Published

19th August 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

Tornado rather than hurricane

After stocks sank in early August, we warned that volatility could ripple on, and the market storm turn into a full-blown hurricane. But last week saw a remarkable dying-down of the volatility, like a whirlwind that passes in an hour: stock markets climbed up all over the world, with no hint of pullback. The rally has been so strong that global stocks are almost exactly where they were at the end of July – before the sharp selloff. Fears that sparked the midsummer sell-off seem to have faded too, helped by stronger-than-expected US economic data.

Market positivity is of course good to see – and we said all along there was enough to be positive about – but the rapid and sustained turnaround is a little eerie. Our medium-term outlook is still pretty bright, but we think further market mood swings remain likely.

Economy proving the doubters wrong?

The turnaround was undoubtedly helped by some good economic data last week. Here in the UK, GDP grew 0.6% in the three months to June, in line with economist expectations and marking the second consecutive quarter of expansion. It means year-on-year growth in Q2 was the strongest it has been since late 2022, a sign that Britain is finally recovering from its recent difficulties.

Fears about the US economy have faded too. Stocks were buoyed by last Thursday’s retail sales report, which showed a month-on-month increase of over 1% in July. This was accompanied by a range of positive consumption signals: lower long-term yields are leading to more mortgage refinancing (indicating confidence about borrowing to spend) and automobile demand is picking up from weak levels. All of these suggest that the American consumer is still proving the doubters wrong.

Recession fears in recent weeks had been focused on unemployment and how it might spiral. The ‘Sahm Rule’ recession indicator that was triggered a few weeks ago, for example, is based on the idea that, when job losses start rapidly increasing, that feeds into weaker demand, weaker sales and hence further job losses. The thought that we might be on that precipice was one of the reasons markets were so jittery.

But if the unemployment spiral was happening, we would see it feeding through into weaker consumption. Consumption would be among the weakest of US economic indicators – but actually it looks like the strongest. The US economy is undoubtedly slowing, but consumers are yet again the force to keep it going. That should only improve when interest rates come down. If the US does pull off a ‘soft landing’ (growth slows enough for rates to come down, without going into outright contraction) we can thank American consumers’ resilience.

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

We have every reason to think a soft landing is on the cards. As we noted the previous week, for example, corporate credit has been very stable, compared to the turmoil in equities. That suggests investors are still very willing to lend to companies – the opposite of what you would see if a recession-induced bankruptcy wave was about to hit. But we should not confuse this soft landing with a ‘no landing’ scenario (growth comes back strong without any material slowdown).

US nominal retail sales were up 1% month-on-month in July, but it was growing from a fairly low base in June. Looking back over six months, retail sales have in aggregate been fairly sluggish. Yet, markets reacted like it was fantastic news. We mentioned the dampened oscillation that tends to follow large market corrections (like a pendulum swinging to a stop) the previous week, but last week there seems to have been no oscillation at all.

