Published

3rd June 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –3rd June 2024

Consolidation

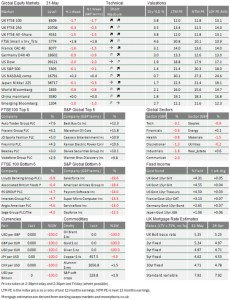

Capital markets were in a dreary mood again last week, with global stocks generally ending the week down between 0.5 and 1%. That almost exactly tracks US stocks, with the S&P 500 losing just under 0.3% through the week. UK equities fared a little worse by comparison, down 0.8% but with a slight pickup into Friday that made the week’s losses milder. There was no obvious trigger to these falls, and little sign of wider market stress. As such, considering the previous monthly and year-to-date gains for investors, last week’s action felt more like consolidation through month end rebalancing, following various indices hitting new alltime highs in May. Looked at in that light, the backdrop looks more reassuring than worrying for long-term investors: previous returns seem to be solidifying, and against improving earnings outlooks, stock valuations look less stretched than they did earlier in the year. That bodes well.

Trump trials but no market tribulations

It may sound odd to say there was no obvious cause of market losses just after Donald Trump became a convicted felon. He once again made history by being the first former US president to be convicted of a crime, after a New York jury found him guilty on 34 counts in the “hush money” trial. But Trump’s legal troubles have never had that big an impact on US stocks, let alone global markets, and that did not change last week – with the bigger chunk of the S&P’s falls coming before Thursday night’s verdict.

Currently, the trial’s conclusion looks unlikely to have any impact on Trump’s chances in the electoral rematch with President Biden. Most Republican supporters are unwavering and consider all the former president’s legal cases to be political persecution, while Democrats already considered him a criminal. The “hush money” case is seen as highly unlikely to result in prison time for Trump, and the more serious cases – for attempting to overturn the 2020 election and mishandling secret documents – are unlikely to be resolved before November. Still, it could have an impact in key swing states, where a less vocal but electiondeciding middle of society could be put off by a criminal running for the US Presidency.

That is not to say US politics has no impact on its economy – far from it. As we wrote last week, Americans’ perceptions of the US economy are dramatically more negative than the real economic data, and one of the key reasons is that political allegiance (i.e. “is my preferred president in office?”) has a massive impact on economic confidence and inflation expectations. Despite unemployment being at historic lows, nearly half of Americans think unemployment is at its highest in 50 years, according to a recent Harris poll.

These perceptions are bizarre when compared to the strength of the US economy – particularly because resilient US consumers have been the key drivers of this lasting strength. Recent consumer confidence numbers have been lower, and it is possible that this could disrupt the US growth story as we get closer to the election. Or, more likely, it could just gently slow the economy, as emotions expressed through surveys and actual behaviours seem to have diverged of late. With the election outcome still too close to call, though, market attention will remain firmly on the interest rate setting US Federal Reserve (Fed).

Increasing realism about rates

Thankfully, expectations about Fed policy have stabilised in recent weeks. There was an outsized move in markets’ implied rate expectations in the first three months of the year, when persistent growth and sticky US inflation pushed the timeline for rate cuts further away, and short-term bond markets priced in greatly fewer cuts for 2024 overall. Those expectations have not moved much recently, though, in line with the fact that US growth, consumer confidence and inflation data have all softened.

Bonds markets suggest the Fed will cut rates just once, by 25 basis points, by the end of this year. More importantly, markets seem to have accepted that this is a fair level for an economy which is gently slowing, but remains fundamentally strong. As shown by recent corporate earnings reports, the benefit of this prolonged strength is profit – from which equities ultimately derive their value. As we wrote last week, the result is a fairly healthy system of checks and balances on markets, allowing them to grow without overheating and threatening a damaging correction.

Interestingly, while the US is gently decelerating, Europe seems to be gently accelerating. Eurozone inflation came in above forecast in May and higher than the previous month, with headline and core numbers picking up to 2.6% and 2.9%, respectively. Markets do not think this will deter the European Central Bank from cutting rates at its meeting this month, but bets for further cuts have been scaled back.

No obvious exuberance in markets

European stocks were a little choppy after the inflation print, but did not fall dramatically. That is a good sign, and again suggests that markets are tuned in to the growth benefits that usually come with inflation, rather than just worrying about interest rates.

Backing this up is the fact that the stocks that were previously the big winners – and particularly those that seemed to have become overextended – were the worst performers last week. On Thursday, shares in Salesforce (US) fell 20% after the company disappointed earnings expectations for the first quarter. Profit growth was $9.13 billion, against expectations of $9.17bn, but what gave the stock its worst day in 20 years was not this small miss, but investors’ realisation that the company is no lower growing at 20% annually but just (!) 10% now.

That speaks to a harsh investor reaction, but it also tells us that markets are laser focused on profits and fundamentals. Only companies who can prove they have significant and sustainable earnings potential are being rewarded with above average valuations. That is good news, considering that, earlier in the year, the main fears were about whether markets had become overexcited and stretched equity valuations into bubble territory. Clearly, markets are still very discerning and that bodes well for sustainable returns. With the growth outlook firming up and a more realistic outlook for rates (with cuts delayed or reduced) we seem to have returned to a goldilocks environment of not too hot and not too cold, just right. Last week seemed a more dreary end to a decent month than feels justified, but the message is positive: returns are based on fundamentals, and the fundamentals are improving.

