Published

28th May 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –28th May 2024

Nvidia versus the Fed

Following the strong upwards surge in stocks and bonds at the beginning of May, capital markets have recently moderated and were mostly flat, to slightly down, overall last week. Britons were preoccupied with Rishi Sunak’s surprise election call – polling now less than six weeks away – but capital markets clearly had bigger things to worry about. Stellar results from AI tech giant Nvidia excited, but minutes from May’s meeting of the US Federal Reserve, dampened investor sentiment in equal measure. It was the US economy’s back-and-forth narrative in a nutshell: healthy growth and profits, but stock market valuation held in check by the resulting headwinds from higher interest rates for longer.

No election nerves

First, matters closer to home. It was not just global stocks that shrugged off the election announcement; the UK Large-Cap index barely reacted either. UK equities were virtually flat last Wednesday, but fell into the week’s end, following the negative lead of the US markets. For the globally focused multinationals that make up our main index, Fed policy is seen as more important than domestic politics.

Markets’ nonchalance towards British politics also reflects the view that no major economic or financial changes are expected. With the Labour party’s commanding lead in the polls, betting markets have it as a near-certainty that 14 years of Conservative-led rule will end. But Keir Starmer has committed his party to tight spending rules, so the economic effects – at least in the medium-term – are likely to be marginal.

That is not to say there will not be any. If Labour manages to live up to its housebuilding pledges, it should provide a moderate growth boost – though it will not reverse the effects of years of undersupply. In the long-term, taxes will probably be higher than they would have been under continued Conservative rule, but public investment will likely be higher too. Like the last Labour government, Starmer’s party is focused on ‘crowding in’ private investment for infrastructure.

Closer ties with the EU would go a long way to repairing the adverse growth effects of Brexit, which is widely quoted to have cost the UK economy 5% relative to comparable G7 economies, but Starmer has already ruled out rejoining the single market or its customs union. Without vociferous Brexiteer backbenchers, a Labour government might at least have more conciliatory relations with our largest trading partners – so small trade improvements are possible. Perhaps this is why sterling strengthened against the euro following Sunak’s announcement.

In any case, the Bank of England’s timeline for rate cuts will be much more important for short and mediumterm prospects. This will be unaffected by the election, and looking at forward rate expectations, as implied by the bond markets, August remains the most likely date for a first cut. Recently weak consumer data should solidify the Bank of England’s decision.

Nvidia ‘fights’ the Fed – and loses

As mentioned, US events last week were much more important for markets’ overall mood. Nvidia’s incredible earnings growth for the first quarter showed that the AI boom still has plenty of way to go. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang beamed that generative AI is the “next industrial revolution”. With year-on-year revenues up 262% and profits six-fold (!), the chipmaker is clearly positioned as its baron. The meteoric rise of Nvidia’s market cap – which we discuss in separate article – continues.

In the early part of last week, the discussion was about the chipmaker’s outsized influence on US and even global equity market sentiment. Last Thursday showed the limits of that influence, however. Minutes from the Fed’s meeting earlier this month were released, and the tone of discussion was notably more hawkish than markets had been expecting. Despite Nvidia stock jumping 9.3% on the day – and adding an incredible $218 billion to its market cap in the process – the wider S&P fell 0.74%.

The nerviest part for investors was reported talk of whether another rate rise might be needed. While the Fed’s timeline for rate cuts has been consistently pushed back this year, investors have not dared whisper the word hike. Implied rate expectations shifted and shorter-term bond yields (in particular the 2-year yield) picked up, making equities less attractive.

Checks and balances

To be clear, no one thinks a rate hike is the Fed’s likely next move. “Various participants mentioned a willingness to tighten policy further should risks to inflation materialise in a way that such an action became appropriate,” according to the minutes from the May 1 st meeting, but there is little sign that chairman Powell agreed with those sentiments. The minutes are backwards looking too. Inflation data since then has been more comforting, with a CPI report from mid-month suggesting that the 2% inflation target is on track – albeit a slow, bumpy track.

Really, it should be no surprise that some policymakers feel tighter policy might be needed if inflation stays elevated or moves higher. The US economy has comprehensively proved doubters wrong over the last couple of years, with both resilient growth and consumer sentiment. We have known for a while that inflation pressures are the natural consequence of that strength. The Fed wants to support growth, not choke it off with punishingly high rates. But, many signs suggest that the economy does not need this support and can handle high rates just fine.

The growth-inflation dynamic is currently acting like a system of checks and balances on capital markets. Investors naturally get excited about strong business sentiment and profits, but these come with inflation pressures and ‘higher for longer’ interest rates. As happened last week, the Fed does not actually have to do anything to keep markets from overreaching; the push and pull of growth and inflation expectations does it for them. Decent stock returns, underpinned by earnings growth, are likely in this environment – but melt ups are not. To us, that seems like a reasonable trade-off for long-term investors.

AI trade broadening?

