Published

2nd April 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –2nd April 2024

Everyone is an optimist now

For the UK and Europe, last Thursday was the last working day of the first quarter. We will bring you a more detailed round up of asset market performance for March (and the quarter) in the next Cambridge Weekly.

Asset price volatility continues to decrease, much like it has done across the quarter, so we can be reasonably sure that Q1 2024 will have finished strongly for equity markets across the world. Last week had been another reasonable one, with the UK markets playing a bit of catch-up.

The MSCI All Country World Index (one of the most widely used global equity indices) had a small pull back right at the start of the year – somewhat unsurprisingly, given the exceptionally strong Santa Rally into year-end – but that has been the only down week since the end of October. In US dollar price terms, it has since risen almost 25% from that point. Overall, the strong start to 2024 is a pleasant surprise for global investors, considering how well markets performed in the final quarter of 2023. The UK market has been positive as well, but not to the same extent. The UK Large-Cap index is within touching distance of 8,000 points at the time of writing, but our market lacks the same vibrancy as elsewhere.

Flutter Entertainment’s previously announced shift of its primary listing to the US encapsulates the perceptions that our domestic stock market has become a backwater of global markets. We are sad about the perception, but feel this misses the point that the UK remains a very vibrant part of the global capital markets. Our country’s expertise in global investments is immensely strong, and we continue to act as the hub for global capital flows, regardless whether they are transacted through our domestic exchanges, or only advised and arranged here but executed elsewhere.

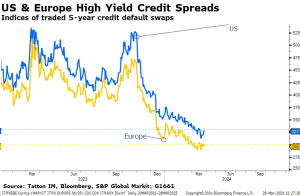

Returning to the market rally, it’s not just equities that have done well. Even though government bond prices have not moved much during this quarter, corporate bonds have done pretty well, meaning a lower cost of finance for companies. Recession fears are fading, so the general environment for borrowers has improved. Credit spreads – the risk premium corporates have to pay above government bonds – have moved from the wide levels seen at the start of November to today’s “normal” levels. The chart below shows how interest costs have come down even for less creditworthy borrowers. The credit spread is shown in “basis points” and one basis point is equivalent to 0.01%.

The five-year government bond yields in the US and in Europe fell sharply from October to the end of 2023, which bought down borrowing costs for all. However, from the start of this year, those five-year government rates have risen a little even though corporate credit spreads have continued to decline. Essentially, this means that many firms’ borrowing costs, on a net basis, have only risen by 0.5-1% since the inflation-induced rise in interest rates started three years ago.

We have mentioned before that we see these moves as signalling a relatively benign equilibrium. Borrowing costs are higher than they have been, but at the same time, growth is stronger than it was pre-pandemic. More importantly, investors and companies increasingly believe that growth will remain reasonably strong. That makes increased borrowing costs affordable for businesses, and arguably justified.

Another market signal of equilibrium is the decline in stock and bond market volatility. Commentators tend to focus on stock market volatility and often use the “VIX” Index. This is a measure of expected volatility of the US S&P 500 over the next 30 days. Through this quarter, expected volatility has declined to levels last seen in the calm times of 2018-2019, although it’s not quite back to the extraordinarily quiescent period in 2017.

Given the strong market performance of this quarter, the next has quite a lot of expected positivity built into it already. Investors are hoping that the world is on a stronger growth path than before the pandemic and there are good reasons to believe that. Consumers have higher savings, relatively less borrowing and employment is plentiful. Companies also have relatively less borrowing, margins have stabilised and profits are growing reasonably well.

The fly in the ointment is that improvements in overall private sector balance sheets have come at the expense of public sector balance sheets. If interest rates are stable, government borrowing will probably not get worse relative to the overall economy, but things are fragile.

Liz Truss, in October 2022, gave us a lesson in how ill-prepared fiscal plans can destabilise government bond markets and create significant pain for many people. Last week, Larry Fink, the CEO of Blackrock Investors, warned that the US might face a similar situation because of its high levels of ongoing borrowing. The Congressional Budgetary Office indicated a similar concern. So, although there is room for expected bond yield volatilities to decline, the upcoming Presidential election could still throw a few bombshells into the market.

Another risk is that the decline in inflation could be challenged. Brent Crude Oil prices have been heading back towards $90 per barrel. This seems to be due to low inventories following the past production cuts, which suggests room for production increases and a stabilisation of the price level. Nevertheless, markets could get spooked.

In the coming weeks, perhaps the biggest focus will be the company Q1 2024 results, to provide evidence for everyone’s extended growth expectations.

Inflation volatility creating inflation?

