Published

1st July 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –1st July 2024

Last Friday marked the end of the second quarter and the day after the first, and for Biden disastrous, televised debate of the 2024 US Presidential election – yet markets have been reasonably calm. Large institutional investors are in the midst of their calendar driven portfolio rebalances without causing big price moves between asset classes.

Last Thursday’s US Presidential debate was always going to grab our attention, and we all knew that the event was a test of fitness for Presidency rather than a proper policy debate. Would Biden be sharp? Would Trump lose control?

As such, it probably could not have been worse for Biden. His loss of focus under pressure was enough for even staunch Democrat voters to doubt if they can vote for him, and losing even a small number of voters would make the contest unwinnable for Biden.

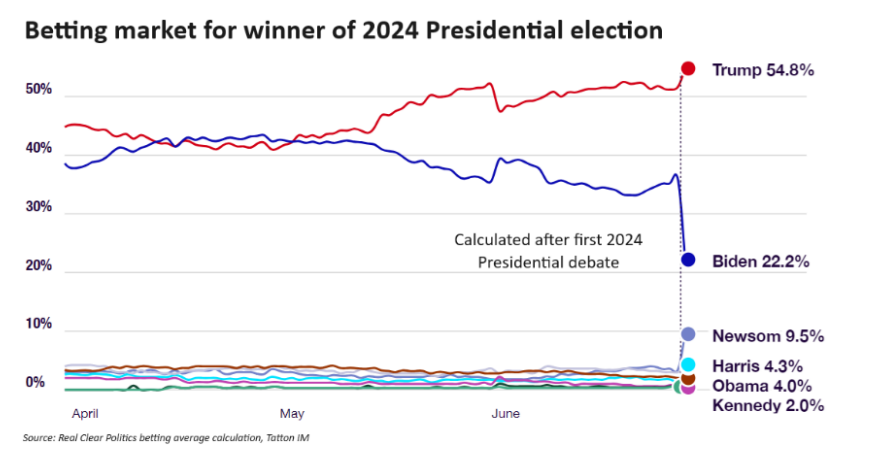

The betting markets are (we believe) the clearest and more honest way, compared to opinion polls, to see what people and markets are thinking. Real Clear Politics aggregates various bookmaker quotes to calculate the market view of who will be elected President in November, shown in the chart.

Trump’s odds improved by about 4% to 54.8%, but Biden slumped by over 15% to below 25%. Meanwhile (not shown here), the likelihood of a Republican victory is at 60% (according to Betfair Exchange Politics site).

Victory for the Democrats is now less likely if Biden stays as candidate. Biden has to overcome the ‘fit for office’ hurdle, that looks difficult currently, and it will look more and more difficult with each passing day. Meanwhile Trump does not have to do anything other than look presidential.

In the days since the debate, Governor of California Gavin Newsom has become the market’s clear alternative to Biden should the Democratic Party seek a different candidate. Of course, the question is will they? If the Democrats’ internal polls say they have as good or better chance with another candidate, then they would have to convince Biden.

We have noted before that markets appear to be rather blasé about the whole affair. As the debate ensued, US stock market futures rose somewhat while US treasury bond prices fell (meaning that yields rose). The dollar also rose. International stocks were a little weaker. This implies that investors are currently expecting a slight near-term benefit for US growth should Trump win, but that it may also mean a worse budget deficit.

However, we think that the many elections which are taking place have something in common, in that most people think that many important policies will not be clear until well after the elections are finished.

To some extent, this has always been the case, but the nature of politics does seem to have changed in recent years. Manifestos are more “aspiration” than policy detail. Perhaps this is inevitable given how complex modern society and government has become.

Here in the UK, a Labour administration looks a racing certainty after this Thursday’s election. Being ostensibly centrist, their manifesto is much less scary, but markets still cannot claim certainty on actual policy and finance, the things that matter most to investors. At least here, investors generally appear to believe that the policy mix will not create much downside. Still, politics will be a factor through the rest of the year in markets as aspirations transform into actual policy detail later.

