Published

22nd April 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –22nd April 2024

Market quiet on the Middle Eastern front

The Middle East is dominating world news again, as the awful moment has come when Israel and Iran have engaged in open and direct conflict, albeit at great distance. That the warfare is across considerable distances makes it different to close conflicts like the Ukraine war, and introduces a clear danger that war could spread across the Middle East – a region that is still of great importance to the global economies’ oil supply.

However, currently neither side has a quick-win strategy or indeed any interest in deepening the conflict. It appears that Iran and Israel have reached a point where punctuated aerial attacks are likely to be the maximum level of conflict. Mistakes are possible and Gaza and the West Bank still remain the focus of Israeli attention, and Israeli public support. Gaza’s population is in a dire condition and remains the greatest issue. Israel feels that it must remove the ongoing threat, but can only make slow progress. Even then, the cost is dreadful and causes terrible suffering.

Israel’s allies are much more powerful and committed than those of Iran, but do not want any expansion of the conflict. Iran’s regime is weak in many ways, especially in its popular support. While war can be a means of bolstering support, it is not likely to be effective for most Iranians.

The acts of the past week might not be described as the opening shots in a full-scale conflict but, according to some observers, they were designed to be ineffective, indicating powerfulness but causing little actual damage or loss of civilian life. The retaliations assuaged internal critics but were designed to make sure external parties remained uninvolved. In a sense, therefore, the actions from both sides in the past days offer more hope than concern.

Inevitably, it is our job to consider what effects the conflict has on investments and markets. It may surprise readers that the market downdraft we have experienced for the last few weeks was only partially influenced by the hostilities in the Middle East, and the risks to global oil supplies that these bring.

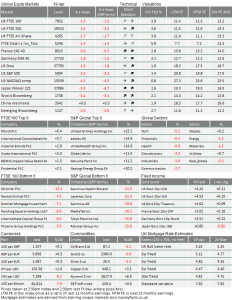

Throughout the course of last week, the US dollar strengthened, and equity markets weakened again, showing that investors’ risk appetites have ebbed. This is because a broad range of factors have changed, compared to the more upbeat first quarter of the year. Perhaps unsurprisingly therefore, the assets most under pressure are the best performers year-to-date, suggesting that investors are keen to book profits. Japan’s Nikkei 225 Index fell the most among the majors, -6% in Sterling terms, having still been the outperformer the previous week. Tech stocks were also hit hardest among sectors, with Apple having fallen 6% on fears about Chinese sales and Tesla continuing its very poor run, down 12%, despite announcing a major cost cutting plan.

In currencies, the Mexican Peso fell back 5% against the US dollar following its very strong run. We write about the Peso’s background below and what it tells us about changing investment opportunities beyond the economies of the G7 group of nations. Major currencies like Sterling, Euro and Yen were only slightly weaker, but notably remained stable when Israel’s alleged retaliation strike on Iran occurred on Friday.

Government bond yields went higher (and so bond prices were lower) during the first half of last week, after Iran’s drone and missile strikes. However, it was notable that real yields – i.e. what remains of bond yields after subtracting the expected rate of inflation – did not move much. The exception was in the US, where real yields almost matched the rise in nominal bond yields.

One might have expected oil prices to surge, but the pricing of Brent crude oil futures has been very stop start. Brent hit a high of $92 per barrel last Friday morning, before slipping again as they did on each day last week, despite or perhaps because of the news from the Middle East, as we discussed above.

Risk appetite and growth optimism are strongly linked together, one might draw a theoretical distinction but it’s almost impossible to distinguish in practice. Weaker markets clearly suggest that investors’ growth optimism has shrunk in the past few days. That almost certainly has to do with changing expectation about near-term interest rate cuts, and how these may influence both bond yields and global growth this year.

We noted in the past couple of weeks that stubborn inflation pressures were putting central bank decision makers under pressure to become less dovish, and Jerome Powell duly delivered that message last Monday. While he did not say that rates might go up, he indicated that they would probably have to wait longer for the first rate cut than previously expected.

Interestingly, Andrew Bailey was faced with similar questions last week after the higher-than-expected UK inflation data (at 3.2% year-on-year for March, versus expected 3.1%). He chose to downplay this, appearing mildly dovish. Investors still expect a rate cut in late summer and Bailey made it clear that we wouldn’t necessarily have to wait for the US to act.

Bond markets appear to be in a bit of a dilemma. Inflation is potentially more embedded than thought. Yields rose over the first quarter because both inflation and growth dynamics were stronger than expected, especially in the US. Now, expectations of growth are being challenged and bond investors are having to discount the possibility of relatively tighter policy, at least for the short term.

Still, it seems the biggest change is coming in risk markets. Higher bond yields may reduce growth expectations, but the biggest issue is that equity analysts have already forecast strong enough growth to generate a 10% jump in S&P 500 earnings per share in a year’s time. The external risks challenge that optimistic outlook.

And, investors have been even more optimistic than the analysts, pushing the price-to-earnings ratio valuation on those optimistic analyst forecasts up to historically expensive levels. Last week, the ratio has actually fallen to 20x from the above 21x level seen at the start of the month. Nevertheless, the 10-year average is 18x.

The recent tendency for investors to back trends also seems to be adding to the current picture. Trend- following funds were active last week, but this time selling rather than buying. These types of funds are much more prevalent in the US, and that’s adding to the volatility and rising sense of risk.

