Published

18th September 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 18th September 2023

Central bank hawks determined to defang inflation

The European Central Bank (ECB) raised rates last Thursday, with the majority of its Governing Council members concerned that the inflation parasite may be alive for a while longer. Of course, parasites can continue to be robust while their host deteriorates. We discuss some aspects of the run up to this decision in a separate article below.

Markets took the somewhat unexpected news in their stride, with only the yields on short-dated money market paper increasing. The dovish tone adopted by ECB President Christine Lagarde, reinforced investor sentiment that this period of rate stability would last for a few months, before rates come down again after next spring. Indeed, euro-denominated bond yields fell with increased pessimism about the domestic economy.

We await the Bank of England’s (BoE) rate decision this week, but the ECB’s deliberations give us a clue to their thinking. Catherine Mann, one of the external members of its Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), has already signalled her vote for another rate rise. Other committee members seem more reluctant.

The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) released its August survey, wherein estate agent sentiment has become notably darker following some mid-summer lightness. They see little house-selling activity and expect prices to go lower in the coming months. This echoed the previous week’s Nationwide House Price Index for August, which showed a drop of 0.8% from July.

Often, a weaker housing market feeds into the wider economy and lowers inflationary pressures. We are not really seeing this at the moment. Transaction volumes have been low, and landlords are opting to pass on higher costs (interest rates and possibly energy and maintenance) to their tenants, rather than simply making greater margin.

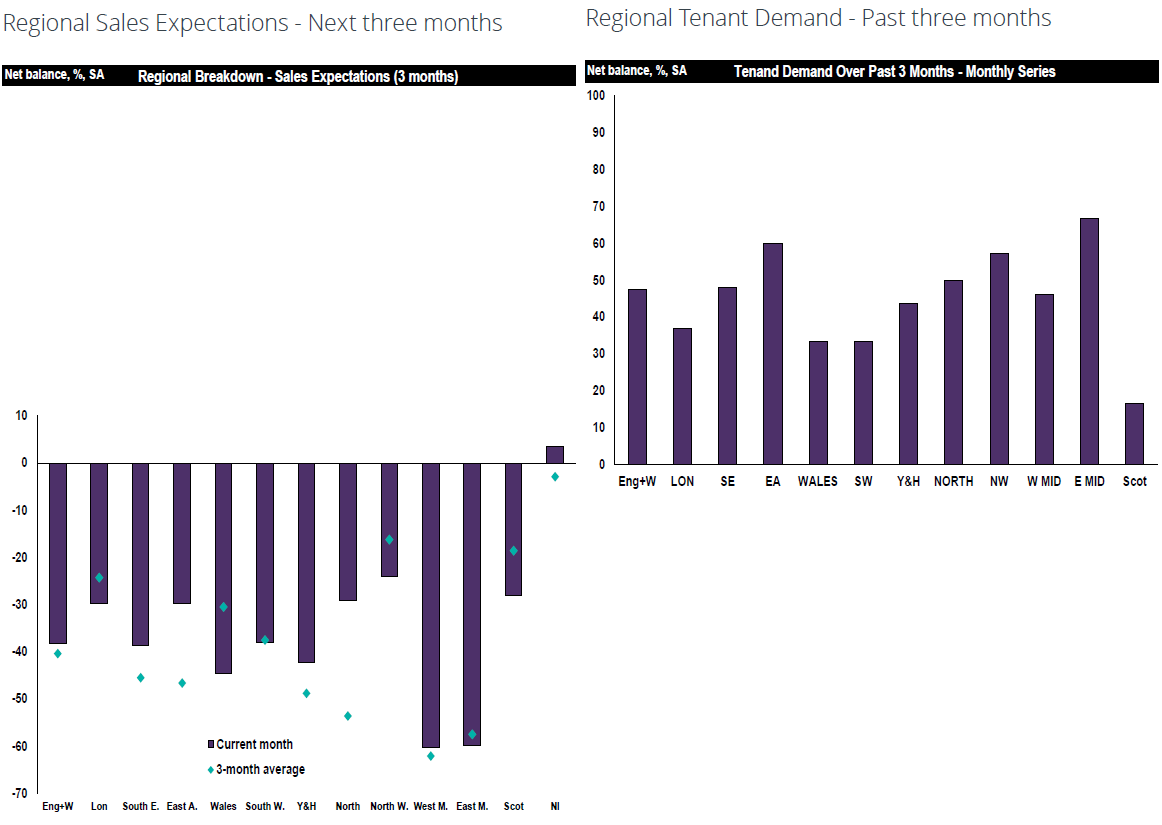

So, despite continued sharp rent rises, the after-cost yields are not higher than the new interest costs. We’ve put two charts together from the RICS survey that show the stark difference between the two parts of the housing market:

Housing markets are becoming a greater issue across the world, but the UK’s situation feels oddly similar to the recent problems in China. Xi Jinping chose to deal with the problem of affordability which has had a substantial impact on the domestic economy. Our government has to grapple with the impact on affordability of long-term housing undersupply for both buyers and renters. Elevated tenant demand allows landlords to keep rents high or increase them – and that is occurring during this period of change.

