Published

25th March 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –25th March 2024

Stick to the plan

The northern hemisphere has now entered the brighter half of the year, the days getting longer, lighter and warmer. Financial markets are also brightening. The past week has been good across the global board for equities and bonds.

The most obvious reason for the positivity (apart from the season) is that most of the world’s central banks are in a giving mood. Meetings were held here in the UK, and in the US, Japan, Switzerland and many other nations. The majority left rates unchanged but most indicated that rates are set to fall in the next few months.

Ahead of the Bank of England’s (BoE) Thursday meeting, traders were already pricing interest rate futures on the basis (they have ‘discounted’) that rate cuts would begin in in the late summer. Following the meeting, the traders brought forward the first cut to May or June. The reason was the dovish Governor Bailey, who told us in his press conference, and in a Financial Times interview, that “monetary policy has done its job”. In this case, he means that the Monetary Policy Committee has had a restrictive policy to combat inflation, and that “global shocks are unwinding and we are not seeing a lot of sticky persistence [in inflation] coming through at the moment”.

That allows them to pursue a less restrictive policy. Indeed, it ought to mean that they can move interest rates into line with economic activity. That probably means (in our calculation) rates of about 3.0% to 3.5% in around 18 months. Markets currently discount rates settling at 3.5% in 24 months’ time.

On the UK’s Monetary Policy Committee, the hawkish “external” members, Mann and Haskel, stopped asking for more rate rises, while the more dovish external member, Dhingra, continued to ask for a rate cut. The internal Bank of England (BoE) members remained voters for no change, but clearly the plan is that rate cuts will ensue as long as the growth and inflation data remain low.

Indeed, the speed with which inflation has declined suggests that inflationary behaviour has dissipated significantly. If businesses and consumers are faced with price rises, they buy less stuff. Encouragingly, retail sales data for February showed a slight rise in volume numbers of 0.2% from January. That was stronger than expected, but the consumer price inflation data was lower than expected. All in all, overall money being spent is rising slowly, rather than rapidly.

The BoE’s wait-and-see approach is coming to fruition. The hawks wanted higher rates, but if they had their way, we would have had a sharper slowdown and, probably, a longer recession. Currently the BoE has overseen the economy sliding into a mild recession in order to bring inflation into line, but one with gratifyingly few job cuts. And, as the increased dovishness shows, the bank now thinks persistently low growth is a greater risk than inflation staying too high.

The economy has some spare capacity and the FT’s interview with Governor Bailey suggests a lot of scope

for the internal members to vote for a cut by May, since year-on-year inflation should slip below 2% in April.

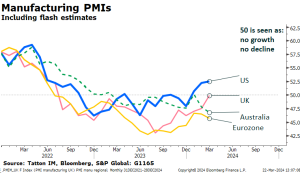

Europe also has spare capacity and could cut rates at the same time. The European Central Bank met at the start of the month, held its operational framework meetings the following week, and last week spread its message at the “ECB Watchers” conference that “rate cuts are coming”. March purchasing manager survey

data indicates that manufacturing has failed to sustain its slight bounce. The Eurozone manufacturing Purchasing Manufacturers Index (PMI), an indicator of business confidence, unexpectedly slid back to 45.7, as the chart below shows:

Services remain much stronger and jobs are not being cut noticeably but, as in the UK, inflationary behaviour is not evident, allowing inflation to decline. Switzerland also supported the idea of likely Eurozone rate cuts by unexpectedly cutting their short-term rate last week. The strong Swiss Franc is cited as the main reason, causing Swiss manufacturing to remain weak.

The Bank of Japan also delivered a dovish message. What is remarkable here is that they raised rates! We discuss this in one of the articles below.

China remains at the heart of global manufacturing weakness and a global disinflationary impetus. The hopes of a swift rebound have been supported by a mild upswing in commodity and energy prices, but other indicators are less positive. The Australian manufacturing PMI (which is heavily focused on mining and materials, shown in the chart) has also slipped back to the lowest level since the 2020 pandemic dip.

The Chinese offshore Renminbi fell in value last week, after a period of stabilisation. This has coincided with falling government bond yields and strong hints of more monetary policy action from the government.

Lastly, we turn to the most important central bank decision machine; the US Federal Reserve Open Markets Committee. Wednesday saw no change in rates, no change in the prepared statement, and Chairman Powell downplaying the recent uptick in inflation, saying, “It is still likely in most people’s view that we will achieve that confidence and there will be rate cuts.”

Commentators focused on the growing certainty of rate cuts, pointing out the fact that nine members expect three rate cuts in 2024, up from five in December, perhaps forgetting that the additional four had all expected more than three in December.

We did not expect a less hawkish tone from the FOMC. Although, at the margin, the economic expectations were a bit higher and the doves were less dovish, there is a growing confidence that the US economy is in balance. Manufacturing is stronger than in the rest of the world, but services confidence has eased amid signs of a jobs market that has become less ‘hot’. And, since import prices remain weak, the domestic economy can run a little stronger without causing a worrying resurgence in inflation.

So, Jerome Powell can stick to the plan, just as the other central banks appear to be doing. However…

The US economy has become stronger in the first weeks of this year, despite the stories of declining wage pressures. Unlike most other regions across the world, we think there is little spare capacity in the US, despite high levels of labour productivity (it may be that good productivity growth is because there are few available workers). US monetary policy is not restrictive in comparison to the current activity levels. The US may end 2024 in line with the Fed’s expectation of +2.1% real growth and inflation at 2.4%, but it will have to slow from current levels in order to do so. Current activity is rising rather than falling and now we estimate it to be at or above the 5.25%-5.5% Fed policy rate.

