Published

20th November 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –20th November 2023

Inflation genie back in the bottle?

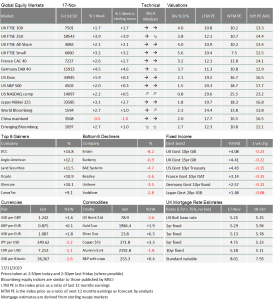

Last week was another good one for most investors. In sterling terms, the strongest equity markets were in Europe with the DAX up 4.5% since last Friday afternoon. The biggest winners have been small and mid- sized firms; the UK Mid-Cap index has stormed up by 4.3% compared to a 1.4% increase for the UK Large- Cap index. Likewise, the Russell 2000 (America’s most-watched market index for small and mid-sized companies) is up 5.1% in US dollar terms.

As we reasoned the previous week, risk asset markets are benefitting from the perception that central banks have reached their tightest levels in terms of interest rates and the most likely next moves now are lower. That perception grew stronger this week. Yields on 10-year government bonds are down another 0.2%-0.3% in the UK, Europe and the US. The move is even stronger for shorter-dated maturities.

Monetary policy tightness has had a greater impact on smaller firms as they have less ability to directly issue fixed-coupon debt funding in the major bond markets but rely on banks and other lending institutions. The inverted yield curves in longer bonds (yields on longer maturities are lower than those where funds are locked up for less long) may signal that investors expect rates to fall at some point, but smaller firms gain no benefit from that view because their financing tends to be on shorter terms than what big companies can achieve through bond issuance of their own. Investor cash and lower funding rates in this phase thus gets channelled to larger firms. However, in the phase where the curve inverts at the short end, this can send a different signal.

The chart above shows how 2-year rates have fallen in the period since the last round of central bank meetings. The pace of those falls picked up last week. As a result, investors are starting to feel smaller companies may get a break in the foreseeable future, and start winning rather than losing, relative to larger sized firms.

Thinking we are through the worst is tempting but is also dangerous. Indeed, central banks moving from tight to easy is also a sign that economic growth is not going so well. And if growth is not going so well, profits may be under pressure.

That seems to be the case for the Russell 2000 companies. Analysts have been digesting the latest earnings reports together with managements’ future guidance and revising their projections for the tail-end of this year and for 2024. It is not unusual for them to revise down the last bit of the current year’s numbers, but they usually remain reasonably upbeat for the next. This year though, there has been a more noticeable wave of pessimism for 2024 than one could reasonably expect due to seasonality.

One of the interesting aspects of the global fall-back in inflation is the disparity between goods and service prices. For producers of things, pricing power seems to be hard to come by of late. Businesses have been trying to reduce overstocked inventory levels but final demand has been slowing faster than they can manage inventory levels down. This week, the data showed that US producer final-demand price growth slipped to a 0.5% month-on-month fall in October. They had been stronger in the summer but this reversal is significant. US industrial production fell quite sharply, by 0.6%, and factory utilisation rates declined to 78.9%, the weakest level since September 2021, while US inventory levels were reported earlier this month as still rising. A similar dynamic occurred in the UK, although October’s output prices managed a small 0.1% rise rather than a fall.

Last Thursday’s sluggish stock market price action suggested investors are struggling with this dilemma as they digested these latest data updates. Perhaps growth is in a short-term soft patch and will bounce back given that employment levels remain resolutely strong. But it is also currently soft enough to be creating cashflow problems for some firms, judging by the recent increase in default rates.

We have one more set of 2023 central bank meetings in December. Investors have been positive about prospects of dovish announcements, but we will need to hear that it’s more than okay to talk about rate cuts – which the previous week was certainly opposite to what central bankers stressed.

On the political side, China’s President Xi sounded distinctly dovish in his meeting with US President Biden. Biden appeared to make an error, describing Xi as a dictator (although one might think this ‘slip’ was more about playing to a particular subset of the US audience) but nothing was made of it by the Chinese.

