Published

26th February 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 26th February 2024

M&A activity sets growth against value

Equities have moved higher again this past week, with gains made across global markets. Even China put in another week of positive returns, following the largest ever cut to the five-year housing loan prime rate (admittedly only 0.25%). Government bonds have not done so well, with yields rising slightly after a small rebound in general economic growth optimism. Corporate bonds fared better as yields remained broadly unchanged, on the back of that optimism leading investors to judge that credit risks are likely to recede even further.

Last week, we gave a fairly downbeat update about the potential for near-term UK economic growth after the release of the gross domestic product (GDP) data for 2023. During the past week, some economic data reinforced the story that the UK remains in the doldrums. GfK released its consumer confidence survey results for February, showing that the long-running Consumer Confidence Index fell from -19 to -26, while all measures were down in comparison to January.

Joe Staton, GfK’s Client Strategy Director, said, “This is the lowest headline score since January 2021, one of the worst points in the Covid crisis. While all measures have fallen this month, the two forward-looking indicators tapping sentiment over the next 12 months on personal finances and the wider economic situation are showing the biggest falls – these are down 12 points and 11 points, respectively. There’s clear anxiety in these findings as many consumers worry about balancing the household books at the end of the month without going further into debt”.

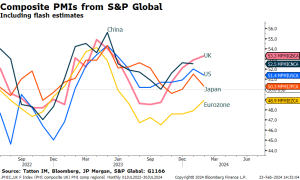

And yet… UK business confidence is picking up! Many investors, including ourselves, put a lot of store in the Purchasing Manager Survey Indices (PMIs) and the February interim ‘flash’ PMI estimates showed services doing particularly well, with manufacturing less well, but still better than January. The overall composite had a welcome rise, better than the US and the Eurozone:

So, should we be downbeat after all? The PMI data is definitely good, with companies getting more positive on their outlooks and therefore on their hiring and business investment intentions. Europe, especially France, has also improved. although things are still only getting to be flat. With interest rates still high relative to activity, it’s not so likely that there will be a drawdown of domestic savings and increased consumer demand. The best hope for both the UK and Europe is the resurgence of China. The US has been strong, but not much external demand is emanating from there. Overall, for the rise in optimism to be maintained, we think rate cuts in relatively short order are still needed on this side of the Atlantic. The good news is that China may well be starting to show more optimism as well. We will get its PMI data at the start of March.

Given how much the productivity improvement hopes around artificial intelligence (AI) have elevated investor sentiment, Nvidia’s Q4 2023 results announcement and guidance for Q1 2024 last week was as much talked about as a market driver as we usually only experience for big economic data releases. Expectations were for huge revenue and profit growth figures, and humungous they proved to be.

Nvidia stated that revenue for Q1 2024 will be about $24 billion versus predictions of about $21.9 billion on average. Q4 2023 revenue tripled to $22.1 billion (expected $20.4 billion) from a year ago, and profit after exceptionals was $5.16 per share (expected $4.40). The data centre division, the largest source of sales, was up 409% from the same period a year earlier. Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s founder and CEO, said: “Generative AI has kicked off a whole new investment cycle… Accelerated computing and generative AI have hit the tipping point”.

This will, in his opinion, lead to a doubling of the world’s data centres over the next five years and “represent an annual market opportunity in the hundreds of billions.”

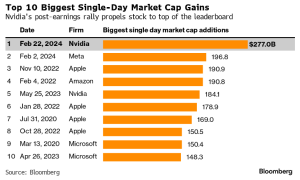

On the back of all this, Nvidia’s share price generated the single biggest one-day gain in absolute market capitalisation of any stock ever – see table below.

And yet, despite the short-term market-moving effect of it, this was probably not the most important corporate news of the week, at least in terms of the next phase of market activity. From our perspective, it was the flurry of merger and acquisition (M&A) news which tells us about a gradual shift in investment sentiment.

Here in the UK, electricals retailer Currys received a cash bid from the activist investor Elliott Partners. The 62p offer was 32% higher than the previous Friday’s close of 47p. The board rejected it and, subsequently, the Chinese retail internet platform JD.com said it would bid as well, although there are yet to be any details. JD.com is trying to get a foothold in UK retail web markets, and Currys presents an opportunity.

Meanwhile, in the US, credit card company Capital One announced an all-share agreed offer for another credit card and payment system company, Discover Financial Services. For Capital One, the value lies in combining its customer reach with Discover’s payment system, enabling it to compete with Visa and Mastercard. At $35 billion, this deal is substantially the largest this year, although it is not close to being in the top 10 of all time (a deal would have to top $100 billion to reach that accolade).

Nonetheless, last Tuesday’s announcement of the deal added value to both companies, with the total market cap rising from about $80 billion to $83 billion. It has slipped back a bit since then, with Discover shareholders happier than those with Capital One.

