Published

27th August 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

Late Summer heatwave

Global stocks continued their climb higher until the latter part of last week. The rise up until last Wednesday had shown remarkably steady gains in daily terms. When you put that together with gains over the last few weeks, equity returns have been very impressive. From Monday 5 August – the start of that day marked the nadir of the summer sell-off – the MSCI World Index gained more than 8% in US Dollar terms to last Wednesday 21 August. That is quite the turnaround from the panic that came before. Implied volatility has fallen sharply after the early August spike, and investors seem to have chased their fears away.

Last week’s main political event was the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Despite the clear feel good factor for the Democrats, it hasn’t made much impact on the way the markets see the likely outcome. The political betting market has both candidates absolutely neck-and-neck.

The main financial event took place on Friday, with Jerome Powell speaking at the Jackson Hole conference in Wyoming. He confirmed that his focus, and the focus of the Federal Open Market Committee, is now on employment. He described the labour market as being less tight than in the months leading up to the Pandemic. A rate cut in September of at least 0.25% is already fully discounted by the market, and his comments are leading many to expect 0.5%. Stock markets are seeing it as good news and the S&P 500 US Equity Index ended the week strongly.

As we wrote the previous week, though, this market optimism is a little unnerving. Background economic conditions are perceived to be better than feared at the start of the month, but may not have improved to the level that the rally would suggest. The medium-term outlook is solid, but markets have arguably been running a little hot again.

Meanwhile, US stock index returns are flattered because they’re quoted in US dollars. So far this month, the dollar has been slipping against major currencies, and Jerome Powell’s comments have dented the US dollar again.

An unusually good fortnight

The market recovery from early August has been remarkable. US stocks in the S&P 500 are up around 8% over the last two weeks, putting this period in the top percentile of two-week periods in the past 50 years. Even Japan’s stock market – which suffered the worst sell-off of any major region at the start of this month – is nearly back to its end of July level in local currency terms. It has recovered fully in sterling terms, thanks to the strength of the yen.

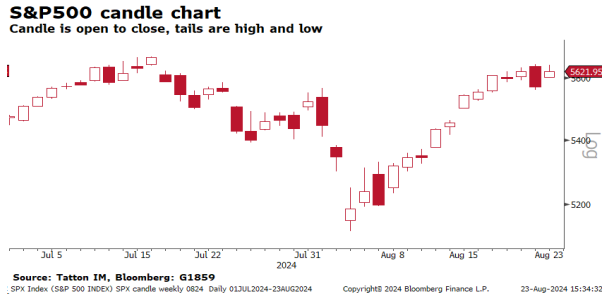

The path up has been smooth, too. The chart shows the S&P’s daily performances since the start of July – with white bars representing up days and red bars down days. Last Thursday was the first daily loss of any note since 8 August, whereas the period before was marked by a series of losses and gains. This trading pattern does not happen very much after a sell-off, as we have noted. Volatility usually acts like a pendulum swinging to a gradual stop. This time, it stopped dead almost immediately

Markets seem optimistic, but it would be wrong to think that everything is okay. Softening growth and inflation implies somewhat less positive company earnings. Meanwhile, equity valuations – most notably in the US – are still pretty high. These are not barriers to medium-term returns, but it is strange that investor worries have quickly dissipated; bears are few and far between. As we know from last week’s weather, at this time of year, two weeks of heat are often followed by another squall.

Does dollar weakness mean US weakness?

The rally has gone hand in hand with a weakening of the dollar over the past month against a range of other currencies. Investors tend to associate periods of dollar weakness with strengthening global growth (and so it can be a broad “risk-on” signal), since US demand creates stronger trade flows, benefitting the global economy. But, in this case, dollar weakness may be more a function of the slowing US growth narrative, with impaired trade flows still affecting the rest of the world.

Over the summer, there have been several signs that US growth outperformance was waning – most notably in the increase in unemployment. This is a key reason why markets are expecting sharper rate cuts from the Federal Reserve.