The central banks are rather revelling in a rare moment, when they can say they were right and everything is on track; economies are growing but not so much that inflation is going up (much), while jobs remain reasonably plentiful. They can say they saw it coming and they are going to stick to the plan.

Our caveat about policy is not a bearish one for markets either. If the Fed is a little lax, it should be good for profits in the near-term. We should only worry if inflation starts to move demonstrably higher and policy shifts from rate cuts to rate hikes. That’s not likely for some time.

Japan’s rates are up – and so are markets

In what for many is a once in lifetime event, the Bank of Japan has raised interest rates. In the 17 years since the central bank last delivered a hike, markets have endured a global financial crisis, a pandemic, a war in Europe and the assassination of Japan’s own former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has stayed firm through all that, but at long last the era of negative rates – dating back to a subzero cut in 2016 – is over. Governor Kazuo Ueda announced last Monday that Japanese rates will go up from -0.1% to a range between 0.0% and +0.1%.

These changes probably seem negligible to Britons whose borrowing costs have risen quickly and in large chunks. But, for the Japanese, the move is symbolic and significant. Having endured more than three decades of economic stagnation relative to other developed economies and its own past, the BoJ has been the only major central bank to maintain ultra-loose monetary policy, with no payout to Japanese bank deposit holders.

A change in policy had been strongly indicated ahead of the meeting. So, one might have expected little reaction from markets, but in the event there was a rather unintuitive response across domestic assets.

The value of the Yen fell sharply. Given that Japanese monetary policy is finally tightening, while US and European central banks are about to loosen, you would expect this to result in a strengthening Yen. Instead, the Yen has gone from ¥141 on the US dollar at the start of January to ¥151 last week. You might also have expected Japanese bond yields to rise – at least relative to the US and Europe, where monetary conditions are expected to ease. But Japan’s 10-year yields fell and are well below the near 1% peak from October.

Japanese equities rallied on the news, climbing last Monday and Tuesday after a flat performance the previous week. It was the resumption of an incredible rally in 2024, which has seen the Nikkei 225 jump more than 20% year-to-date. The Nikkei’s phenomenal figures are in part down to the weakness of the Yen, but Japanese equities have still outperformed all other major indices in sterling terms.

In summary, markets reacted as if the BoJ had cut rates instead of hiked. This is in large part because the policy shift was accompanied by dovish signals. Officials voted 7-2 in favour of a rate rise that Ueda signalled a year ago, but the governor gave no firm path for further hikes. Indeed, Ueda suggested that borrowing costs would not go up sharply as the BoJ is unsure whether inflation can remain at the 2% target.

Japanese inflation reached a peak of 4.3% last year after decades of deflation, but has already fallen back thanks to easing input price pressures – particularly from China. January’s prices were 2.2% higher than a year before, and economists predict this trend will continue to, or below, the central bank’s 2% mandate. To fight this stagnation, the BoJ is signalling a strong dovish bias, even if it needs to raise rates a little now.

Markets’ strong endorsement of Japan is a big help to the BoJ. International investors – ourselves included – are optimistic about the world’s third largest economy for both cyclical and structural reasons. Cyclically, the export-heavy economy should benefit from rebounding global (and particularly, Chinese) demand while businesses still have low financing costs, and exports are very cheap on a currency basis. Structurally, improvements in corporate governance, attitudes and profitability mean Japanese companies are ready to take advantage.

Last month, the Nikkei finally pushed past its peak achieved at the height of Japan’s asset bubble in 1989. The old record had haunted Japanese markets for decades, and its exorcism will help companies and investors psychologically. Back then, overinvestment meant Japanese products and labour were some of the most expensive in the world. Now, Japanese workers – among the world’s most skilled and highly educated – are substantially underpaid relative to the US. According to some estimates, output per hour costs half of what it does in the US.

Japan’s goods and services are, undeniably, extremely competitive. This has been the case for many years, but the last decade has been dedicated to improving old-school corporate governance structures, ensuring profitability and productivity for companies and ultimately raising wages. Prime Minister Fukio Kishida has been pressuring companies to pay their workers more, resulting in an expected wage rise of 4% for unionised workers – the biggest jump since 1992.

These deep structural and cultural improvements were the third arrow of “Abenomics”, and it is tragic that Shinzo Abe is not around to see his arrow land. Such deep reforms inevitably take a long time to have an effect, but we are clearly seeing that effect now. Thanks to these changes, the BoJ now believes it will be able to sustainably achieve its 2% inflation target – or close to it at least. Even if the longer-term inflation trend settled at 1.5%, that would be substantially better than before and, with nominal growth estimates of around 3%, it would mean a much brighter Japanese economy.

If long-term nominal growth levels were around that level, we would expect long-term interest rates, and bond yields, to similarly rise. And yet, bond yields remain below 1% and the BoJ appears nonchalant about further rate rises. This tells us the bank intends to keep rates below equilibrium, the rate which keeps growth and inflation in check. That effectively confirms the bank’s intention to keep monetary policy accommodative. Interest rates are likely to remain in negative real territory and substantially below overall economic activity.

This is the reverse of what we had seen for years, when the BoJ kept interest rates low in absolute terms, but punishingly high relative to underlying growth levels. It tells us the situation is perhaps more about background growth conditions than policy, but it is deeply encouraging nonetheless. For so long, the BoJ could do little in the face of stagnation. Now it refuses to do much in the face of inflation. Japan’s economy will surely benefit.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.