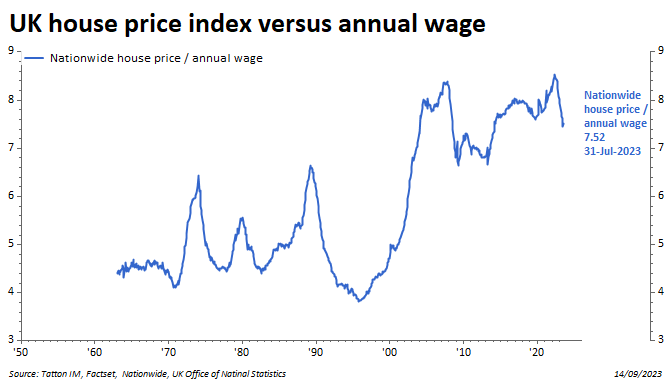

Meanwhile, the average cost of a house is now about 7.5 times the average annual wage (our calculation from the Nationwide data and Office for National Statistics data), down from 8.5 one year ago. It still has a long way to go before we get close to the pre-2000 level of below 5 times. Either wages will have to keep rising at a reasonable clip for a long time (which comes with inflationary tendencies) or house prices have to fall further, or both.

Across the pond, US retail sales and inflation showed more strength than expected. Generally, US actual activity data has exceeded expectations for a few weeks as opposed to sentiment data which has been more mixed. And China’s credit growth data has shown a glimmer of light, as did retail sales and industrial production, perhaps the sign of another economic bounce after the myriad of policy announcements.

As we head towards the end of the third quarter, US earnings expectations for next year continue to push higher, which is leading to a relatively broad sense of optimism. Stocks with good earnings expectations momentum are leading the performers rather than ‘thematic’ stocks like those associated with artificial intelligence. In general, institutional investors feel a lot more comfortable when earnings are the thing that causes equity price rises.

Overall, it’s noticeable across the board that volatility and associated risk has continued to edge lower, perhaps signalling a period of steady calm. The strength of the Arm Holdings NASDAQ debut (which climbed 25% after the IPO priced it at $51 per share) has helped as well. The positivity seems enough to offset another week of oil price rises.

Europe and the UK face some stiff headwinds compared to the Americas and Asia at the moment, and that is feeding through, particularly into the currencies. Both Sterling and the Euro have slid another notch against the US$ and, reversing the trend of the previous weeks, are now weakening relative to the Renminbi and stable against the Japanese Yen. Without the prospect of near-term fiscal or monetary policy action, this may continue for some time.

Interest rates in Europe: is the peak actually in sight?

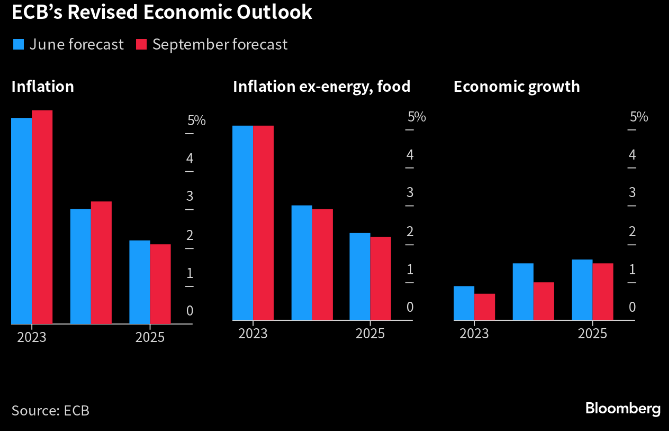

Only recently, it seemed as if ECB policymakers would hold off on another hike, following some dire economic data. Bank governors were reportedly split on how the continent’s undeniable slowdown might feed through into wage and inflation pressures, as well as the lagged effects of previous hikes. But news of a stickier inflation outlook rightly swung the market pendulum back to tightening expectations. In the end, the ECB raised its deposit rate once again by 0.25% to 4%. Given the frail economic outlook, and indications that rates may have reached a plateau, bond markets rallied and the euro sold off.

The ECB is in an unenviable position. The long-held consensus is that it was behind the curve in fighting inflation as the world emerged from the pandemic and, to rectify this and restore confidence in monetary policy itself, it should keep a tightening bias until inflation was unmistakably defeated. But unlike the US, inflation pressures in the Eurozone do not seem to be coming from economic resilience, but structural supply-side weaknesses the central bank has little control over. Furthermore, in Europe, as in any other economy, the full impact of monetary tightening hasn’t fed through yet.

