Published

29th January 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 29th January 2024

Positive growth sentiment returns

After the bumpy ‘hangover’ start and the volatile two weeks that followed, it looks like investors are finding their feet again, slowly turning January into a far more positive month than many had expected, following the very strong rally into the year-end. As the month draws to a close, financial markets are turning out to be rather quiet, at least in terms of price volatility. Reasonable sums of savings are flowing into financial assets. Companies and governments are able to find willing investors to fund their requests for capital. Therefore, almost entirely across the board, regional equity markets are up another healthy amount. Even China has managed another positive week, with Hong Kong finally bouncing (we look at how sustainable that bounce may be in a separate article). Surplus liquidity searching for attractive returns, is the one market variable that has repeatedly surprised during this highly unusual post-pandemic cycle, and 2024 does not seem to be any different.

As suspected, bond markets are extremely busy this January. They are different to equity markets in that borrowers have to issue new bonds frequently, because older issuance reaches maturity and has to be repaid. We talk about a 10-year bond being ‘long’, but large borrowers end up having to issue new bonds every few months, because of the nature of their rolling book of debt finance.

Because yields rose sharply from the beginning of 2022, many companies across the world delayed refinancing, hoping that yields would surely fall back as the economy contracted, forcing central bank to cut rates. As we know, this did not happen, and so yields have not fallen back to the historic lows we saw in 2021. Nevertheless, with inflation falling, they have declined from the relative highs of 2023. For government borrowers, yields have declined by around 1%, but for riskier corporate borrowers, the turn in sentiment in both markets and economies has resulted in reduced fears of defaults – which has additionally driven down the risk premium (spread), they have to pay above the government. In the US dollar bond market, in September 2018, the US Government was paying 10-year interest of just less than 3%. Now the yield is about 4.1%. A borrower with a credit rating just below investment grade (BB-rated) was paying just over 6% in September 2018, and now will pay interest of around 6.5% according to Bloomberg.

Only 3 months ago, that BB rated borrower was looking at paying over 8%. Perhaps it is no wonder that corporate borrowers are feeling the current yield levels are reasonably attractive enough to replenish their loan capital side.

While we cannot go into the details here, the story is similar in the Eurobond market, which have already seen record issuance for a January. Bloomberg reports that US dollar markets will achieve a similar high point this week.

It is a good sign for markets and economies that more companies are thinking this is a good time to borrow money. This rise in spirits is getting some backing from moves in the commodities markets (which we write about below), and from business sentiment surveys like the ‘flash’ purchasing managers’ index (PMI) surveys from across the world, released last week.

Perhaps sentiment is not racing ahead, but the broad composite measures – which include both manufacturing and service sector companies – are now generally heading above the 50-level which signals the difference between companies thinking they are in growth and decline. Indeed, the US, UK and even China are at or above the 52 level (which aligns with activity at a normal level, and optimum capacity usage).

It is also notable that core Europe is still having a tough time. The composite has edged up from the October low of 46.5, but languishes at 47.9. Services surprised on the downside and fell back rather than rose. Both France and Germany appear to be at the centre of the despondency, while the periphery is feeling better (Greece is doing very well!). There is a positive underlying story in that the manufacturing PMI on its own is rising sharply, in line with other areas, albeit from a lower level. Manufacturing tends to lead services, so we should expect some improvement in the coming months.

As mentioned before, a step-up in Euro-denominated bond issuance could be a positive signal for Europe’s economy, with companies hopefully borrowing to invest and spend. The fall in natural gas and electricity prices has also continued despite the slight rebound in oil prices (the rebound being a probable consequence of the Red Sea problems, and not affecting liquefied natural gas so much).

The European Central Bank (ECB) also did its bit to keep confidence stable with its announcement last week. Nobody expected a rate cut (and none was forthcoming), but ECB President Christine Lagarde said there was “stabilisation” in some wage indicators, and that companies were currently absorbing wage hikes, reducing the risk of second-round effects on prices. She also gave little pushback when asked about a spring, rather than summer, start to cutting rates.

This week is the turn of the US Federal Reserve and then the Bank of England. Again, nobody is expecting rate cuts, it will be all about the comments.

So, markets have returned to that beneficial frame of mind, where optimism is slight and risks have been high, but are falling. That even applies to the dreadful geopolitical situation. Even if it never feels that way when observing geopolitical events and risks, in economic terms the current situation is not getting worse – for example, there has been no notable aftermath from the Taiwan election.

However, the Republican elephant is in the room, and Trump is becoming impossible to ignore. After finishing as the undisputed winner of the primary in New Hampshire (thought to be the one state where he was least likely to win), Donald Trump will probably become the de facto nominee after Super Tuesday of primaries on 5th March. Meanwhile, nobody but Biden is standing in Biden’s way. The 2024 election ends on 5th November, and while a change of candidate would only happen if the chosen nominee could not continue, it is still possible that one or both of the leading candidates could face election-ending legal or health issues. In that case, Convention delegates would be asked to select a ‘unity ticket’.