Worrying about overoptimism does not mean we should give up on optimism about the medium-to-long- term picture, given the risk and expectations of meaningful recession have all but disappeared. The current volatility is very normal, indeed more usual than the unremitting daily gains of the earlier part of the year. Markets may well get less expensive relative to expected earnings, but that doesn’t mean earnings will fall.

In fact, it may well be that a little less exuberance in markets could help reduce inflation expectations more broadly. That should help central bankers get back to thinking about cutting rates. And then, the rate driven growth cycle can begin again.

Mexican peso going strong

The strength of the US dollar has attracted media attention in recent weeks. The world’s reserve currency is usually considered a ‘safe haven’ asset, so its strength is sometimes taken as a sign of global geopolitical nerves – of which there are plenty right now. In actual fact, the dollar has been strong for quite a while, particularly against the stereotypically riskier currencies of Emerging Markets (EMs). EM currencies have struggled against the dollar through the latest cycle of interest rate hikes – since higher risk-free rates cause global investors to pile money back into the world’s largest economy. But even before that, the prolonged period of US growth outperformance was hard on EMs.

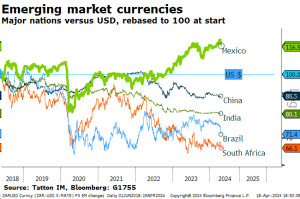

The chart above shows the performance of some key EM currencies against the dollar over the last seven years. All but one of them has depreciated substantially – or collapsed, as in the Turkish Lira (which we don’t show because it makes all the other currency moves look tiny). The Mexican Peso stands out as the only currency to gain against the dollar since 2017. Perhaps more impressively, since the US Federal Reserve started hiking interest rates just over two years ago, Mexico’s currency has appreciated around 20% against the US dollar – outperforming other EMs by some distance.

Mexico’s domestic policies have played a big part in this strength. When President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (nicknamed AMLO) came to power six years ago, there were concerns that the avowed leftist would wrack up debts and sink the currency value in the style of previous Latin American leaders. But, as we approach the end of the President’s six-year term, it is almost certain that AMLO will be the only Mexican leader in modern history to leave office with a stronger peso than he inherited.

AMLO specifically targeted a stronger peso and should be commended for achieving it, with help from the Bank of Mexico. The central bank raised interest rates hard and fast when global inflation began to build in 2021 – long before developed nation central banks joined in. This swift response boosted the interest rate differentials between the US and Mexico, driving capital from the former to the latter.

Even when the Fed started raising rates – virtually a full year after the Bank of Mexico – Mexican rates finished the latest rate hike cycle 7.25 percentages higher than they began, compared to the 5.25 percentage point cumulative hike in the US. That differential increased the attractiveness of the ‘carry trade’, where investors borrow money from a low-rate region and invest it in a high-rate region. Data suggests that the US-to-Mexico capital flows have been particularly strong in recent years, bolstering the currency.

That brings us to perhaps a major factor behind the peso’s strength. Several Latin American countries raised rates high and early, but did not receive the same “carry trade” flows from investors. Unlike its neighbours, Mexico has always been a huge trading partner for the US, and these trade flows have grown substantially in recent years.

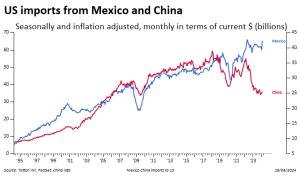

Last year, US-Mexico trade surged past $798 billion, making the US’ southern neighbour officially its biggest trading partner. The country it surpassed was China, whose relationship with the US has soured in recent years. Political tensions between the world’s two largest economies have been rising for years, but it is now clear that this is having an impact on where companies base their operations, or which foreign firms they trade with.

Data and anecdotal evidence suggest that manufacturers with significant US sales are keen to produce closer to the US and further from China. This so-called nearshoring was an explicit goal of Donald Trump’s anti- China policies. President Biden has continued, and in many cases expanded, these policies. It is also clear that, despite Trump’s anti-Mexico rhetoric, those south of the border have benefitted dramatically from this US reallocation.

This has been a structural force pushing up the peso, but flows were bolstered by the cyclical forces described above and now those cyclical forces arguably have little room to run much further. Last month, the Bank of Mexico cut interest rates. Joining a host of other Latin American central banks who hiked hard and fast during the pandemic, were successful in bringing down inflation, and now have space to breathe. That is good news for the domestic economy, but it could reverse the carry trade flows until US rates are cut.

Mexico will have a new president after its June elections, as the constitution prohibits AMLO from running again. His party’s successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, is extremely likely to win, and has been publicly supportive of the president’s strong peso policy. Her nearest challenger criticises the peso’s strength, though, arguing that it harms Mexico’s exporters. It is possible that, behind closed doors, she might agree. Even if she does not try to actively weaken the peso, it would be a bold decision to try strengthening it further – especially considering the recent declines in economic activity.

In terms of purchasing power parity, the peso is the strongest against the dollar it has been for many years. We might think that limits how much higher it can go – particularly considering the cyclical factors mentioned above. On the other hand, we could see this as a sign of how strong the structural boost to US-Mexico trade has been. We have every reason to think this will continue. Mexicans stand to benefit – especially if the US economy continues to outperform.

This realignment of global trade changes could change how investors think about global growth – and EMs in particular. For years, US-China flows were the key ones to watch for global growth, but global trade is now much more fragmented. Increasingly, we need to look at a broad variety of trade relationship to get a sense of what is going on and where the investment opportunities of the future may be.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.