We write about China’s policies and economy in the second article below. A significant factor in global goods price falls is China’s past overproduction and current soft private sector demand. The increased urgency to revive economic growth that China’s leadership is currently displaying – on both monetary and fiscal fronts – suggests that their weakness is substantial and probably spreading across the world.

The good news is that policy action is unmistakeable. We may be wary about its efficacy but it is happening. China’s equity markets appear especially wary but they may be ripe for a bounce similar to that seen in small and mid-cap stocks in the West.

Lastly, the US dollar has weakened as the US growth exceptionalism appears to be running out. We think that this has the makings of an important shift, one which could be important for longer-term economic and investment outcomes. We will cover this in our 2024 outlook which we intend to publish in mid-December.

Global economic round-up

One year ago, high levels of inflation were the greatest concern for investors and policymakers. For much of this year, the pace of price rises has declined but in order to achieve this, central banks have raised interest rates to cool down demand and so the world’s economy has slowed. That slowing has done its job, with an increasing impact on inflation.

As the chart above shows, service prices have slowed but remain relatively elevated. However, goods prices have moved into actual deflation. Now, the fragility of global growth is a greater concern for investors than the possibility of another bounce in inflation.

We know that if policymakers want to guide demand in their economies, they face a very difficult task. Policy changes have many impacts, but they only become visible months or even years afterwards. And, because the links in an economy can change a lot, the degree and time they take also varies. It also takes time to assess what has happened.

We know where things were a few months ago, but getting a good grasp on the current state of the world economy is always challenging. Even the most up-to-date gross domestic product (GDP) figures are about three months old since they are inherently backward looking. Data is collected from many sources in old- fashioned methods, then painstakingly reviewed and calculated. Central banks always pronounce they are data-dependent but, as we wrote last week, being ‘authoritative’ can mean being dreadfully behind the curve.

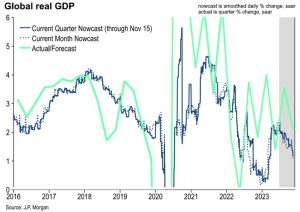

Analysts such as those at JP Morgan (JPM) try to overcome these problems with their ‘nowcast’ – estimates of how key economic indicators are doing right now based on disparate and more modern sources. Those analysts have been applying these techniques across the world to give a more consistent and detailed view.

So, as we come to the end of 2023, where do they think we are now? Which regions and which countries are holding up best?

In aggregate, JPM analysts think global growth (on an inflation-adjusted or ‘real’ basis) is currently running around an annualised rate of +1.4%, having come down from just above 2% in the summer. One thing to note is that this number is a smoothed ‘current rate of change’, and is not a calculation of the change from 12 months ago:

For each region and country, to see how ‘hot’ an economy is, it’s important to see how their growth compares to their ‘potential’ or optimal growth rate. Central banks pay close attention to potential GDP, but as much as a somewhat abstract and unobservable measure as it is an important one. An economy’s potential at any given point is what its GDP would be were labour and capital used to their maximum sustainable level – where sustainable means keeping inflation within central bank targets. The gap between real and potential activity is called the output gap, estimates of which are key to monetary policy. Economies with positive output gaps have more demand than available supply, and hence are at risk of overheating. Those with negative output gaps are essentially experiencing a shortfall in demand and (usually) high unemployment.

The current situation is therefore a little unusual. By JPM’s measure, the global economy in aggregate, and most of its economies individually, are growing slowly, below its assessment of potential growth. This is despite unemployment rates that would generally indicate a shortage of employee resources. It could imply that potential growth is lower than previously thought, or merely that the labour market is slower to adjust to the new macro environment.

Notable exceptions to this are China and Russia, with both appearing to be running above potential, according to JPM. That is somewhat surprising in China’s case, given that year-on-year price deflation since deflation is what we expect if growth is substantially below potential (by definition!). We discuss this more in a separate article.