Capital markets held their breath for ‘Nvidia day’ last week. Such is the excitement around the Artificial Intelligence (AI) investment craze – and the high-tech microchip producer’s dominance within the space – that Nvidia’s quarterly earnings results were anticipated as one of the week’s biggest events, on par with the Federal Reserve’s meeting minutes published on the same day.

The leading AI chipmaker did not disappoint. Compared to a year ago, Nvidia’s revenues soared 262% in the first quarter of 2024, smashing through already elevated expectations. The company’s stock price was lifted by the stellar results, but they were not the only ones: In anticipation of Nvidia’s results, US stocks more broadly rallied. Bloomberg’s John Authers argued last Wednesday that the strength of Nvidia’s results would determine which way equities will trade in general. He was proven wrong in the end, but the very fact people expect Nvidia to drive the market speaks volumes.

Since the release of ChatGPT kicked off an investment frenzy for all things AI, Nvidia has been the undisputed winner. It is now the world’s third largest company by market cap, with a staggering valuation of $2.5 trillion. If you bought and held Nvidia last June when it first broke the $1tn barrier – and hence was already extremely highly valued – you would have doubled your money in less than nine months.

This incredible action has many investors worried that AI stocks in general, and Nvidia specifically, might be overvalued. 2023 was a landmark year for the chipmaker, with demand massively bolstered from the growing sector of Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. These profits, and the potential for Nvidia to dominate a potentially huge LLM market, propelled Nvidia’s stock, but its profits for last year were still lower than Home Depot, and only slightly above Russia’s sanction-hit Sberbank.

As we have argued before when discussing the AI stock market frenzy, a few things are crucial to bear in mind. First, stocks can be overvalued even if they have a lot of underlying potential, and, for new technologies, this potential and the timing of it becoming commercial reality can often be poorly understood or mispriced. The internet is probably the most transformative technology since the discovery of nuclear fusion, but the dotcom bubble still blew up tiny companies to entirely unreasonable proportions. Investors not only misjudged how long it would take for the internet of things to become reality, but also took a somewhat scattergun approach, not being able to foresee which proposition would succeed or fail.

Second, overvalued does not necessarily mean a bubble. Nvidia’s future earnings potential is undeniable, and LLMs are already driving efficiency gains across the world. Even if investors are more excited about these stocks than calm analysis of future earnings prospects would recommend (and that is a big if), that does not mean AI is a bubble waiting to burst. Stock market bubbles are usually characterised by exuberance, or money flowing into poorly understood avenues on the basis of buzzwords alone. These conditions usually require capital being readily available – since people cannot throw money around if they do not have any – but current financial conditions are more prohibitive.

It seems unlikely that markets are exuberant at the moment. AI stocks have become very highly valued, but this is also tied up with the high valuations attached to US technology stocks (most of the popular AI-related investment plays are in the US) and, considering the economic impacts that LLMs and generative AI could have, these valuations are arguably justified. Nvidia’s first quarter earnings were 600% higher than a year before. Such growth may feel unjustified, given the still only limited impact AI has had on businesses’ productivity, however, its potential may well be just as outsized as that of the internet 25 years ago. A Goldman Sachs report from last year claimed that generative AI could boost labour productivity enough to increase annual global GDP by 7% over a 10-year period.

The same report argued that 300 million workers worldwide could lose their jobs to automation. If that were true, it would certainly mean economic disruption and political pushback in the short-term, even if it meant productivity gains down the line. Considering the lofty predictions being made of AI’s impact, investor reactions look fairly tame by comparison. For example, investors had a mixed reaction to the IPO of chip designer Arm last autumn. This shows they are paying attention to the ways in which AI-related companies can actually turn a future profit, rather than just chasing innovation on the basis of buzzwords. Investors are not in droves resorting to the ‘scatter gun’ approach that failed so many with the 2000s Dot Com craze.

This considered approach contrasts with the more sensationalist trends we saw during the pandemic, when rates were lower and retail investors had more money to speculate with. Recently, the AI investment theme has broadened in terms of the stocks favoured – with investors now looking for second-round beneficiaries, like the providers of materials or energy needed for large data centres.

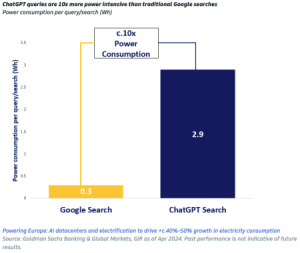

In terms of broader economic changes, the new computing technologies may cause elsewhere, it is sometimes underappreciated how energy-intensive generative AI is. As the chart above shows, the power needed for a ChatGPT search is several times that needed for a standard Google search. Researchers at Goldman Sachs estimate that power demand from data centres will more than double by 2030, which will significantly boost aggregate electricity demand and likely require significant investment in utilities infrastructure.