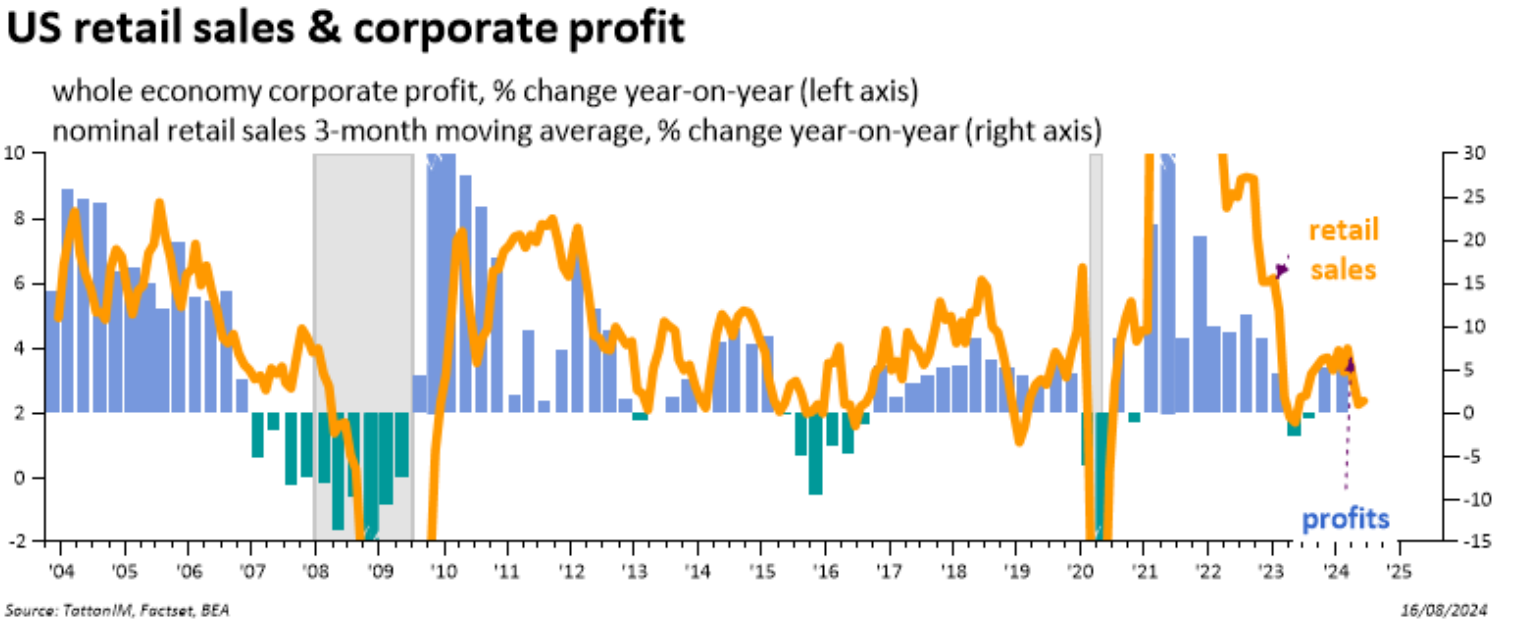

Retail sales and corporate profits tend to change together, as we would intuitively expect. The chart below shows their relative behaviour. The retail sales data is slightly more timely than the whole economy profits data, and it indicates that next quarter’s profit growth is unlikely to be stellar.

Did markets overreact to negative signals before and are course-correcting, or are they overreacting to positive signals now? The answer is probably somewhere in the middle, but it is hard to say for sure yet. The direction of last week’s economic and financial signals was positive and did not add to the previous week’s negative outlook. However, data points can be noisy (particularly short-term data like month-onmonth retail sales) and there will inevitably be some releases that look a little worse. The worry is that markets could hyperfocus on those too, bringing another bout of volatility.

We will get a clearer picture after the Jackson Hole conference for central bankers, where Fed chair Powell is set to speak. Markets’ rate expectations moved down sharply after the unemployment numbers, suggesting a 0.5 percentage point cut from the Fed in September and more to follow. Improved signs since then suggest that 0.5 might not be needed, but we will have to wait and see.

Signals from around the world.

The ‘Magnificent Seven’ US tech giants have lost some of their magnificence in recent weeks, and Google’s legal troubles are probably not helping. A US judge ruled in the previous week that the company had illegally monopolised the search engine market but left the punishment for a separate ruling. Last week, the Department of Justice was reportedly considering a breakup of the company. Needless to say, that would be hugely negative for parent company Alphabet and the entire ‘Magnificent Seven’ – a sign that their market power might be challenged by regulators.

What happens will inevitably depend on who wins the presidential election, as we write about in a separate article. One suspects that a Harris administration would take a harder line than Trump. However, at one level, there is bipartisan commonality in Washington in their dislike of the mega-cap tech firms – but both sides accuse each other of being on the tech firms’ payroll.

Another rare point of agreement is fiscal laxity – to the detriment of the US fiscal outlook. We argue below that Harris might actually be better for fiscal discipline than Trump. Her improved odds recently might therefore be a positive for bond prices.

