Published

2nd September 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

Balancing acts

Last week was a flat week for global stock values, but with a fair amount of dispersion. US returns were once again weighed down by tech, but the UK and Europe were up over 1% on Friday. The overall sluggish picture seems a strange reaction to supportive comments from US Federal Reserve chair Powell and a healthier than expected US economy, but markets are chewing on a few things.

UK investors suspect a hike in Capital Gains Tax (CGT), possibly among other measures, in the government’s autumn budget. Anecdotal evidence suggests this is keeping advisers very busy – and some have predicted UK market consternation.

There was certainly no sign of that in UK stock values. We have argued before that readily available CGT investment wrappers mitigate CGT changes. Underlying fundamentals are more important, and those probably will not be greatly affected by the budget. We will of course keep an eye on this, but return for now to some more globally impactful news.

Markets seem to be more like their pre-pandemic selves, after many ups and downs. It’s difficult to distinguish the permanent changes from the reactionary ones, but many strongly impacted areas are now more than fully recovered – evidenced by the travel industry’s new high in air miles. Interest rates and bond yields, however, are more like where they were before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). We think a return to pre-pandemic levels, rather than pre-GFC, is more likely. Yields are likely to go down, even though they were up last week.

A doubling of profits isn’t enough to bring in new Nvidia investors

Ahead of AI market leader Nvidia’s earnings, commentators heralded that the chipmaker’s results are as important to markets as major economic data. In the event, Nvidia announced $30 billion in revenue in the three months to August – up 122% from a year earlier – and expects $32.5bn for the third quarter. Shares in the company then dropped 6% last Thursday, despite beating analyst expectations.

Disappointment may have stemmed from the fact it was Nvidia’s smallest revenue surprise in six quarters. Investors are so accustomed to its freakishly good results that very good is not enough. This is less about the company itself and more a realisation that AI-related investments may have run a little too hot.

We note that last Wednesday’s news regarding Super Micro Computer (SMC) had already set the scene. SMC has been central in the AI stock theme: it went from a market capitalisation of $4bn in January 2023 to $66bn in mid-March this year. As of last Thursday night’s close, it was back to $26.2bn.

For Nvidia, SMC has been a major buyer of the H100, the current flagship GPU chip. According to Bloomberg analysis, SMC was Nvidia’s third largest customer over the past year, forming 8.6% of revenue.

SMC’s shares dropped 19%, after being targeted by infamous short-seller Hindenburg Research. Hindenburg alleges that SMC manipulated its accounts. These allegations seriously damage the optimism needed to invest in long-term themes. The timing was awful for Nvidia, meaning good results weren’t enough and new buyers want a cheaper stock price.

Thankfully, the S&P 500 did not follow Nvidia’s lead. It ended last Thursday slightly down but started brightly, thanks to some positive economic data. This is a decent sign – suggesting faith in the broad economy even if mega-cap valuations are a little stretched.

After the central bankers’ Jackson Hole conference recently, markets are more focused on what central banks do. The key question right now is…

Are interest rates currently restrictive?

In his speech recently, Fed chair Jay Powell reemphasised a focus on employment, more than inflation. Subsequently, bets on a 0.5% rate cut in September – rather than the 0.25% currently priced in – went up. Bond markets currently suggest around a third chance of 0.5% next month, but we think it is more of a 50/50.

There are suggestions that this is unnecessary and could either stoke market fears about the economy or increase inflation. We have said all along that the US economy is in a decent position: consumption is solid, while there are no signs of systemic credit stress. Does the world’s largest economy really need sharply lower rates?

“Need” is too strong, but cuts are certainly appropriate. The point is not that the economy is in distress, but that risks have risen markedly. Unemployment has increased slowly but is now at a point where it could quickly spiral if left unchecked and smaller businesses have clearly not been doing well for some time.