The geopolitical risks will start to be about whether the next phase of ‘Making America Great Again’ will be at the expense of the rest of the world. Trump has had a habit of making policies on the fly, but seems to have been somewhat more controlled so far. We will write more on some implications over the coming weeks.

Will Xi allow China to profit?

Some relief finally for Chinese traders last week. 2023’s prolonged decline in Chinese stocks had continued through January, turning into a sharp sell-off the previous week. But last week, Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index rose more than 6% during midweek trading, after signs that the Chinese government would step in to stop the rout. Last Tuesday, Premier Li Qiang called for “more forceful and effective measures to stabilise the market and boost confidence”. This lifted Hong Kong-listed equities but left domestic shares only slightly up, with investors aware Beijing’s rhetoric can often be just that. It was followed on Wednesday, though, by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cutting bank reserve requirements, and thereby unleashing a trillion Yuan of lending headroom into the banking system. Both the Hang Seng and the CSI 300 – mainland China’s benchmark stock index – rallied in response.

The PBoC’s cut is significant. Governor Pan Gongsheng promised to lower the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) for commercial banks by 50 basis points (bps), a move that should free up RMB 1 trillion (approximately USD 140 billion) in long-term liquidity. The PBoC will also cut relending and rediscount interest rates by 25bps for small businesses and agriculture. Crucially, Pan also promised policy announcements on improving commercial property loans by the end of the week.

These announcements are big enough on their own, but even more important in context. The PBoC cut RRR twice in 2023, each time by 25bps. Doing so again – and by a bigger margin – shows a commitment to easing policy. And crucially, the announcement came just a day after Premier Li’s speech about state support. This shows Beijing is willing to put its money where its mouth is and – crucially – wants markets to know it.

Investors have doubted this commitment in the past. Policy announcements at the end of 2022 ratcheted up excitement for China’s economy and equity markets, only for a massively underwhelming growth performance to follow. Beijing’s unwillingness – or worse, inability – to pump up the economy was one of the biggest factors behind this. In the end, China was perhaps – as we have commented here before – the biggest market disappointment of 2023.

There have been signs in more recent months that the government will fully step in, but distrust lingers. Recently, the PBoC disappointed markets by keeping its medium-term lending facility rate steady when a cut was expected. Prolonged economic weakness and recent deflation set the scene for a supportive rate cut, but officials continued their reluctance to ease credit conditions.

That reluctance is a longstanding policy. For years, Beijing has sought to deleverage China’s economy after the old debt-fuelled growth model threatened to destabilise its financial system. This led to a myriad of hits to consumer and business sentiment over the years – exacerbated by years of on-off lockdowns – including the ongoing property malaise. The Communist Party does not want to expand a credit bubble it has tried so hard to deflate, but this increasingly looks like the only option.

However, overall appetite for credit – both from households and private businesses – is extremely low. Informal peer-to-peer lending, which used to be one of the major forms of lending in China, has dramatically shrunk. This is partly due to the crackdown on shadow banking, but also due to the private sector simply not having the capital to do so. This has led to a classic credit crunch: since most people are reluctant to borrow, the only ones that borrow are those in distress. Hence, commercial interest rates are high because lenders are exposed to significant credit risk – despite overall credit demand being low.

Easing credit conditions would help, but authorities are still holding back. The PBoC, for example, seems intent on using RRR cuts and other liquidity injections to rescue the economy, but not benchmark interest rates. When you factor in recent deflation, that amounts to an increase in real (inflation-adjusted) rates, despite a sluggish economy which demands the opposite.

A commitment to supporting credit markets is needed. The PBoC’s words and actions are certainly a step in the right direction and, coming so soon after Premier Li’s speech, will certainly soothe some investor concerns. But to be truly effective, Beijing will need to convince both borrowers and lenders that lending is worth it – i.e., improve general sentiment. With the economy sputtering, that will be a difficult task.

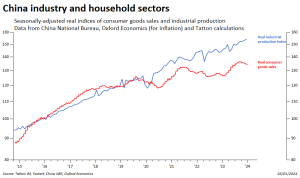

The official data still say Chinese growth is around 5%, but even if those figures are true in aggregate (and there are many reasons to be sceptical), they clearly do not reflect the realities facing most businesses and households. Confidence that things will improve is sorely lacking, which has led to savings being underutilised and hence a shortfall in demand. The chart below illustrates this, as it shows that despite the government’s declared goal of making the economy more centred on domestic consumer demand, the opposite trend has occurred over the past five years. While industrial production has continued on its previous growth trajectory, private demand growth has tailed off. This has effectively helped the rest of the world in its fight against inflation through lower goods prices, as Chinese producers have tried to reduce their inventories, but the Chinese economy has certainly done the opposite to the intended rebalancing towards domestic demand.

Beijing is clearly trying to reverse this trend and improve economic confidence. As well as lending, it announced last week a plan to directly support the stock market through share buybacks of large state- owned enterprises. Policymakers want to mobilise RMB 2 trillion (USD 280 billion) held in offshore accounts by its national champions, a move which has helped stabilise markets.