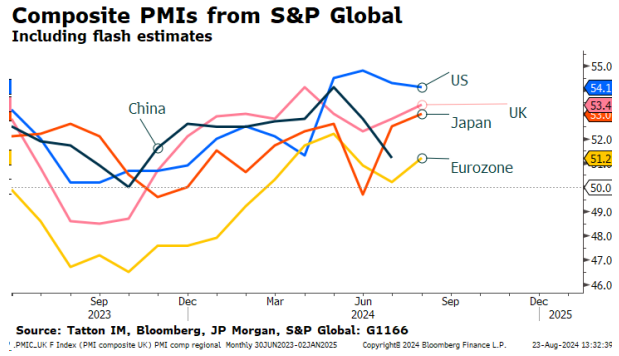

The “flash” purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs), based on a subset of survey responses, give a useful global comparison. According to these, global growth is likely to improve. All areas are above the neutral 50 level and all (except the US) strengthened from July.

The US PMIs have been much more positive than the downbeat ISM reports on business sentiment (which are similar in approach and have a longer history, but have fewer responders). Despite disappointment in manufacturing, the composite US PMI for August was above economists’ expectations. It fell slightly but the level remains buoyant. The only negative signal came from the employment indicator, which showed a weakening in services for the first time in three months.

Company earnings forecasts continue to go up too, which we would not be seeing if growth was about to turn negative. There was some suggestion last week that investors are a little nervous about Vice President Kamala Harris’ economic proposals, which include some price controls. Market intervention policies from US presidents are historically unusual, but her announcement could be a sign of how much US political debate has changed in a post-Trump world. In any case, though, US corporate earnings still look strong and are unlikely to be hurt too much be either candidate winning.

Goldilocks doesn’t mean strong growth.

The recovery over the last few weeks suggests a ‘goldilocks’ mentality in markets. Investors are happy with slightly slower growth if it means rates can be cut – but that also means slowing earnings growth. Stocks did well in that environment in the 2010s, but we need to be aware that it comes with fairly lethargic growth. That challenges the recent positivity around small and mid-cap stocks, for example.

There is also a possibility that the goldilocks narrative could become self-defeating. Markets do not mind slower growth because there are assuming a sharp rate cut path, so valuations are supported. But those expectations are themselves supporting corporates through lower borrowing rates. With that dynamic in mind – and growth still holding up okay – the debate now is whether the economy really needs drastically lower rates.

Last weekend’s Jackson Hole conference had the main speeches but much of the interesting stuff was in the detailed papers. Still, the headlines will revolve around the main messages: Powell is adding to the recent dovish messaging, arguing that recent employment trends are definitely soft and should not be allowed to worsen. Inflation is declining and is not threatened by tight labour markets, which allows short-term rates to fall, which in turn should ensure that growth remains at a comfortable level. Do not expect any talk about politics or any of the policies proposed by the US Presidential candidates

Still, given everything we argued above, last weekend could of been a potential banana skin for markets. The Fed’s messaging is increasingly about the economic downside, which might raise fears in a sensitized market. Another bout of short-term volatility is not a problem for long-term investors, but we should not be lulled into a false sense of security.

Who’s afraid of UK wage rises?

At the start of August, the Bank of England (BoE) cut interest rates for the first time in more than four years. The decision looks fairly straightforward on the face of it: CPI inflation was bang on the bank’s 2% target in May and June (though slightly above at 2.2% in July), and rates are economically restrictive. But Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members only approved the cut by the narrowest of margins (five votes to four) and governor Andrew Bailey warned that further rate cuts were not a given.

A few interesting things have happened since then. Some of the MPC’s more hawkish members have reiterated that inflation pressures still need to be dampened – wages in particular. And in the last couple of weeks, the government has offered pay rises to public service workers. Railway workers have been offered a backdated increase and union bosses have recommended members accept, while Chancellor Rachel Reeves has offered junior doctors a raise worth 22% over two years. This has sparked accusations from opposition politicians and disapproving media publications that the government could stoke further wage inflation.

Despite these concerns, bond markets’ implied expectations for UK rates over the next few years are significantly lower now than a month ago. This is part of a general move down in rate expectations across developed markets – a reaction to lower global growth forecasts and nervy capital markets. But bond traders would not bet on a steeper path of rate cuts if they thought that UK inflation was about to bounce back hard.

Put simply, we do not think that recent pay rises, or any that are likely to follow, will increase downstream inflation. They are unlikely to influence the MPC’s rate decisions too much either. In fact, we think the BoE probably has more room to cut than it will allow (or perhaps be allowed to). Governor Bailey made similar comments on wage inflation after the BoE’s cut. When the suggestion that public sector pay deals could reignite inflation was put to him, he replied that the “back of the envelope” calculation suggested a “very small” inflation increase.