M&A goes on all the time, so what’s our point? Well, there has been a notable step-up in M&A activity coinciding with the recent market price rises. It appears companies are confident that waves created by the huge rocks of the pandemic, inflation and interest-rate moves are subsiding, meaning that business is stable enough for the near-term for them to look to the medium and long-term. They can see that a well-placed move might enhance investor views of their prospects and bring about a welcome increase in valuation multiples. In other words, investors will pay more for the shares because they expect stronger growth, because a bigger size will help beat off competition.

There is an inevitable consequence when intelligent folk realise that something is happening which they may not be able to explain fully. They stop saying why it shouldn’t be so and simply get on board. The boards of relatively large companies have noticed that being large isn’t enough. They need to be mega, or at least so big that the biggest won’t win everything.

And – different to the historical experience – the very largest have had stronger profit growth. One might argue that these companies are winners because they’ve proved themselves to be the best at growing, and that’s how they get to be the biggest over time. However, it also seems to be the case that being the biggest does confer the probable advantage of ‘owning’ the distribution platform. Businesses and consumers trust the outlets they know and don’t like to shop around too much.

M&A activity has interesting implications for us. Here at Cambridge, we are not in the business of picking particular shares (we leave that to the fund managers we select), so we’re not going to try to find bid targets. Rather, the potential buyers are doing what a classic stock picker does. They are trying to find an undervalued, under-recognised company and release value for itself.

From the start of last year, the largest stocks have been the winners, both in revenue and profit performance and in share price valuation terms; the multiples have risen for these ‘quality growth’ companies while they have languished for lesser companies. Now, rising M&A could mean that the ‘value factor’ starts to be valuable. Last week, despite the blow-out performance of Nvidia, mid- and small-cap stocks marginally outperformed.

The fly in the ointment is regulation. For example, the Competition and Markets Authority is yet to give its opinion on the Vodafone-Three merger deal announced in June last year. Expectations are for this to come at the end of 2024. Meanwhile the Capital One/Discover deal may get done more rapidly in the US, but will still not close until at least the end of this year; a long time and a lot of risk for shareholders.

That is not to say that ensuring a fair and competitive marketplace is wrong, but the process itself does pose some questions, for example:

- How can a regulator block companies from gaining the size to compete when it is unlikely to seek to reduce the size of their larger competitors?

- What should it do when large companies buy thousands of small early-stage companies?

- Should it step in when companies reach a huge size ‘organically’?

Still, as M&A activity rises, the likelihood is that investors will start to look for value. It will be enhanced substantially if buying companies feel that they want the targets with some cash, especially if they fund it with borrowing. That sends the message that interest rates are affordable.

The wait may be over and ‘Value’ may get a boost.

Uranium goes nuclear

There are huge adverts on hoardings across the UK for ‘Destination Nuclear’. Meanwhile, Uranium is in a

bull market. Are these things a coincidence?

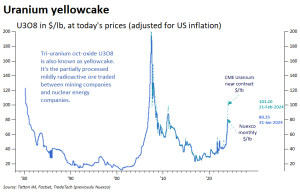

Spot prices for Triuranium octoxide – the partially-processed radioactive compound traded between miners and nuclear energy providers, also known as ‘yellowcake’ uranium – have shot up over the last few months. Yellowcake cost $87 per pound at the start of this year, rising to $103 at the time of writing. The metal compound really started heating up from August last year, but prices have been trending upward over the long term.

Uranium prices are more than four times where they were on the eve of the pandemic, and at comfortably the highest point in more than 16 years. If trading carries on like this, we will edge closer to the astonishing peak seen before the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. That is in nominal terms at least, but, as the chart below shows, yellowcake prices are still some way off that peak in inflation-adjusted terms.

It makes a stark contrast from years of relatively low prices. As the only source of fuel for nuclear fission reactors, uranium is and has long been a vital commodity. But until recently, nuclear power was often seen as a pretty boring investment – meeting ongoing demand but with little room for growth. The 2011 Fukushima power plant disaster in Japan added a lot of negative sentiment to the mix, with politicians and the public turning away from nuclear.

The situation is very different now. Nuclear power’s inevitable role in the global energy transition away

from fossil fuels is clearly acknowledged by politicians and, in many instances, is being backed up by strategy

and investment. At last year’s COP28 summit, 22 countries, including the US and UK, pledged to triple nuclear energy capacities by 2050. “The Declaration recognizes the key role of nuclear energy in achieving global net-zero greenhouse gas emissions”, according to the US Department of State.

Furthermore, it’s not just about transitioning existing electricity capacity. There is a link to the other current investment darlings, AI and electric vehicles, both of which are extremely power-hungry technologies. It may be possible to feed their huge future demands with carbon-neutral generation, but this requires substantial investment now.