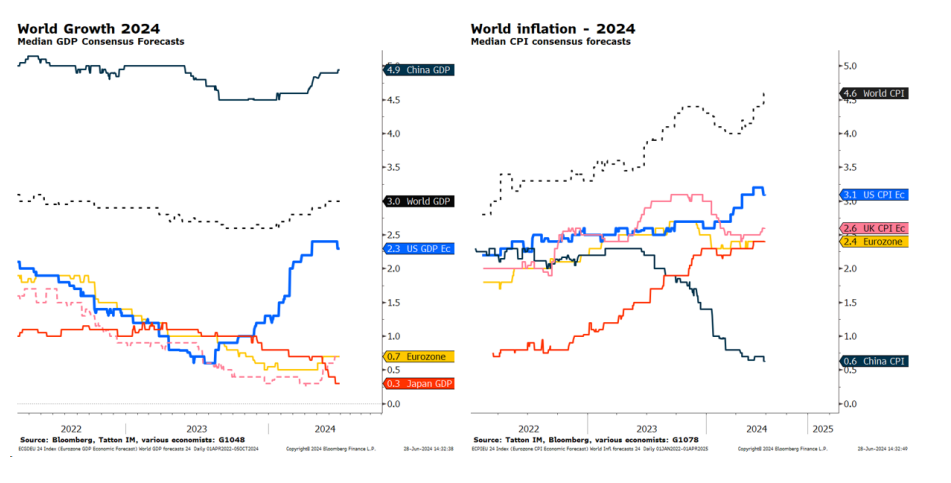

At the end of the first half of the year it is good practice to have a look at the wider economic picture and how it may have changed since the beginning of the year. Global economic data continues to be mixed with a slight positive bias, but economists have revised up world growth estimates for the full year. The charts show how Bloomberg aggregates of economists’ forecasts for real growth and inflation are evolving:

Some of that is because of China’s policy push to bolster economic activity (which will probably have little benefit for the rest of the world at the moment, except for driving down goods inflation). It’s notable that China’s inflation forecast keeps falling, which speaks of weak rather than strong demand. In the US, households have become more cautious in their spending and are reluctant to move house, causing a buildup of unoccupied new houses. Meanwhile US increases in corporate capital expenditure seems to have slackened somewhat which may explain some of the much discussed, extensive volatility in AI chip maker Nvidia’s share price during the week.

For Europe and the UK, growth expectations are lacklustre but have not slipped, in itself mildly encouraging. Inflation expectations have started to edge higher although not yet to worrying levels. Of course, the low level of growth means that the economy is vulnerable to shocks, and therefore politics and central bank policy may be even more important here than elsewhere.

A loss of growth momentum in the US is apparent both in economic surprises (data keeps undershooting economist expectations) and in last week’s slew of profit warnings from consumer-facing companies ahead of Q2 results. General Mills (makers of Cheerios), Walgreens Boots, and Nike stock prices fell sharply after both issued profit warnings and gave gloomy outlooks, and follows on from similarly downbeat announcements from the likes of McDonalds. Consumer brands are saying that their customers are seeking cheaper alternatives.

This is bad news for those companies, but we can spin out a positive economic story as well. US households have been saying that they fear inflation is on the rise again, but their behaviour says they won’t let the brand leaders get away with the latest price rises. Jobs remain in strong supply even if wages are no longer rising sharply so a fall in inflation will keep real disposable income on the rise.

A turn down in inflation driven by discerning consumers and other favourable factors will allow the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates, while borrowing rates will also probably decline (as long as politics doesn’t increase fears over budget deficits getting out of control). Underlying demand for housing remains strong (because jobs remain plentiful) and a fall in mortgage rates is likely to reverse the softness in housing construction. Gentle economic slowing should therefore lead back to more growth amid an otherwise stable dynamic characterised by tight labour supply driving business investment into productivity enhancing technology advancements. Europe is in a similar position although admittedly with softer underlying growth.

Thus, as we head into the year’s second half, companies broadly remain on a positive path. The risks will continue to emanate from policy volatility. In that respect, we’ll know a bit more later this week after the UK elections and possibly a lot more after the second round of the French election.