Firms have been reluctant to lay off employees – probably because they remember how hard it was to hire post-covid. That could change. Swedish fintech firm Klarna made headlines last week by announcing it would replace workers with AI – which feels like an ominous sign. If that becomes a trend, unemployment could get nasty quick.

In the UK and Europe, growth seems to be a little steadier, possibly because it was not so stellar before. Labour markets are easing at a gentler pace. ECB and Bank of England rate-setters have suggested that rates can come down, but it is not definite. We are pretty sure that rates will be cut again this year and into next, judging by currency strength.

Markets are right to ignore the election

Curiously, markets recently seem completely unmoved by US election drama. Some will tell you that US or global asset values are relatively unaffected by who is in the White House. However this election clearly matters for stocks: Donald Trump and Kamala Harris have vastly different plans for corporate tax, and we have argued that Trump carries a bigger threat to bond markets too.

Markets recognised how impactful the election result could be at the start of July, when the odds of a Trump victory peaked, and investors got excited about tax cuts for small and mid-cap companies. But now, markets are acting as though it makes no difference.

This is because the outcomes are so uncertain and ripe for biased estimation, that it makes sense to treat them as irrelevant – which they clearly are not. The election is on a knife edge in terms of forecasts and betting markets (polls give Harris the lead, but the popular vote doesn’t guarantee the presidency).

The big picture implications of either candidate’s policies are unclear. Trump will cut taxes and boost shortterm US profit growth, at the expense of global trade and possibly long-term fiscal stability. Harris might eat into corporate profit margins but will probably continue the status quo, and might boost long-term growth through government sponsored investment. Markets think neither of these scenarios are ideal, but it is hard to work out which is better.

Markets are also notoriously bad at reacting to elections. They tend to react when big surprises happen, but overestimate both the policy impacts of certain candidates and the economic or financial impacts of those. Election-inspired sell-offs usually make good buying opportunities for that reason – with Trump’s 2016 win being a classic example.

With less than seven weeks to go, commentators have pointed out that a significant proportion of US voters will have probably decided which candidate they want, and news is not likely to change their preference. What matters is whether they actually vote, which we won’t know until the day itself. Given all that, it is reasonable to ignore the US election campaign and wait for bonfire night.

Why investors look so much to the US

We sometimes get asked why we write so much about US stocks and the US economy. We are a UKbased investment manager, with significant investments in UK capital markets – and yet we talk much more about the US S&P 500 than the UK Large-Cap index. This might be a little confusing, and so we feel it is time we briefly explained why the US is so important for global investors – both in terms of economy and its capital markets.

