Published

29th July 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

29th July 2024

Don’t fear the rebalance

The rough patch for global stocks continues. Equities had a fairly dramatic fall last Wednesday, led yet again by the US large-caps. Wednesday saw both the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq experiencing their worst singleday losses since 2022, and the US volatility caused ripples around the world. Some of those aggregate losses were recovered on Thursday and Friday, after data showed that the US economy grew from March to June at a rate that had been well ahead of economist expectations.

Interestingly, for the third week running, the market positivity that ran counter to the overall trend was focused on smaller stocks. However, overall, it was not enough to counteract the value of mega-cap losses. But, sometimes, scraping off excesses is a healthy thing. Even though index-level returns look poor for last week, we think the underlying market rebalance is positive.

In the US, smaller companies caught a bid as Joe Biden’s problem with age became obvious following the first presidential debate. Comment was that smaller companies would be better supported by a Trump presidency, and that event had become a 70% likelihood in the political betting markets. But last week, following Biden’s exit from the race, his chances reckoned to have slipped somewhat, back to 60%, yet the smaller caps are still outperforming.

So, now markets appear not to be driven by a political narrative – instead it seems it’s about….

The not-so-magnificent seven

Just a few weeks ago, everyone was talking about the incredible performance of US tech giants, and how no other stocks could catch a break. But since July 10th, the Russell 2000 – the index for US small and midcaps – has gained nearly 10%, while the Magnificent 7 (Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Nivida, Tesla) have fallen more than 11%. After disappointing Q2 earnings reports from Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and Tesla, the Magnificent 7 dropped 6% during Wednesday trading alone.

Tesla was the worst offender, shedding 12% of its value after announcing a 33% slump in 2024 second quarter earnings (2Q24 versus 2Q23, analysts had expected a 26% decline). The electric carmaker is suffering from a double whammy: its sales are being hurt by the global downturn in automotives, while the shifting market sentiment on tech is hurting its share price. It is the only Magnificent 7 member to lose value this year (9.6% at the time of writing), but that has not insulated it from the recent tech downturn.

As both a tech company and an auto-manufacturer, Tesla’s struggles are symptomatic of the Chinese overproduction problem. Long story short, weakness in China’s domestic economy has led the government to stimulate production of export goods, particularly of electric vehicles. This has created an oversupply which has ended up being ‘dumped’ on international markets, pushing down prices. That is why global manufacturers – particularly carmakers – are in trouble, and there is a similar story with regards to microchip demand. We write about Chinese disinflation in a separate article.

No sign yet that manufacturing weakness will spread

Manufacturing PMIs (measuring business sentiment) were weak across most of the world in the latest data releases. Historically, weakness in the goods sector tends to feed through into services – as producers cut costs, which usually means weaker demand for services somewhere down the line. But manufacturers have been under pressure for a while and there are not many signs that this is significantly hurting the services sector in the western world.

Manufacturer problems seem largely to be about dealing with competition, since Chinese overproduction has hurt other producers’ pricing power. However, the demand side has held up reasonably well and lower prices are helping. US consumers have slowed the growth in spending but now prices are rising at a slower pace than that. Consumers also have more money available for services as the Service PMI also suggests.

Manufacturing pain does not seem to be a drag on the rest of the economy right now, but we must be wary of that changing. Equity valuations have already taken a hit from less positive company earnings outlooks, of which we saw a few last week. Capital expenditure intentions have recently been scaled back although actual spending has remained robust, perhaps because of the laggy timelines involved. Meanwhile, employment indicators have remained positive but if capital expenditure intentions are already reduced, any further cost-cutting could mean higher unemployment – which feeds back around into weaker demand.

A better distribution of wealth creation?

Potential cost-cutting and valuation adjustments are closely related to the tech stock losses. The dispersion from mega-caps to small caps is a healthy sign that the expansion of the economy is seen to broaden but, as we wrote last week, losses for the Magnificent 7 could still be painful. The sheer size of those companies means their losses often outweigh gains for others and, considering how heavily US citizens are invested in their stock market, confidence could be hit by a negative wealth effect.

Ultimately, though, the readjustment of capital from large to small companies will help growth prospects for small firms. When you combine this with an upcoming interest rate cut from the Federal Reserve, companies have a solid base from which to build. The case for long-term growth – not just in the US but globally – is not undermined by a few billion knocked off the Magnificent 7’s market value.