Central bankers strongly hinted a couple of weeks ago that the inflation beast has been slain. The Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) kept interest rates steady in their most recent meetings, but both effectively confirmed that cuts are coming later this year. The European Central Bank (ECB) was a little more cautious – highlighting sticky services inflation – but weak European business sentiment and a surprise Swiss rate cut suggested that caution might be overdone.

Capital markets need no convincing that the battle is won. Surging prices have come down dramatically over the last year, with the latest CPI (Consumer Price Index) figures showing yearly inflation at little over 2% in the UK and Europe. Sharply higher interest rates, slowing economic activity, and falling global goods and energy prices have had a big impact, but not so big as to threaten mass unemployment. Some commentators call it ‘immaculate disinflation’ – prices coming down without deep recession. Markets have followed the narrative with glee; year-to-date stock returns are strong in the US, Europe and – to a lesser extent – the UK.

Declaration of victory might be a little hasty, however. Key inflationary signals show a downward trend, but the decline is not even. The drop in core service inflation has been much shallower than in goods prices. And, as is well documented, US inflation has proven extremely sticky, falling to 3% last June but not reaching that low since.

Prices in the services sector tend to be stickier than goods, since they are more sensitive to demand and labour market dynamics, and cannot be brought down by cheapening imports. But recent research suggests there could be another reason prices have not budged: inflation volatility. According to a research paper by Evi Pappa of Carlos III University, Madrid, firms are more likely to pass through price rises and less likely to cut prices, not just when inflation is high, but when inflation numbers are rapidly shifting.

Part of this is from the well-known phenomenon that inflation can be self-reinforcing, since higher general price levels can cause firms to charge more – either to maintain profit margins or keep up with wages. That is the dreaded wage-price spiral (or perhaps more accurately, the wage-profit spiral) that central bankers have been scared of for years. But, Pappa’s story adds an underappreciated twist to the tale, that not just price increases but the rate of change can have an impact on price setting behaviour.

This is important because it suggests that inflationary behaviour could still come through even if many inflation indicators are coming down. Intuitively, what drives this behaviour is a sense of price instability. If businesses are uncertain about future input prices – even if prices could go down – it makes sense to keep prices higher, or make yourself resistant to higher prices.

By the same token, consumers will probably be more willing to accept high prices if they have no firm basis of what the price should be. Supermarkets often exploit this phenomenon by advertising apparent discounts, where the non-discounted price is higher than the price before the discount was added. When prices are constantly changing, it becomes very hard to work out what fair value is.

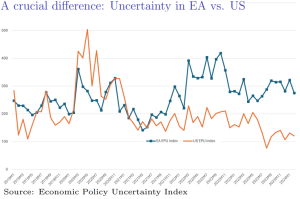

Uncertainty is therefore key. We have been through several years of unprecedented shocks, which led many companies to build up buffers of supply or capital to be less affected by the next one, which increases inflationary pressure. With the world economy currently grappling with climate change, there are reasons to think shocks might become more frequent too. A green energy transition could increase the already considerable oil price volatility, and also push up medium-term costs for companies through carbon taxes or technological shifts. Meanwhile, natural disasters are becoming more frequent, threatening supply chains.

This uncertainty and related price instability is perhaps why central bankers have been reluctant to signal interest rate cuts sooner. Markets were eagerly awaiting looser monetary policy for most of 2023, but were repeatedly disappointed by central bankers’ rejoinder of ‘higher for longer’. Pappa’s research, for example, suggests that rates might need to stay high until inflation is sustainably at or below the 2% target, since it needs to discourage firms from investing in ‘price flexibility’ – i.e. putting extra money aside or buying more stock than needed, for fear of prices rising.

This might also explain why the ECB has been so reluctant to signal rate cuts, despite undeniable signs of falling inflation. Europe has seen more price instability than anywhere else and, with the Ukraine war on its eastern edge, it arguably has more uncertainty to grapple with too.

One problem with this line of thinking, though, is that it focuses almost entirely on the supply-side effects of uncertainty. Just as price instability can make firms more rigid, it can cause consumers to spend less and save more, as they also need to build in buffers. Indeed, we have seen these effects in the UK, Europe, and particularly China, manifested in weak consumer demand numbers.

On this interpretation, the ECB has reason to be more dovish than the Fed – since US consumers have continued burning through excess pandemic savings while others in the developed world have been more risk averse.

It is hard to say which effects might be stronger – the demand, or supply-side uncertainty. The ECB seems to be wary of the supply-side story still, while the Fed remains focused on demand. That makes sense, given how inflation dynamics have already played out on either side of the Atlantic. But it could mean shifting signals from central bankers, if it turns out inflation is not dead yet.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.