Published

20th May 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

Pluses and minuses

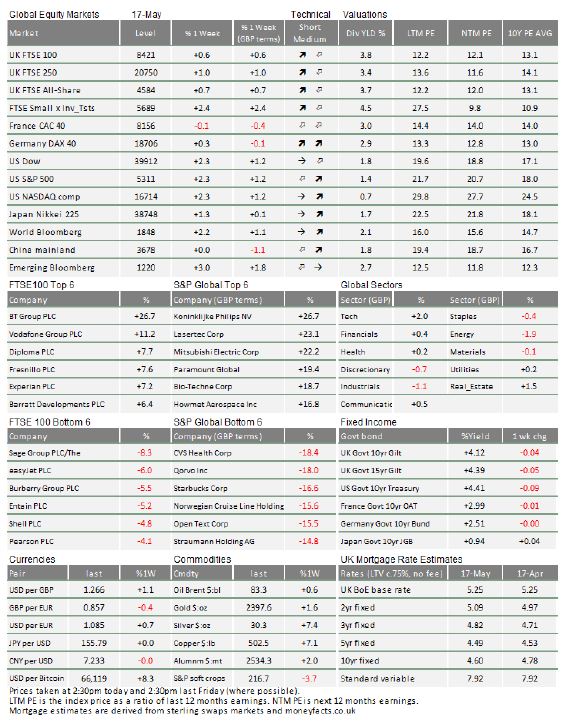

It has been a decent week for investors, with global stocks up around 1% from last Monday. British and European equities finished virtually flat, with the US and China slightly up. The gain for US stocks was not outsized, but it was enough to take the S&P 500 to a fresh all-time high last Wednesday. Breaking that record made a fairly average week for markets look like a great one.

US stocks were able to break fresh ground because of encouraging inflation numbers published last Wednesday. April’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) report showed a 3.4% increase on the year before, exactly in line with economists’ expectations. Not particularly outstanding, one might think, compared to the EU and UK, which are fast heading down towards 2%. But it meant slower inflation than the month before for the first time this year, and the first time this year that US inflation did not exceed forecasts. With the inflation outlook finally improving, investors piled into US stocks in the aftermath, sending the S&P 1.2% higher on the day. Markets have become so used to the US economy beating expectations that it feels like an achievement when things are as predicted.

Tamer inflation numbers increase the likelihood of an interest rate cut from the US Federal Reserve, which would support relative equity valuations and offer relief to borrowers struggling under the weight of the increased interest burden. Markets have been excited about the monetary policy pivot since late last year, but continued strength in the world’s largest economy has repeatedly pushed back the timeline for cuts. Four months of higher than forecast inflation – together with a still-tight labour market – have led some to question whether cuts are coming at all. Disinflation signals are therefore crucial support for market sentiment right now.

Still, when we look at the detail, we cannot get too excited about US inflation. While CPI was in line with expectations, producer prices beat the forecast once again. This shows that companies still have pricing power, and that usually indicates higher consumer prices down the line. This matches up with the other signals too: consumer demand has been handsomely strong even as the labour market loosens, and recent corporate earnings show that companies are still very profitable and expect to improve their earnings further.

These mixed signals present a conundrum. For most of the year, markets were propelled by rate cut expectations – which were themselves predicated on falling inflation – while growth or at least growth expectations maintained a healthy upward pace. Persistent inflation on the back of that growth dashed some of those hopes and led to the first real bout of volatility last month, as growth finally slowed somewhat even though broader growth data showed there is still plenty to get excited about. Moreover, the Fed keeps hinting that cuts will come despite inflation still comfortably above the official 2% target.

There is a growing feeling that the vibrant US economy simply has more inherent inflation pressures than before the pandemic – but without this necessarily affecting economic stability or investment. It currently comes with higher growth and stronger corporate earnings, which could just result in price stability at a higher level, rather than instability. If so, it is debatable whether the central bank’s official 2% inflation target is still appropriate.

By contrast, rate cuts look a sure thing in Europe and the UK. Inflation has come down significantly this side of the Atlantic, and this is ultimately related to weaker growth prospects. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) both have greater room to cut rates and more of a need to, with support required as economies come out of last year’s technical recession.

While rate cuts seem certain, how deep or fast those cuts will be is still an open question. Recently, ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel warned that back-to-back cuts are unlikely. Most people think the ECB will slash rates at its meeting next month, but Schnabel thinks “a rate cut in July does not seem warranted”. Policy is likely to loosen, but Europe still has its own inflation pressures, and we are not about to enter a full-blown easing cycle.

The UK is in a similar situation. Implied market expectations suggest the BoE will deliver a first cut in August, and these expectations are aiding what is currently a strong period for UK equities. This is encouraging, and hopefully it marks an end to years of underperformance for British stocks, even if European and US stock markets still have the upper hand for the period since the year started (appr.8% UK, 10% EU and 12% US). UK based investors should bear in mind that short term movements in the UK Large-Cap Index will not be exactly mirrored in portfolio values, which are based on globally diversified investments. That might seem like a bad thing when the UK Large-Cap Index does well, but the long-term picture clearly favours globally diversified portfolios.

Interestingly, UK stocks used to be considered a pretty adequate proxy for global stock performance – thanks to the UK Large-Cap Index being dominated by large multinationals. In recent years, though, the UK Large-Cap Index has become overwhelmingly focused on a limited number of sectors, like energy, consumer staples and banks. Again, that is good when those sectors do well, but it means the UK stock market is more disconnected now from UK and global growth trends and therefore no longer constitutes an adequate yardstick for equity returns in general.

