback in energy and other input prices globally, Britain’s inflation “is going to be really difficult to squeeze out of the system”.

The BoE and other economists worry that Britain’s supply side problems may stem from a combination of pandemic hangovers and Brexit frictions. We imposed extra costs on goods and labour relative to our largest trading partner just before the global economy entered an unprecedented period of supply bottlenecks. In this light, UK-specific inflation pressures are unsurprising – as is the BoE’s focus on wage growth from a structurally tighter labour market.

Ramsden pointed to services inflation – favoured by central banks as a more accurate read-through of labour conditions – remaining uncomfortably high as a sign of Britain’s stress. The services component of the consumer prices index (CPI) was “actually much stickier and higher than we were expecting at 6.6%”. This shows, in the MPC’s view, why UK interest rates must remain elevated.

Some investors have seen this as arguing that the UK has a greater structural inflation problem than other nations. We’re not so sure. Other countries are experiencing a very similar dynamic. The JP Morgan (JPM) global inflation monitor for October showed there is a growing divergence between goods and services prices across all major developed economies. While goods prices have settled – and even fallen in some cases – services inflation remains “uncomfortably high” across the developed world.

JPM analysts attribute a huge part of fall in goods inflation – and hence in falling headline inflation figures – to declines in consumer energy prices feeding through the value chains of production. This matches Ramsden’s rhetoric, who highlights “a bigger fall in the energy component than we were expecting”, but similar declines can be seen in the US, Canada and the Eurozone. Along with the UK, these regions saw the sharpest energy price declines, averaging -2% in October according to JPM.

JPM’s measure of global services inflation for October was an annualised rate of 4.2%, which researchers said was “fairly uniform across regions, reflecting still tight labour markets”. This suggests that Britain’s sticky services inflation is the same for everyone, but even if increases were significantly sharper here than elsewhere – contrary to JPM’s analysis – the underlying problem rationale seems to be the same. Indeed, JPM analysts point out that measures of sticky US inflation have reaccelerated in recent months.

Of course, the fact we have the same problems as everyone else says nothing about how to solve them. Tight labour markets – which JPM suggests are ubiquitous – would suggest that interest rates indeed need to remain high. But one could actually argue this is a bigger problem for the US, where growth has stayed strong thanks to a seemingly unshakeable American consumer. This is in stark difference to the UK, where sentiment among both consumers and businesses has been dour. Indeed, despite the BoE’s laser focus on wage growth, for most of the last year headline wage growth figures have been below headline inflation – meaning cuts in real terms.

And yet, the Federal Reserve (Fed) is the central bank seemingly relaxed about markets pricing in rate cuts, while the BoE scrambles to quell those expectations. There could be many reasons for this discrepancy – not least that the BoE has looked structurally more hawkish than counterparts in the past two years. But we suspect that it is at least partly talk. The MPC knows the effect of longer-term rates (often tied to mortgages) on the fragile UK economy and is likely trying to persuade where it cannot directly control. After all, expectation management is as much a part of monetary policy as interest rates.

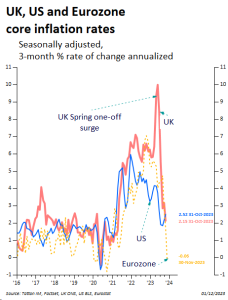

A final note: the UK core inflation rate (ex food and energy) has been higher than both the US and Europe since about mid-2021. Over the longer term, UK has averaged about 0.4% per year more than the Eurozone experience. However, this is not the case relative to the US. Since the end of the 1980s, UK core inflation has averaged about 0.2% per year less, even when taking into account the recent surge. We experienced a sudden price surge during this spring, which appears to have been a one-off and not experienced elsewhere (see chart). Importantly, this surge is still in the year-on-year rate but, when we look at the quarter-on-quarter rate, UK core inflation is now below the US rate and looks like it will remain similar or lower, especially given recent sterling strength.

It would seem that UK investors periodically become convinced of national inflation exceptionalism and yet the evidence is that we are no more susceptible than the US. As a result of what we have observed and laid out above we expect that the UK inflation narrative may well change as we head into 2024.

Wind of change for renewables?

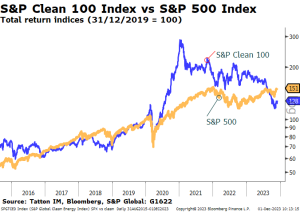

It has been a miserable year for investors in the renewable energy sector. Tighter oil supplies have pushed up the price of fossil fuels, increasing the short-term returns on oil and gas stocks. When you add in the tightest global monetary conditions in decades – which have hammered valuations for all long-duration assets – it is a recipe for disaster, since clean energy stocks are seen as longer-term investments. The S&P Global Clean Energy Index has fallen over 30% year-to-date.