Russia’s growth is also somewhat surprising, and probably concerning for the supporters of Ukraine. Russia is clearly benefitting from an oil price that has been sustained at a relatively high level (it has fallen in recent days but this is too soon to affect even the nowcast growth indicators) Moreover, Russia appears to have benefitted from a reduced discount from benchmark oil prices, and is finding more buyers prepared to risk the ire of the West. Strong growth in Russia (estimated at 5% by JPM) lessens the pressure on Moscow and hence could well make war and disruption more likely to continue.

At the other end of the scale, the UK was significantly below potential at the start of this year and has since moderated – though without ever climbing above potential. Europe, meanwhile, has kept a steadily negative output gap through most of 2023, though lately has fallen significantly below potential. And yet, both the Bank of England (BoE) and the European Central Bank (ECB) have kept pushing up interest rates and talking of sustained monetary tightness. In one sense this shows how misleading estimates of the output gap can be in extraordinary times like these; British inflation was running at double figures when it was operating below potential, and core inflation (excluding volatile items like food and energy) has kept rising throughout the year.

Equally though, these stark comparisons show how extraordinary conditions have been in the post- pandemic world and, crucially, hint at how policy might change if and when we get back to the old normal. Central bankers were undoubtedly caught out by how sharp and persistent inflation has been over the last two years, and the current aggressive messaging is in part a reaction to being behind the curve for so long. As many commentators have pointed out though, being behind the curve on the other side – crushing growth unnecessarily – is just as embarrassing. It could be even worse for developed world central bankers if they are accused of punishing workers without cause.

If economies continue to drift below potential and the pace of inflation continues to move down in developed nations, ‘higher’ won’t be for ‘longer’. However, we would remind everyone that not taking monetary policymakers at their words has been a losing game all year long.

Caution should particularly be taken with the US Federal Reserve (Fed). The Fed is in many ways the leader of the ‘higher for longer’ chorus, because the US economy is leading the developed world. According to JPM, for example, US growth dipped only mildly below potential into the end of 2022, then bounced back to record a blistering 4.9% seasonally adjusted annual rate from July to September, obviously above potential. Over only a few weeks, growth has now shifted back below a 2% potential estimate. Unemployment has risen slightly to 3.9% but is still below the Fed’s 4.5% estimate of employment balance.

So, while there is some logic to expecting rate cuts from the BoE and ECB, expecting them from the Fed – as many now are – looks riskier. Moreover, the whole picture is complicated by the fact that developed-world central bankers take their cues from each – and so often particularly from the Fed. It may take yet more weakness and fragility to really change their minds.

China begins to realise its potential

For western investors, China is the biggest disappointment of the year. A post-Covid boom looked like a sure thing 12 months ago, but economic activity has been lacklustre, held back by an ailing property sector and weak domestic demand. While most developed economies have struggled to contain sky-high inflation, China has been flirting with deflation all through 2023. Accordingly, the stock market rally into the end of last year has well and truly unravelled. A consistent slide from January leaves mainland China’s benchmark CSI 300 index barely above where it was in October 2022 – its lowest point during the entire pandemic.

One of the biggest factors behind the slide into pessimism this year has been the evidence that China’s leadership have wanted to support the economy but will not allow it to exacerbate perceived structural weaknesses – as they did with previous rounds of economic stimulus packages. The policy priorities have led to many policy support measures to be instituted, but which have no follow-through because the usual transmission routes have been blocked. Beijing excited markets last year when it hinted at monetary and fiscal easing – supposedly aimed at stressed property developers – but actual measures have been relatively moderate and, at times, have been hampered by other barriers which have been outright restrictive.

That follow-through is sometimes referred to as the ‘multiplier’ effect, where government outlays improve corporate profits and wages, which lead to further spending and investment by those companies and households. Economic activity has risen but unfortunately corporate profits have been lower than expected. This is a far cry from previous episodes, most notably in 2015, when Xi Jinping’s government wielded its policy ‘bazooka’ to turbocharge the economy.