We also write about the positive long-term case for Japan below. With some positive data signs last week (following the previous week’s meltdown) there has been talk that the Bank of Japan might be able to continue raising rates after all – possibly in December. This would likely strengthen the yen further, and interestingly the biggest beneficiary could be China. China has kept its own currency stronger than the yen this year (by maintaining a dollar-peg) but that has forced its central bank into tight policy. A stronger yen might allow the bank to loosen its grip, giving the world’s second-largest economy much-needed support.

Would ‘Kamalanomics’ mean us fiscal expansion?

With just over 80 days until the US presidential election, Vice-President Kamala Harris has become the favourite to win. The gap between her chances and those of former president Donald Trump is very slight (the odds are close enough to be a toss-up) but consistent across all the major indicators: she leads in the polls, in betting and prediction markets, and the most renowned election forecasts.

Harris has now begun to roll out more detailed policy snippets. Last Thursday, she announced plans to extend tax credit for families, with babies under a year entitling the family to a $6,000 credit. Other tax giveaways were proposed, focused on children. Harris has engineered quite a turnaround. A month ago, forecasting doyen Nate Silver gave the democratic presidential candidate a 27% chance of winning the electoral college in his official model, and suggested that was overly generous. But since “the democratic presidential candidate” stopped being Joe Biden, the party’s chances have shot up to 56%.

A month ago, markets were operating under the assumption of a second Trump presidency from 2025. We wrote about his expected economic agenda and its effect on assets in response (good for small and mid-cap stocks in the short-term but increasing bond market risks over the long-term). But we now have to think about what a Harris presidency might mean for the economy – and how markets might react to this very close election.

The first thing to point out is that, with neither candidate a clear favourite, the odds of a ‘clean sweep’ for either major party – winning control of the House, Senate and presidency – are low. The Republicans are favourites to gain control of the Senate, thanks to a slightly more favourable batch of races (elections to the Senate are staggered, with a third of seats up for grab every two years). The Democrats, meanwhile, are slight favourites to take control of the House of Representatives from their opponents.

Without control of both houses of congress, presidents typically struggle to implement their agendas fully, and policies often have to be watered down to pass through the legislature. The gridlock has become worse in the last 15 years too, thanks to increased polarisation between the parties. That means fewer big changes, and hence fewer opportunities for politics to upset (or cheer on) markets.

The Vice-President still remains coy on what ‘Kamalanomics’ might mean for the bigger issues. Most people assume her economic policy would be a continuation of Biden’s, but the majority of voters disapprove of the current administration’s handling of the economy (despite most objective metrics looking very strong). If Harris were to enact such economic policies – either through an unlikely Democrat clean sweep or some executive-order workaround – it is far from clear how markets would react.

Harris’ late call-up means she can distance herself from the unpopular parts of Biden’s legacy. This will probably mean talk of lowering inflation – since historically high inflation in recent years is high up on most Americans’ list of concerns (the psychological impact of prolonged inflation is seen as one of the reasons why Americans are more downbeat about the economy than spending and employment figures would suggest). There were reports this week, for example, that the Harris campaign will emphasise the cost of living – rather than Biden’s usual talking points of job creation and made-in-America manufacturing.

If Harris sticks to the inflation-lowering agenda, it is possible that her administration would be more fiscally disciplined than either Biden or Trump. As we have written before, US government debt metrics (deficit spending and debt-to-GDP) have deteriorated under successive administrations, and Trump would almost certainly stretch the deficit further via tax cuts.