Interestingly, the UK is currently looking like one of the world’s bright spots – and recent business sentiment surveys were much better than elsewhere. Britain’s economy was already improving before the Labour government entered office, but the ‘quiet competence’ Keir Starmer has been trying to implement has certainly been well received by markets. Less fractious relations with the EU are by far the biggest benefit for investors’, and there is a sense that trading conditions are stable – or even likely to improve. Sterling strength is a testament to this, and that in itself gives the Bank of England more leeway to cut rates.

Markets have undoubtedly wobbled during the past week. As far as the US mega-caps go, unfortunately that wobble might not be over. But this is just the surface-level impact of what looks a genuine marketwide rebalance. Hopefully, that deeper process will move capital from where it was too concentrated to where could have the biggest growth benefits. Investors should not fear the rebalance.

China won’t ship out inflation

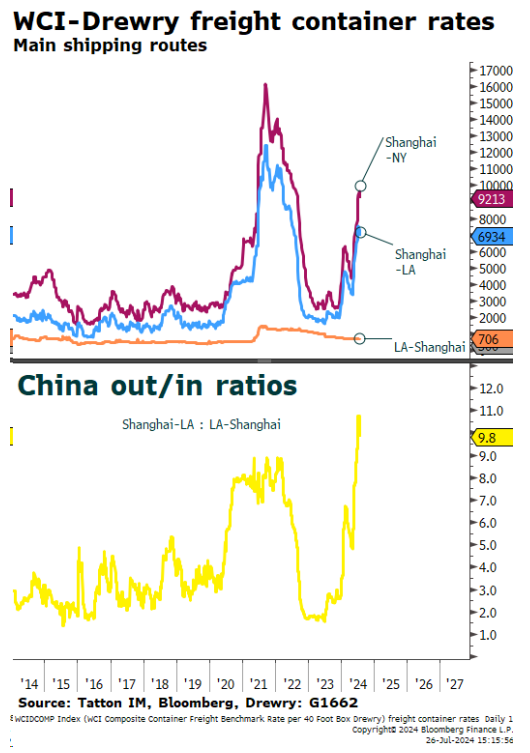

Consumers, investors and central bankers have felt collective relief this year at slowing global inflation. Recently, though, one historic predictor of global inflation has been moving sharply higher. Global shipping costs have increased dramatically in recent months. It now costs nearly $10,000 to ship a 40-foot freightliner of goods from Shanghai to New York – more than double the rate from the start of May. In the past, higher shipping prices have often led to downstream price hikes for goods and services. Does this mean we might see a return of global inflation at the end of this year or start of 2025?