Ultimately, though, attempts to support short-term confidence in the economy or financial system do not address a core reason for why businesses and investors lack confidence to begin with. During the crackdowns of the last few years, there has been a growing sense that President Xi Jinping is against not just excesses, but private sector profit altogether. He has made it clear that private power cannot be allowed to rival the state (as in the case of Alibaba founder Jack Ma), but this seems to have filtered through to profit-making in general.

People are willing to take advantage of the short-term market opportunities the Party hands out, but to truly invest in long-term private sector growth, they need to know they will be allowed to profit without negative comeback. This needs consistent messaging, ideally from Xi himself. Without that, the decline will be hard to stop.

Commodities and growth

Commodity prices are resolutely stable. Since the start of January, the Dow Jones Commodity Index has been virtually flat, increasing by just 0.15% year-to-date. That is either a good or bad sign, depending on how you look at it. Commodities fuel the global economy – sometimes literally – and are therefore a sign of global growth. Considering the intentional slowdown in global growth we have seen recently, with mild recessions in some major economies, a stable if unspectacular patch should be welcomed. On the other hand, this stability comes after a protracted downturn for the commodity sector. Dow Jones commodities have lost nearly 9% on a one-year basis at the time of writing. Staying on the level is less impressive if the level is already low.

Of course, much of that downturn is about oil, which went through a mini boom and bust cycle in the second half of 2023. Supply side contraction – a coordinated effort from OPEC+ – pushed crude prices up significantly into September, but the rally completely unwound thanks to weak global demand. In a sense, oil’s recent ups and downs show why it is no longer a great indicator of general economic conditions: prices rose because the cartel made them, but these acted as a tax on consumers and non-energy companies that were already facing tough conditions.

Metals, in particular industrial metals, are arguably a better signal. The S&P Industrial Metal index has been flat for some time, currently at the same level it was in May last year, and with only a narrow trading range since then. As the chart below shows, metals became detached from energy prices last year, and that detachment is still going.

Again, stable metals prices are encouraging, all things considered. Global manufacturing has been struggling for a long time, and the latest purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) business sentiment gauge show this is still the case. While there has been improvement across the board, manufacturing PMIs still point toward contraction in the UK and Eurozone. The only exception is the US, where the manufacturing PMI unexpectedly jumped to 50.3 in January (a reading above 50 suggests expansion). US resilience and outperformance is nothing new, though, and is offset by weakness elsewhere – particularly the disappointing China.

There has been a gentle slide for metals through January. While this is a little concerning, it is probably more about the strength of the US dollar – which commodity indices are priced in – than underlying economic weakness. Indeed, metals rose slightly through the autumn and into the end of the year, as markets began to get excited about the prospects for global growth. With central banks expected to cut interest rates this year – and a new growth cycle sure to follow – we would expect a pick-up in futures pricing for metals, in line with a recovery in manufacturing.

The problem for metals is that they cannot sustainably rise on hope alone. Like all commodities, metals futures are subject to short-term speculation, but are ultimately physical materials that need to be financed, stored, transported and used. The cost of storage has risen dramatically in recent years, thanks to the massive step-up in developed market interest rates, which led to a big increase in the cost of the tied-up capital. That means inventories are generally lower, which means prices are much more sensitive to final demand. As such, we are unlikely to see a sustained pick-up in metals prices until growth and demand actually come through.

That could take a while, but there are encouraging signs. The Chinese economy is one of the biggest drivers of commodities pricing, and it has been struggling for a long time. That resulted in a Chinese stock market sell-off earlier this month, as outlined in the previous article. Interestingly, though, pessimism about China is not reflected in prices for key indicators like iron ore. The two used to rise and fall together, but weakness in the former is no longer damaging the latter. State support is a key factor. The Chinese government promising to pump money into its ailing economy is having an impact on factories – the latter now not as afflicted by the same deflationary pressures as others.

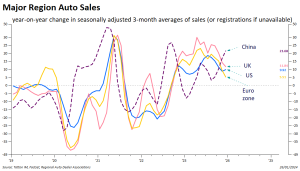

One of the more encouraging signs is that car sales are clearly picking up, as the chart below shows. This is crucial, since China is by far the world’s largest market for cars, and vehicle sales are often seen as a proxy for consumer confidence. Demand is picking up, though we need to keep an eye on how this trend fares through the new year break in February.

Despite that pick up, palladium – used in catalytic converters and hence an indicator of car manufacturing (of conventional cars) – is extremely weak. The Palladium Futures index has lost 11.7% in January alone and 43.3% over the last year. There is still a big supply overhang in the Chinese market, thanks in large part to the overproduction of newer electric vehicles at a time when the economy and consumer confidence was weakening. For all the positive demand signs, inventories still need to be worked through.

That could happen quickly, though. Copper prices are a good example. Having endured some recent weakness, copper looks set to turn around as demand improves and a series of supply-side crunches bite – compounded by producers running down their stocks. A similar dynamic could happen for metals broadly: the global economy picks up just as inventories become depleted, giving producers a great deal of pricing power. For the global economy more generally, that brings its own inflation complications. Ultimately, though, if and when metals do rise it will be a positive sign.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.