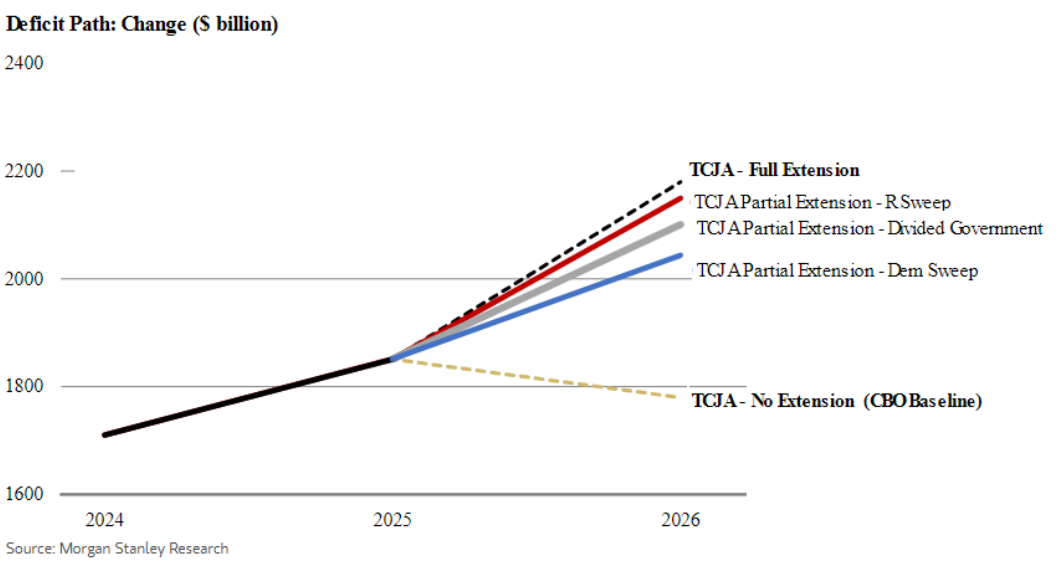

Above is a chart from Morgan Stanley Research which identifies the projected paths for the deficit, in considering how both parties will deal with the biggest fiscal decision of a new administration: the aftermath of Trump’s 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).

The wide-ranging act had a large number of tax-affecting measures (mostly cutting tax), some of which are time limited to only seven years. This made the bill acceptable to the more fiscally conservative Republicans, but everybody knew that the 2025-26 expiration would feel like a tax rise. Thus, both parties now favour making some or all tax cuts permanent (even though Kamala Harris favoured an outright repeal of the TCJA when campaigning for the Presidential nomination in 2020).

Both parties are in favour of some fiscal expansion, but Trump’s likely path is more immediately expansionary. As Harris’ policy becomes clearer, it may be that Trump will be tempted to be even more expansionary in order to re-energise his campaign.

Modern-day America has not had debt-inspired bond market sell-offs of the Liz Truss ‘Mini’ Budget kind. That is thanks to its “exorbitant privilege”: owning the world’s deepest and broadest asset market and controlling the global reserve currency. But this invulnerability gets harder to maintain as debt becomes less sustainable. The situation is made worse if the US pursues trade protectionism – as it would put pressure on capital inflows.

Protectionism is a cornerstone of Trump’s agenda: he raised tariffs against major trading partners in his first term and has promised to raise them much higher in his second. Some thought that Biden would reverse those policies, but the president has continued or even expanded them.

If Harris wanted to separate her policies from Biden while sticking to the ‘Trump is bad for your wallet’ message, preaching fiscal restraint and fewer tariffs would be a clear way to do it. Markets would probably like that message, although there would be more than a few voices expressing nervousness about growth if it meant higher taxes or an end to tax exemptions (as in the upcoming expiration of Trump-era corporate tax measures).

After substantial tax cuts under Trump, and trillions invested under Biden, many external observers warn that there is no capacity in US finances for another big fiscal expansion. Still, it is unlikely that this will stop Trump from trying. It may not stop Harris either, although we suspect the latter candidate would be less willing or able to run the risk of a ‘Liz Truss moment’.

Each party may still be tempted to offer “giveaways” to voters should their campaign falter in the final stages, given that the American public shows little immediate concern over the federal debt load. Rather, just as it was here in the UK, it could be bond markets that express disquiet by sending yields sharply higher. Perhaps we should take comfort that the UK moment was short-lived. Such an episode would in that case offer a good buying opportunity.

The long-term case for Japan

Drama is not something Japanese markets are that used to – or, clearly, that fond of – but the nation’s currency and stock exchanges were at the centre of a global surge in volatility over the last few weeks. The TOPIX, Japan’s benchmark equity index, lost over 20% from the open on 1 August to the lowest point on 5 August. It has regained almost all since, now down less than 2% at the time of writing.