Speaking of global growth, one of the most prominent stories last week was the US imposition of another bout of tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) and solar panels. Compared to the tariffs introduced under the Trump administration, this is likely to have only a small effect on the Chinese and US economies, given the much smaller volume of affected trade, but trade hostilities between the two are likely to continue as we head toward the US election. Trade war between the world’s two biggest economies has already knocked China from top spot on the list of US trading partners (which is now Mexico).

Encouragingly, EU policymakers are trying to stay out of the spat, even though the US move is likely to put even more Chinese downward price pressures on European manufacturers, given the overcapacities in EV’s and solar panels that state subsidies and lack of domestic demand have created in China. This is perhaps why Beijing is promising more support for its ailing domestic economy and consumers. This should be a positive for broader global, rather than just US growth, and given Europe’s larger export orientation, this would benefit Europe more than the US. However, the deterioration of US-China ties makes things difficult to project with confidence. In this environment, it is hard to get even more optimistic about the world economy and corporate earnings growth than what is already reflected in asset prices. Markets’ fairly middling week, with the US markets taking the lead again, probably reflects that. Investors will at least be pleased that, after the April setbacks, portfolio values are touching new all-time highs.

China building a new world order, but still living in this one

Vladimir Putin’s visit to China last week has brought the Russia-China relationship into sharp focus. Just after the Russian president invaded Ukraine in early 2022, he and President Xi toasted the two nations’ “no limits” friendship. It was a signal of things to come, as much as a rebuke of Western sanctions. Economic and political ties between the countries have grown dramatically since, with bilateral trade reaching $240 billion last year, which is very considerable given Russia’s economy comparatively small size these days (for comparison: China trade with US is $575bn and over $800bn with EU).

Business is booming, and the leaders apparently see eye-to-eye on matters of global politics. Ties have been growing for over a decade, but accelerated after Western sanctions forced Russia to find new trading partners. Not only is China one of Russia’s key lifelines, but some Russian businesses have found Chinese goods as cheaper alternatives to the European brands they used to use. In an interview with Xinhua news, Putin beamed: “Today, Russia-China relations have reached the highest level ever, and despite the difficult global situation continue to get stronger.”

One of the key things the presidents agree on is challenging US supremacy on the international stage and creating a multipolar world where nations’ internal politics are their own business. China has been building its economic ties with countries around the world for years, most famously through its belt and Belt and Road initiative of building infrastructure in countries deemed friendly. This new world order is now taking shape, with China claiming to be the largest trading partner of 120 countries.

China’s drive to create an alternative to the US-led liberal democratic international order has been going since the People’s Republic was established 75 years ago, but it has accelerated in recent years out of necessity. Former president Trump kickstarted the US’ trade war against China, and President Biden has not only continued the fight but opened up multiple new fronts.

Last Tuesday, the White House quadrupled existing tariffs on imports of Chinese electric vehicles, and last month signed a law that bans the TikTok app from US platforms unless it separates from Chinese parent company ByteDance within a year. These moves have severely dampened trade between the world’s two largest economies and, as of 2023, China is no longer the US’ biggest trading partner.

Relations are likely only to worsen for the foreseeable future. With the US election fast approaching, both candidates are trying to outdo each other’s toughness on China. The EU, historically much slower to react to Beijing’s perceived unfair trade practices, is considering tariffs or other measures as retaliation for the ‘dumping’ of electric vehicles and other goods, too. Chinese officials and businesses have accepted they need to prepare for colder relations with the West.

However, the fact China wants a new world order does not mean it has given up on the current one. On the contrary, Beijing is trying to contain the fallout from its trade war with the US through the very US- dominated institutions it wants to challenge. In March, China launched a case against the US at the World Trade Organization for its electric car and renewable energy tax credits.

Beijing is also still keen on attracting investment. The recent tax waiver on Hong Kong listed stocks was designed to boost investment from the mainland, but it is part of a suite of measures to boost China’s capital markets. This includes a policy directive last August to equalise treatment of foreign and domestic businesses, and increase tax support. Chinese stocks have rallied over the last month in response.

Much of this is out of necessity. China’s economic slowdown has prompted the government into various stimulus measures, including more issuance of long-dated central government bonds, and reportedly putting pressure on local governments to buy unsold property developments.

Interestingly, devaluing the currency to boost exports has not been one of the measures used. We wrote recently that the People’s Bank of China is allowing the renminbi to trade near the top of its target band against the US dollar – historically, a sign that devaluation is coming – but is still officially maintaining it. A desire to attract foreign investment could be one reason for this, as a weak or volatile currency could scare off investors.

It is difficult to know how much longer China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, can go on maintaining its defence against its weakening currency, the renminbi, but devaluation would almost certainly sour US relations even more. Ultimately, while Beijing wants to create a new world order, it is fully aware that it has to live in this one. That means we will probably continue to see policy signals from China that might look inconsistent – buddying with Russia while also trying to appease western investors and policymakers.

That makes China a curious proposition for Western investors. Despite some rhetoric to the contrary in previous years, Chinese assets are not ‘uninvestable’. In fact, the recent rally in Chinese stocks – coming as US stocks fell – shows that China can offer not just decent returns but valuable diversification. However, the geopolitics, not to mention erratic domestic politics, create unique risks. As with any investment, these risks must be understood and accounted for.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.