The US and UK are building massive projects to revive their domestic nuclear production, but both are unfortunately facing setbacks; America’s Plant Vogtle is now likely to cost double its original price tag thanks to delays and complications, while Britain’s Hinkley Point C has been delayed until 2029 at the earliest, and costs have nearly tripled. But in a way, these bumps have only proved how committed governments are to their nuclear plans. Last week, EDF’s chief executive told the media he was confident of persuading the British government to finance two flagship reactor projects, after the energy company took a £13bn write- down on Hinkley Point C.

Perhaps more exciting for the industry are the plans to develop smaller modular reactors, such as those being discussed near EDF’s Heysham plant. These carry fewer risks or downsides (perhaps) than large plants, and their rollout is being talked up as revolutionary by some scientists and industry experts. In Britain’s case, the labour side of the nuclear equation is clearly being considered too – with the Destination Nuclear campaign looking to attract engineering graduates, recruit apprentices and retrain other workers for the nuclear energy industry.

This global structural push inevitably means more uranium demand, at least in the future. But it is hard to

account for the metal’s incredible price movement through near-term demand alone.

Shorter-term supply constraints are more pertinent for the current rise in prices. In particular, Kazatomprom – the largest uranium producer in the world – indicated on 1 February that it would struggle to meet production targets into next year due to sulphuric acid shortages and because of delayed new mine construction. Canadian producer Cameco also cut its production guidance.

Then there is the possibility that prices are increasingly being influenced by ‘fast’ investors. According to Tsvetana Paraskova of oilprice.com, utilities and miners formed 95% of the market in 2000. By 2011, they formed only 30-40% and that remained so until recently. The other 60+% are traders and financiers. Recently, because of increased hedge fund interest, Goldman Sachs, Macquarie and other investment banks have boosted their trading in physical uranium, futures and its options.

One of the reasons for the acceleration in price rises could be that fast investors are exploiting a weakness in the utilities companies’ contract setting. The utilities have tended to agree long-term contracts. The initial phase of nuclear power led to massive investment in uranium mining capacity which then met popular pushback, especially after the 1970s. As the previous graph shows, uranium prices collapsed and remained stagnant for a very long time. The bull run into 2008 still resulted in another extended decline.

Utility companies need assured steady supply so they fix longer-term contracts with producers. However, not all are at actual fixed prices. Some were fixed so that the supply was paid for at the point of delivery,

with the contract price at a premium to the spot price at the time of delivery. This made sense for utility companies expecting falling – rather than rising – prices going forward.

We think this may be a reason for the squeeze in prices. When prices rise rapidly and momentum dynamics take over, the deflation rationale behind the spot price plus premium contracts unravels and energy companies have an incentive to buy more uranium at current process to avoid paying even more in the future. This effectively creates a short squeeze on spot prices, and the effect is more pronounced because of fast investors’ large role in the market.

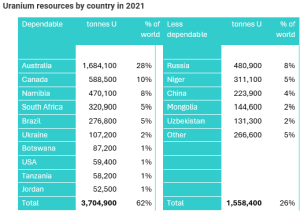

Fortunately, the potential physical supply of uranium – the amount it is actually possible to mine and enrich – is not a problem in the long term. There are plenty of mines and potential deposits throughout the world. Indeed, physical supplies are perhaps more diversified across regions than commodities like oil, gas and rare-earth metals.

Untapped ‘identified’ reserves in Canada, Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the US account for 50% of the total, according to the World Nuclear Association and the Uranium 2020 Red Book. Below is their data (world-nuclear.org) with our political classifications:

Identified resources recoverable (reasonably assured resources plus inferred resources), to $130/kg U, 1/1/19, from OECD NEA & IAEA, Uranium 2020: Resources, Production and Demand (‘Red Book’). The total recoverable identified resources to $260/kg U is 8.070 million tonnes U.

Moreover, the World Nuclear Association says: “The world’s present measured resources of uranium… are enough to last for about 90 years. This represents a higher level of assured resources than is normal for most minerals. Further exploration and higher prices will certainly, on the basis of present geological knowledge, yield further resources as present ones are used up.” Then there are huge quantities of currently uneconomical uranium present in ‘unconventional’ reserves, such as phosphate/phosphorite deposits and seawater. Essentially, the world has enough uranium to last hundreds of years, even with substantially increased demand.

However, near-term supply and demand is tighter, and geopolitics is clearly involved. Russia’s ARMZ bought Canada-based Uranium One in 2013, and China holds equity in mines in Niger, Namibia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Canada. Kazakhstan is currently the largest producer and is on a path to greater freedom, but that path also included asking Russia to be part of a force to counter a coup attempt in January last year.

Structural factors mean there is little reason why prices should have to go down in the short term, even at 16-year highs. But the fundamentals of the primary market should also limit how high it can go over the long term. We may see further increases, but these will inevitably come back as the weakly-positioned players clear their positions over the next year. Primary market participants might struggle with rapid price movements, but they should be able to adjust in time. Crucially, the uranium price squeeze is likely to be short term and will not stop the transition to nuclear energy – or the broader decarbonisation strategy of which it is a part.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.