The MPC’s biggest concern in recent years has been a ‘wage-price spiral’, in which higher wage demands lead to businesses putting up prices, creating higher wage demands and so on. Spiral fears have dissipated in recent months, though, as it has become clear that wage pressures have fallen. Year-on-year core inflation – excluding volatile elements like food or energy – has been consistently falling since May 2023, dropping to 3.3% last month.

Services inflation, which is much more sensitive to wages than goods prices, fell to 5.2% in July, below economist expectations and the lowest rate in over two years. This is still high in historical terms, but we have every reason to expect the normalisation of service prices to continue. The slide in energy prices is offsetting wage pressures for many firms, leaving their profit margins intact. Even if energy prices go up from here, wage demands will likely slow due to the consistent drop in headline inflation. Many pay packets (like some in public sector jobs) are linked to CPI, either contractually or simply because of what workers ask for.

There are, of course, still policymakers nervous about wage inflation. Catherine Mann – one of the MPC’s most hawkish members who voted to keep rates high – emphasised the wage-price spiral again the previous week, warning that wage inflation dynamics “will take a very long time to erode away.” Her argument is that the recent price spike has changed the labour market’s structure, and that labour has gained more pricing power.

These claims are hard to evaluate so soon after the fact, however, as cyclical effects are still present. If history is anything to go by, there seems to be a natural limit on how long prices can spiral. There is a strong argument to be made that we hit that limit a while ago, and price pressures have been cooling since.

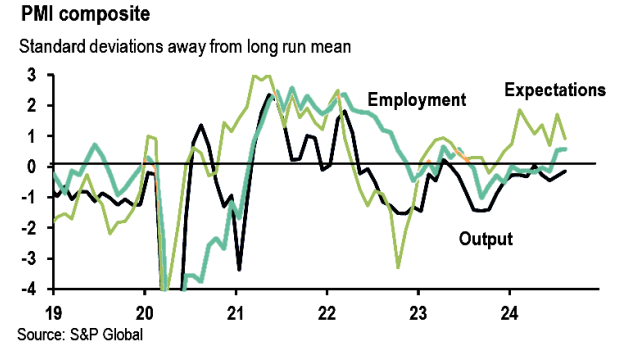

Last week’s initial (“flash”) PMI data showed the input price component of the services PMI – which we can treat as a proxy for wage pressures – took a large step down from 60.4 to 58.7 and is now close to its long run average. The August output price PMI was at 55.0, down 0.3 from July’s level but less of a fall than the input price PMI. Perhaps this is indicating that businesses are experiencing growth and have pricing power.

Allan Monks of JP Morgan points out that, although the recent upswing in growth may be pulling in more labour and resources, but it is also being met by stronger productivity gains.

The employment reading from the PMI was mildly firm and stable at 52.5 in August, with a small gain from July, after last month’s shift higher. Monks equates this with job growth or around 1%. Still, the employment PMI is not as strong as the output price PMI. There has been a recent small rise in high frequency vacancy data from Adzuna, perhaps signalling an end to the loosening trend, which had been evident in declining ONS vacancy data. Still, these signs of a firming in labour demand are tentative.

If wages were about to spiral again, we likely see wage-sensitive price levels coming in above expectations – but we saw the opposite last month. Certain public sector workers are getting larger pay rises than we have seen for a while, but these are mostly in areas where real (inflation-adjusted) pay has been consistently falling for years. These ‘catch up’ pay rises tend to be less directly inflationary, particularly in public services, where end prices are influenced by government policy.

Bond markets seem to agree with this benign outlook for inflation, predicting another BoE cut in the Autumn – perhaps as early as September. The UK’s expected path for rate cuts is not as steep as the US or EU, partly because Britain’s growth prospects have held up okay. But as we have argued before, the BoE is also structurally more hawkish than its peers in terms of legal framework (its 2% inflation target is set externally by the government, while other central banks have discretion over targets).

Hawkish MPC members like Mann will therefore push for keeping rates high. Economic data will influence the majority opinion, though, and that points to a steady decline in rates. Nothing in the recent wage data suggests otherwise.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.