Inflation usually ships out of Shanghai

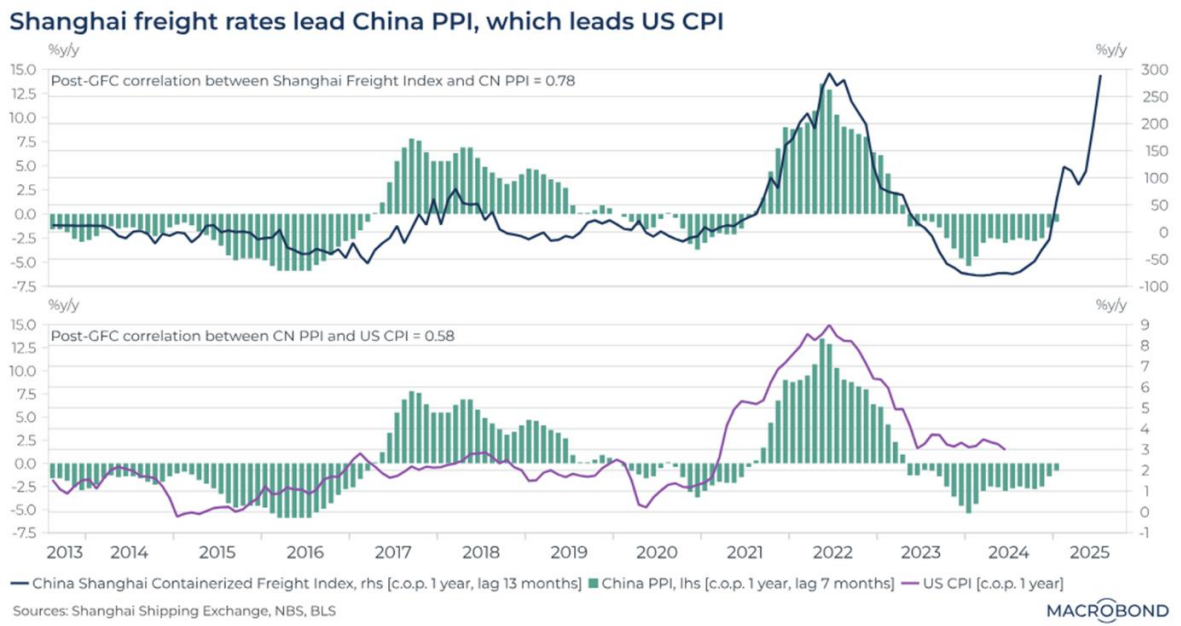

The chart below shows the relationship between Shanghai freight shipping rates, Chinese producer price inflation (PPI) and US CPI (Consumer price inflation) since 2013. The Shanghai freight and Chinese PPI changes are lagged (thirteen months and seven months, respectively) to line them up with current US inflation. As you can see, when shipping out of Shanghai becomes more expensive, Chinese producer costs go up, which eventually filter through into US inflation.

The explanation is fairly simple: shipping costs can be quite volatile and are usually the quickest to react to any supply-demand imbalances (as happened during the immense pandemic-era supply chain problems). As the world’s largest goods exporter, Chinese companies are sensitive to these costs – and prices in the rest of the world (particularly the US) are significantly impacted by the price of Chinese goods.

Indeed, weakness in Chinese PPI was one of the key factors pushing down global inflation over the last couple of years. China’s domestic economy has been weak for some time, but the government has been reluctant to stimulate private sector credit (as they did in the past), due to its long-term deleveraging goals. Beijing’s only other growth lever is stimulating production, but pulling that has resulted in an oversupply of goods, which China then ships out to the world. In other words, global goods disinflation over the past couple of years was a Chinese export.

This time, freight costs look political

The sharp increase in Shanghai freight rates is alarming because it looks like that process could play out in reverse – just when we thought the global inflation spike was beaten. Some commentators and analysts have been looking for the usual supply chain problems to back up this narrative, which are never too hard to find. However, we believe the story is different this time.

While some disruptions can be found, what seems to be pushing up freight rates this time is a massive pickup in demand for shipping out of China. As you can see in the chart, prices for freight out of Shanghai – particularly to the US – have jumped massively higher than freight prices in the other direction. In other words, firms seem to be in a big rush to buy Chinese goods.

As for why US businesses might be in a hurry to load up on Chinese exports, the elephant in the room is Donald Trump. The former president’s trade wars against China opened a new chapter in Washington’s relationship with Beijing and, while Joe Biden has continued and expanded the fight, Trump has promised to erect significantly higher trade barriers between the world’s two largest economies if re-elected in November. The Republican candidate said earlier this month that his administration would consider tariffs of 60% or higher on Chinese goods.

The odds of a second Trump presidency have soared in recent months. They have come down somewhat following Biden’s campaign exit and the presumed Democratic nomination of Vice President Kamala Harris, but markets are still firmly in the Trump preparation mindset. That extends to Chinese exporters and US importers, who might see the next few months as the last realistic chance to exchange goods at acceptable terms. That means we should expect goods to continue flowing from China to the US until the end of the year, even if freight costs seem prohibitive.

China is in no position to put up prices

Of course, freight prices can still have an inflationary impact if they are going up on political fears. But that would require Chinese exporters putting up their prices and, crucially, US importers buying the goods anyway. Given China’s weak domestic economy, manufacturers simply do not have the power to do so. They are still working through inventory overhangs, and most are unable to do anything except bear the cost of shipping themselves.

This matches up with what we are seeing from manufacturers around the world. The latest manufacturing sentiment surveys are weak across most major economies (with the UK being a notable exception), a continuation of a long-term trend. With global (mostly US) demand surprisingly strong for much of this year, you would expect inventory kinks to have been ironed out, and a turnaround in goods disinflation. That this has not happened is a sign of China’s huge overproduction problem. If Trump is re-elected and hikes tariffs as expected, that would bring its own inflation pressures for US consumers – but these might be counteracted by sharply weaker demand for Chinese goods. If Trump unexpectedly loses – or is lighter on China than his current rhetoric – the readjustment could push down freight activity too. Either way, freight costs themselves do not look as inflationary as in the past.

DISCLAIMER

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.