Bigger than ever before

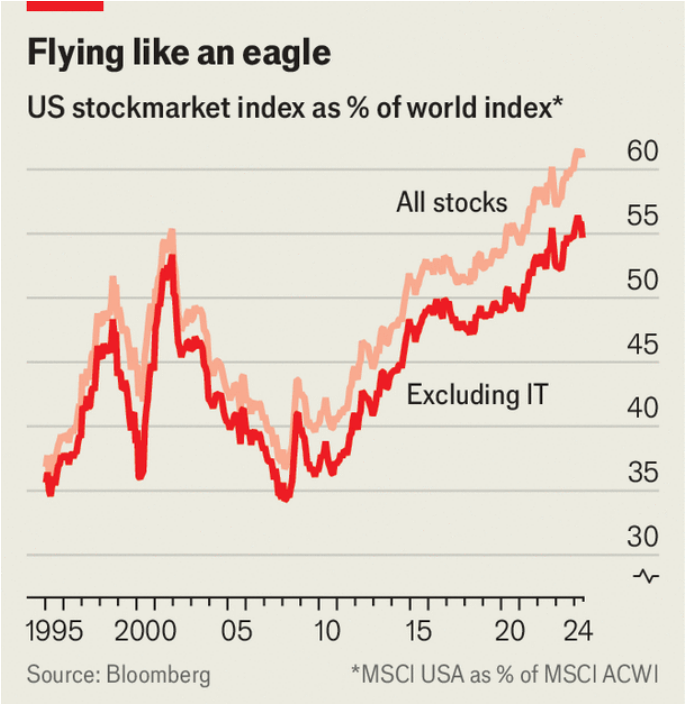

The short answer is that US capital markets are really big. US stocks account for 61% of the entire world’s stock market capitalisation. By contrast, Britain’s stock market makes up just over 3% of the global market. All globally diversified investors will have a significant chunk invested in US markets for that reason. And, even if you avoided American stocks in your portfolio, the interconnectedness of the global financial system means that swings in US assets will have large knock-on effects on most investments – more so than any other region.

That shifts rather than answers the question, however. The US accounts for so much of global assets because global investors are so heavily invested in US assets. But why? It is the world’s largest economy in nominal terms, and so has an outsized effect on global growth. But its share of global GDP is 26% – well below its share of global market cap – and it trades less with the rest of the world than China.

In fact, the US’s share of global GDP has been gradually, albeit unevenly, declining since a post-WWII peak. Its share of the global stock values has fluctuated greatly in that time, but the trend has been up, in reverse of the economy. In the last decade and a half, its economic share has stayed virtually still – while its market cap share has soared. Trying to justify investors’ American focus purely by the size of the US economy does not really work.

The economy matters more to global markets

The US originally gained its economic power because it became established as the world’s premier seller, but it has long since become a net buyer, in terms of exports minus imports. That means, in pure trade terms, money flows out of the US. Another complicating factor is that the US is not even the world’s largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms (China overtook the US in PPP terms nearly a decade ago). That matters in terms of the value of country’s economic activity. In other words, the US economy is pretty expensive.

One of the reason’s it is so expensive, however, is that US economic activity matters more – certainly in market terms – than economic activity from elsewhere. The biggest companies in the world are American, for many reasons. As the dollar is the world’s reserve currency, so much of global trade is priced in dollars, meaning capital naturally flows to the US. This gets called the US’s “exorbitant privilege” in political analysis, and it helps explain why the US can keep consistently running trade and borrowing deficits without the usual penalties.

Current US market dominance is heavily tied to its tech sector. Some have argued that US corporate structures are more suited to technological innovations being quickly monetised and marketed (rather than just discovered, which many countries achieve at least as well). Companies can also quickly scale because there is a fairly homogenous (relative to other large nations or blocs) market of wealthy consumers.

The biggest American companies are global but, strangely enough, tend to derive a disproportionate amount of their revenue from US markets. Amazon, for example, gets more than two thirds of its revenue from the US. What happens in the US is therefore massively important to those companies – and those companies are disproportionately important to the global economy

Can it carry on?

There is a limit to how US-centric global markets can become. At a certain point, investors will realise that other regions are undervalued – particularly if those regions are getting an ever larger share of global GDP, like China or India. But the massive US concentration over the last decade and a half has been prompted by the fact that US tech companies have shown the greatest and most consistent profit growth, and US authorities have left them alone – in contrast to regions like China. If that profit leadership can continue – through AI-innovation, for example – there is no reason why the party should end anytime soon.

That scenario requires a continual capital flow into the US, however. And, as we have argued before, the conditions that underly those flows are being challenged. Donald Trump wants political and economic isolation for the US, for example, while Joe Biden’s administration wants to break up the tech monopolies that pull in so much money from around the world. There may be good reasons for these policies, but they would likely constrain international investors’ American enthusiasm.

There is also the long-term deterioration of US fiscal policy, which we have argued before could be more of a risk to bond markets than investors seem to appreciate. The larger US government debt becomes, the more capital needed to fund it. And, if international capital is not flowing as freely to the US, it will have to come from US domestic savers – which takes money away from stock markets and corporate investment.

In capital market terms, America is as great as it has ever been. That is why we talk so much about it, and that will not change anytime soon. But nothing is forever, and perpetual US dominance is not inevitable.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.