What makes things worse for companies is that the industry has been unloved for some time. S&P’s Clean Energy Index achieved dizzying heights at the start of 2021, thanks to sharply rising energy costs and an expected political drive for the global green transition. But shifting macroeconomic factors pushed fossil fuel companies ahead, with clean stocks losing nearly 60% from the January 2021 peak. The chart below shows the Clean Index (comprising 100 global companies involved in renewable energy) relative to the US S&P 500 large cap index, both in total return index terms:

Such a prolonged downturn has starved renewables of much-needed investment – particularly damaging for capital-intensive projects like building wind and solar farms.

Earlier this month, the world’s biggest offshore wind developer Ørsted abandoned two massive projects off the coast of New Jersey, costing the company £3.3 billion in impairments. Shares tumbled and Ørsted’s two most senior executives lost their jobs in the aftermath. Investors were told there was little choice thanks to sharply higher costs – both in terms of financing and materials.

Project cancellations or modifications are happening everywhere you look across the industry. Swedish developer Vattenfall recently scrapped plans for a massive windfarm off Britain’s Norfolk coast, though is thinking of resubmitting it after the UK government indicated it may improve the terms of the bid. Siemens Energy AG has had to look for €15 billion of guarantees from the German government (although admittedly faulty wind turbines at its Spanish arm Gamesa played a role). Even Canadian battery recycling company Li- Cycle had to pause a development thanks to new cost estimates being nearly double its budget. Profitability and balance sheet concerns are at the root of all of them.

The strangest thing about the industry’s malaise is how simple it is. Problems are easily explained by a standard cyclical argument: big infrastructure projects are inherently long-term investments, and the current value of long-term investments decreases when current costs are high and the growth outlook is weak. Indeed there has been weakness across most assets linked to infrastructure projects this year and, since most of renewables’ perceived investment value is linked to such building projects, the dearth of capital makes sense. In particular, losing out to preexisting oil and gas drillers – with low ongoing costs and high sales prices – makes complete sense.

And yet, if it were that simple, solutions would be easy. Not for companies themselves of course, but for policymakers who have repeatedly professed commitments to the green energy transition. The solution – as energy analysts have argued for years – would be to properly align incentives so that short-term cyclical forces do not outweigh the longer-term transitional needs. But doing so would require political sacrifices that are hard to sell – both temporal (giving up prosperity now for sustainability later) and distributional (giving up individual or national prosperity for the global good). As Mads Nipper lamented before he left as Ørsted chief, “This industry does not need to be in a crisis”.

We have seen at least some progress on this front recently. A few weeks ago, the UK government promised to raise support for offshore windfarms by 66% in an attempt to draw investment back to the sector. And even with so many projects being cancelled, development of a massive windfarm off the coast of New York – crucial to the hopes of delivering clean energy to northeastern states – are going ahead and seem to already be motivating US politicians to commit more. In spite of everything, this year is sure to see the most clean energy developments on record – with 500 gigawatts of capacity expected to be added according to the International Energy Agency.

It has helped shift the mood too that the green shoots of a cyclical recovery are pushing through. Thanks to inflation figures finally coming down to manageable levels, clean energy developers are finding it easier to work through extensive backlogs. One such company is Vestas Wind Systems, which reported earlier this month that a greater volume of new orders and stronger pricing had helped it become profitable again. Costs are expected to drop sooner for solar energy providers, whose capacity is easier to extend than large wind turbines. Indeed, solar panels are easier commodified than extremely big offshore wind turbines.

These factors have helped change investor perceptions, with the S&P Clean Index rising more than 7% in November. But cyclical moves can only do so much, particularly with markets and the underlying global economy in such a delicate position. For sentiment to swing back around fully, markets need to feel drive to longer-term structural change. The results of the UN COP28 summit will therefore be vital, but rumours that host nation United Arab Emirates plans to use the venue to promote deals for its national oil and gas companies are less than encouraging.

At the 2021 COP26 summit, the political will to change was palpable in a way that summits since have not lived up to. A massive part of that is surely the changing geopolitical landscape around energy markets – and the re-evaluation of national energy priorities it prompted. It is telling that the Chief Executive of clean energy provider AES recently chose to direct his ire at investors rather than policymakers – saying that those selling clean stocks for oil shares are not on “the right side of history”. Even if he convinces some investors to buy into the renewables story, it will make little difference if politicians are not willing to join in.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.