ESG out of fashion?

ESG investing – where investors factor in Environmental, Social and Governance factors alongside standard risk and returns – was one of the financial sector’s biggest growth areas just before, and during, the COVID19 pandemic. Recent backlashes and periods of underperformance have hit the sector, though. One of the reasons for the style’s underperformance was a strong period for oil and gas companies in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which ESG investment portfolios typically exclude. The other was weakness for Growth as an investing style during 2022, as a result of rising yields. High yields reduce valuations of earnings in the more distant future – which is the typical earnings profile for many of the companies ESG investors favour, like those developing sustainable technologies for the future.

Political controversy was another blow. This falls broadly into two categories: in the US, right-wing lawmakers and press accuse ESG investors of corporate ‘wokeness’ and have initiated legislation to ban corporations’ ESG proposals, while in Europe, the fear of ‘greenwashing’ has turned many away from products that misrepresent their sustainability credentials.

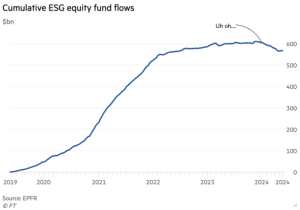

Both the performance and reputational issues are clear in recent media coverage. The Financial Times reported recently that ESG equity funds have had $38.5 billion of cumulative outflows this year. Not only is this ESG’s first period of net outflow, but it comes amid a positive period for equity funds generally. Those not labelled ESG have seen $216bn net inflows this year.

Then there is the shareholder drama at ExxonMobil, which held its annual general meeting last Wednesday. A while ago, activist investor groups tried to bring a non-binding resolution which would commit Exxon to reducing its emissions, after similar resolutions had failed. Instead of going to the regulator to get the repeat proposal excluded (as standard) Exxon tried to take the activist investors to court. Many of Exxon’s other investors are furious about the apparent assault on shareholder rights.

The episode shows the risks that can come from ‘investing for the better’, but it also shows shifting corporate and policymaker attitudes to ESG. Exxon’s activist investors were ultimately small fry that, however noble their intentions, were never likely to materially change one of the world’s biggest oil companies. But, Exxon’s attack has garnered the activists’ sympathy from large institutional investors that might not have otherwise agreed – bringing the climate proposal to greater attention.

The extreme political backlash against ESG is unique to the US’ right wing, but on this side of the Atlantic the concerns are much more around ‘greenwashing’ (products being mislabelled as environmentally friendly) and the opacity of certain ESG investment products. New regulations in the UK and EU are designed to combat these problems by introducing stricter labels for investment products – in particular, dictating which funds or products can use the word “sustainable” and aligning this with the EU’s climate taxonomy.

We believe that these labelling regimes should help make the ESG investment world more transparent. The old rules, for example, did not distinguish between activist funds that try to improve a ‘bad’ company’s environmental or social principles (like Exxon’s activist shareholders) and funds that simply screen off bad companies altogether. This helps end-investors know what they are getting into, and it helps funds and companies by giving clear guidelines they know they have to stick to in order to use certain labels.

Unfortunately, there is still a long way to go in making ESG labels or investments more transparent. One of the best examples of this is ESG ratings metrics: aggregate scores assigned to companies by ratings agencies, usually as a weighted average of how they fare on a host of environmental, social and governance issues that the raters deem to be the most relevant. There are now hundreds of ESG ratings systems, and the more reputable ones get used for selection of various funds or indices.

The ratings systems are typically incredibly thorough and mathematically sophisticated, but underneath the formulas are a network of judgement calls that go into setting which E, S or G factors are more important than others. The fact these are just presented as a single number means bad practices can be hidden under good practices in other areas – like a company that mistreats its employees but uses renewable energy, and hence has a neutral or high ESG rating overall.

More fundamentally, the justification for these judgement calls is usually not transparent. That is a problem, because without knowing why certain companies are judged as ‘better’ on ESG metrics, we cannot know whether we actually agree with that judgement – and hence the company’s inclusion or exclusion from our investments.

In a sense, these problems naturally arise from the fact that people often disagree about what counts as morally good, and the topics they disagree on are exactly the ones relevant to ESG investing. But, that also shows why transparency is so important: these are high stakes issues that people often feel very strongly about, so those providing investment advice or products have a responsibility to be upfront and let people decide for themselves.

In that respect, the fact regulations are being brought in to address the transparency issue is a sign that ESG investment is still hugely important, even if the sector has fallen on hard times. According to all the survey data, the demand is still there; investors are just worried they might not get what they want. New regulations, and shifting corporate attitudes towards sustainability in general, will hopefully soothe some of those fears. Part of maturing as a sector is moving away from being fashionable towards being a key part of a wider ecosystem. As that happens for ESG investments, the transparency and reliability issues are crucial.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.