However, things could be turning in the world’s second-largest economy. Chinese consumer demand and industrial activity both came in stronger than economists expected in October. Retail sales showed 7.6% year-on-year growth last month, beating expectations of 7% and comfortably above the 5.5% figure from September. Industrial production was more muted but showed marginal improvement on the month before, 4.6% for October versus 4.5% for September – and was the sector’s strongest return since April.

After repeated disappointments, investors have stopped waiting for the bazooka to come back. And yet, this week we have seen the clearest signs of increased firepower. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) gave out RMB 1.45 trillion through its medium-term lending facility, smashing expectations of RMB 950 billion. Minus expiring funds, it meant a net injection of RMB 600 billion, the central bank’s biggest splurge since the heady days of 2016.

Just as encouraging is a potentially powerful fiscal boost. According to Bloomberg, Beijing is considering giving up to RMB 1trillion for urban village redevelopment – most likely through its pledged supplementary lending (PSL). The PBoC uses PSL to give banks loans which are then redistributed to sectors that need them. The sector most in need is clearly property development, which has teetered on the verge of crisis ever since Evergrande’s not-quite-collapse years ago. Urban development and construction would go somewhere to repairing the sector – which has weighed on wider consumer and business sentiment – as well as directly supporting demand.

Both of these moves – and particularly the PSL expansion – look a lot more like 2015’s than 2023’s. We suspect this is deliberate. Beijing’s subdued response to economic weakness over the last few years is a part of its longer-term plan to deleverage the economy and move away from the debt-fuelled growth model which dominated policy for decades. Compressing growth is, in a sense, part of the plan – but Xi knows he can only compress so much. The throwback to 2015 policy – the zenith of Beijing’s credit-growth model – is likely in part to appease those nostalgic for the good old days.

Repeating old policy does not guarantee the same old results, of course. It is encouraging that real growth is reasonably strong and likely to improve, but substantial disappointment since 2020 suggests neither households nor investors will suddenly become optimistic. While certain signs are good, others are not – including worsening consumer and producer price deflation figures published just the previous week. China has been running at a decent growth rate in real terms, but nominal growth is still historically weak.

Support for building companies should give a boost, but this is unlikely to be immediate. It is more likely that the overall growth figures for 2023 will still come in below the lofty hopes of one year ago, and the start of 2024 might not be much better. The growth outlook – updated in response to Beijing’s newfound resolve – looks good for later in the year though. Morgan Stanley estimate the fiscal boost will add 1.5% to GDP in 2024 overall, which comes on top of already decent growth figures.

The government is clearly alive to how weak China’s economy has been and will know that rebuilding confidence will take time. This is no doubt one of the reasons for President Xi’s conciliatory approach to the US, exemplified by meeting President Biden in San Francisco this week. While concrete policies rarely come from such high-level meetings, it is an undeniable show of China’s willingness to normalise US relations after the tensions of the last few years. What that means for the Chinese, American and global economies depends on whether Washington feels the same. On that front, it will help negotiations that Taiwan’s opposition leaders – more open to dialogue with China than President Tsai Ing-Wen – have joined forces for the upcoming election. All involved will want things to stay cool across the strait of Taiwan.

As we wrote recently, economic positivity does not ensure decent asset returns – as China has exemplified for decades. It is telling that the mainland CSI 300 and Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index have not responded to Beijing’s policy moves yet and are still stuck in their ruts. There are many reasons for this, with anaemic profit growth chief among them. However, one factor is probably the lack of liquidity in Chinese markets (particularly after western investors dumped China en masse this year). It is possible that liquidity injections from the PBoC could help to enable markets to connect to an improving economy.

In that case, Chinese stocks could start to look attractive. Chinese companies have endured a long period of selling and, in some cases, have already lost much of their foreign-linked backing. Strong growth and ample liquidity are a potent mix in these cases. We have to be very tentative of course, as China has a long list of potential deterrents to market sentiment. But the upside is simple enough to see. It is really just the typical sentiment cycle. As usual in capital markets, excitement breeds disappointment, but disappointment breeds opportunity. China has gone through the first stage; let’s see if it manages the second.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.