Energy providers, as well as key industrial metals like copper, will be big beneficiaries of these shifts. Goldmans think that utilities capex and those providing financing for power purchase agreements could therefore also benefit from AI growth. These areas are seeing a pickup in investment. This is a sign that markets recognise the need to generate long-term profits and not just buzzwords. As Nvidia day shows, AI brings plenty of profit opportunity for investors. Investigating what those are – particularly with tech valuations so high – is crucial.

US election: it’s politics, stupid

President Biden’s State of the Union Address in March was full of praise for the US economy and his role in supporting it. He has a point: US growth has stayed remarkably strong over the last few years, despite decades-high inflation and the sharpest interest rate squeeze in a generation. For capital markets, the key debate is whether growth is too strong, or employment too high, to warrant rate cuts from the US central bank, the Federal Reserve Fed). That debate creates its own issues for Americans – particularly those having to reservice outstanding debts at higher prices – but the consensus is that, on aggregate, businesses and households are in a strong enough position to handle it.

And yet, recent poll findings show that voters are unhappy with Biden’s handling of the economy. The Financial Times reported a couple of weeks ago that 58% of Americans disapprove of Biden’s economic policies, versus 40% that approve. Disapproval has grown since April, and nearly half of respondents said that Biden had hurt rather than helped the economy, with only 28% (down from April’s 32%) thinking he had been a benefit.

This is bad news for the President as we head towards the November rematch with Donald Trump. Biden needs to not only improve economic conditions but convince people that those improvements are happening. The biggest concern, perhaps unsurprisingly, is inflation, given its impact is experienced by everyone. Apart from last month’s figure, consumer price rises were above economists’ expectations every month this year. The Financial Times also argued last week that disappointment with Biden’s economic policy is in large part down to US inequality: less well-off Americans have struggled more with inflation and interest rate hikes than those with savings, meaning the effect on how consumers feel might be negative even if national economic data suggests strength.

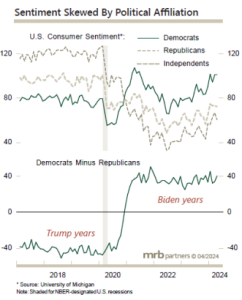

Biden should certainly keep that divide in mind, but even so it will probably be very difficult to convince voters that the economy is doing well. This is because people’s perceptions of how the President is handling the economy might be more dictated by political allegiance than real economic performance. As the chart below shows, US consumer sentiment (i.e. whether people feel optimistic or pessimistic about their personal economic outlook) varies dramatically by party political allegiance.

Economic sentiment has always diverged by political opinion, so in a sense this is not surprising. If you are confident in how the economy is going under a particular president, you are more likely to vote for that president than if you think the economy is going poorly. This is just a restatement of the classic political mantra “it’s the economy, stupid”, and Democrats and Republicans have always disagreed about how things are going.

There is a case to be made that the causation goes the other way around, however. Votes can be fleeting and liable to switch depending on sentiment, but there is a clear difference in consumer sentiment by party affiliation. In the polarised US political landscape, this affiliation does not change too much. Moreover, the divide between Democrats’ and Republicans’ economic outlooks more than doubled between the Obama and Trump presidencies. The gap has actually shrunk somewhat under Biden, but it remains significantly larger than the decades before.

Near-term inflation is one of the key parameters Democrats and Republicans disagree on. Expectations about long-term inflation are actually pretty similar regardless of who is in the White House, but the political difference in inflation expectations for the year ahead are remarkable. Democrats were scared about inflation under Trump but now seem sanguine, while Republicans were completely relaxed until Biden came in and are now very worried about inflation.

This flips the old political wisdom on its head. Rather than votes being decided by how people feel about the economy, Americans’ views on the economy seem to be largely down to whether their preferred candidate is in office. This also fits with the general separation between economic and political sentiment in the US: American politics has become so bitterly divided in recent decades that, according to widespread media reports, a good chunk of the public actually expect a civil war in the near future, but those fears have apparently done nothing to deter growth. Maybe the more accurate slogan is “it’s politics, stupid”.

This makes it very difficult to predict how economic factors will impact November’s election. Inflation and higher interest rates are likely to be a big topic – with anxiety about rates growing for businesses and households – but how much of this gets through to voters is another matter.

To make things even more complicated, the US economy itself is hard to interpret at the moment. Growth is clearly strong, and inflation is proving more sticky than elsewhere, with inflation only very slowly converging to the Fed’s 2% target, but the central bank still seems eager to push ahead with rate cuts. Even if it does not, the general expectation displayed by equity valuations is that profit growth should be enough to sustain healthy markets. This is of course linked to the aforementioned point: for as long as sticky inflation is an expression of growth, profit growth is expected to hold up. There are signs of strength and occasional signs of weakness, but the macroeconomic backdrop means these are hard to put into a consistent narrative.

The political divide in economic sentiment is yet another complicating factor. Republicans are likely to see good news as bad news – in the sense of fearing growth is inflationary – as we head into November, while Democrats will likely see good news as good news.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.