The yen, having been the weakest major currency in the first half of 2024, went from more than ¥160 against the dollar in July to ¥144 the previous week (one dollar will get you ¥147 at the time of writing). These swings were part of an unwinding ‘carry trade’ (borrowing cheaply in Japan and investing in higher-returning regions like the US) that shook global markets. But we noted that the market shakeout might not be all bad for Japan itself. The long-term investment case for Japan remains.

Profitability has improved structurally.

One of the biggest long-term gripes international investors have had with Japan is poor capital efficiency. This has been a consistent theme through decades of low growth and stock market stagnation: Japanese companies are just not very good at generating profit. Antiquated corporate structures, aversion to foreign ownership and extreme risk-aversion at the board level have been suggested as causes of this inefficiency.

Japan has been striving to reform those corporate structures for over a decade. These efforts have started to bear fruit in recent years: firms have become less averse to large foreign share ownership, and shareholders are more willing to vote against company directors. These changes have been part of investors’ positivity on Japan this year – a rally that broke the TOPIX all-time high record, which had stood since 1989.

This is not a case of Japanese companies suddenly allocating their money perfectly. Capital efficiency metrics are still significantly below Europe and (especially) the US. But improvement, even from a low base, should mean greater profitability. The shakeout of speculative market positions in recent weeks could also help align shareholder incentives toward long-term profitability.

Exports will remain competitive.

In terms of international trade, Japanese goods and services are currently very competitive. The yen’s longterm slide against the dollar (it was barely above ¥100 at the start of 2021), along with Japan’s lower inflation, means that Japanese labour costs are well below the US, in dollar terms.

Japanese workers are among the most highly skilled and educated in the world, so the discount to American workers represents significant value for Japanese firms. Exporters are capitalising on that to make themselves competitive. And the signs are that this is working. Honda’s earnings from Q2, for example, showed healthy growth during a tough period for carmakers globally.

Even with the yen’s recent strength, it is still very weak in historical and purchasing power parity terms. Goldman Sachs point out that companies’ future profit guidance reports are mostly based on an assumption of ¥140 to the dollar – and we were arguing that Japanese labour was cheap back at ¥120. The Bank of Japan’s structural dovishness – with the governor dialling back talk of further rate hikes once markets threw a tantrum – will ensure that the yen will stay below those levels.

But what about growth?

Japanese economic growth indicators have been disappointing this year, but the hope has long been that strong exports will lead to higher wages, and eventually self-sustaining domestic demand. Japan has been notoriously bad at making that last step but last week’s data for April-June 2024 GDP has suggested that the comprehensive picture has been better than individual indicators.

Morgan Stanley Research commented thus:

“Real compensation for employees shown positive YoY growth: Among demand categories, personal consumption rose 1.0% QoQ, the first upturn in five quarters… Wage growth spurred a recovery in incomes. Real compensation for employees grew 0.8% YoY, the first positive figure since 3Q 2021. Though related data are not available at the preliminary stage, we think that disposable incomes were helped by income tax breaks in June”.

Goldman Sachs researchers found that recent earnings strength was driven by high-quality domestic demand.

Many investors will be sceptical about the sustainability of Japan’s growth, given its track record. There are two important points to say to the sceptic, though: firstly, exporters (which now represent a larger proportion of the Japanese economy than ever before) will still get a profit boost if domestic demand is weak and, secondly, growth pessimism is why Japan’s equity valuations are so low. Valuations, in terms of price-to-earnings ratios, are well below those in the US and Europe. To stay that cheap, one would have to assume that growth will be as weak as it has been recently.

We have little reason to be that pessimistic. Even with Japan’s historic sluggishness, we should expect export strength to improve domestic demand somewhat, and that should be enough to improve broad profitability, given the reforms mentioned above. This does not mean that Japan is suddenly seeing a ‘new dawn’ or an end to its long-term malaise. But it should improve the outlook for corporate earnings growth. Since stock values are based on those earnings, and Japan is still cheap in terms of currency and valuations, the longterm case for Japan still looks solid.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.