European data worsened markedly over the summer, with business sentiment surveys painting a dour picture. The manufacturing slump spread into services, with both sectors now pointing towards contraction. It also looks quite clear that rate hikes have already had an effect on constraining credit. The European Commission subsequently lowered its Eurozone growth forecast to 0.8% this year, down from 1.1%. With inflation currently above 5% and expected to stay above 3% next year, that will mean quite a sharp contraction in real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

A huge part of Europe’s weakness comes from Germany. The continent’s largest economy and historical growth machine is experiencing not just a slowdown in growth, but an outright contraction. Its manufacturing sector – in particular its large automotive industry – is in decline, and expectations are still overwhelmingly negative. In an interesting role reversal from previous European downturns, France is making up for this economic weakness at the headline Eurozone level. Europe’s second-largest economy has avoided recession so far, but saw similarly downbeat sentiment surveys last month.

Weak growth is often a headwind for government finances, as receipts suffer and outlays grow. The German finance minister had previously warned that it would likely run a fiscal deficit of more than 4% of GDP this year, but reports last week suggest the figure will likely only be 2.5%. This creates some fiscal headroom for Berlin, which could be vital for embattled Chancellor Olaf Scholtz.

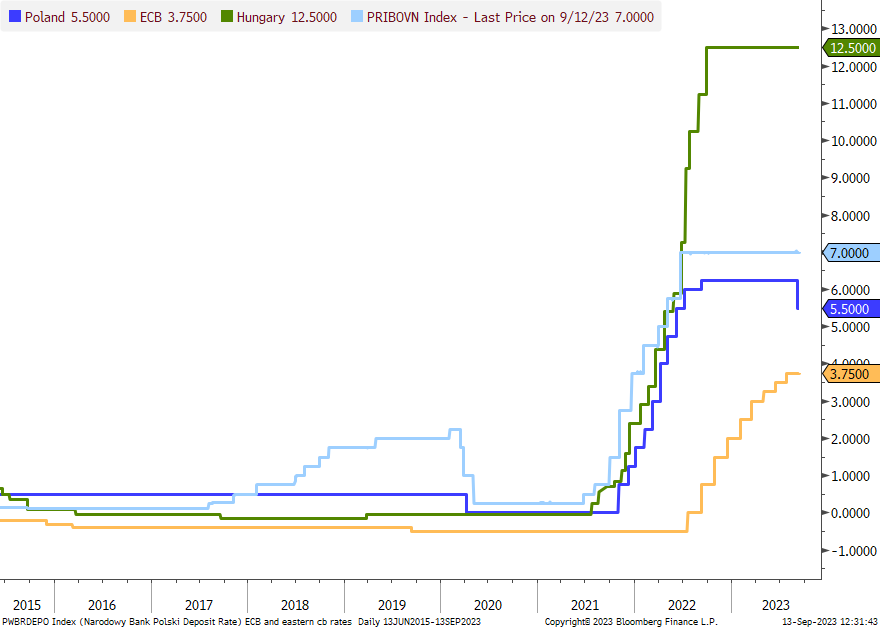

Looking ahead, there are certainly reasons to think Europe’s rate hiking cycle has peaked. Recently, Poland’s central bank surprised economists by announcing a 0.75% cut to interest rates, despite inflation still running in the double digits. Most commentators stressed the political motives behind this move: Poland has an election coming next month, and its central bank head is an ally of the far-right Law and Justice party fighting for re-election. This is no doubt part of the story. But at the same time, both Polish growth and inflation have fallen sharply this year and, given that the nation’s acute price pressures were largely Russian energy withdrawal symptoms, a policy reversal is not so outlandish.

In fact, inflation in the European Union’s peripheral nations – particularly eastern countries outside the eurozone – has come down sharply throughout the year, albeit still remaining high in most cases. This is despite many of the national central banks leaving interest rates untouched throughout 2023. As the chart below shows, countries like Poland and Hungary were quick to raise rates as they emerged from the pandemic and prices began soaring. This process was supercharged by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequently soaring energy prices (which eastern European nations are painfully sensitive to) but has long since cooled off.

We have written before about the ECB’s predicament that labour market tightness in peripheral nations was a big concern. Historically poorer countries, particularly those of the former eastern bloc, have acted as a source of cheap labour for a long time, helping to keep wage inflation low. This changed as wages started equalising between nations – such that wages in the east no longer act as such strong a counterweight to those in the north and west. However, the fact central bankers feel they can hold rates steady for so long – and in some cases, reverse course – suggests that those wage pressures are much less pronounced.

Much like emerging market central banks in South America, peripheral European policymakers were early to raise rates because they had to be, but now have more breathing space. The ECB is still deeply concerned about sticky inflation, but the direction of travel is clear. In particular, the fact that inflation has continued to fall in the places where labour markets might seem most susceptible to it is a good sign. That this has happened while interest rates have been held steady is even more promising. ECB governors will continue to worry, but the external signs are good.

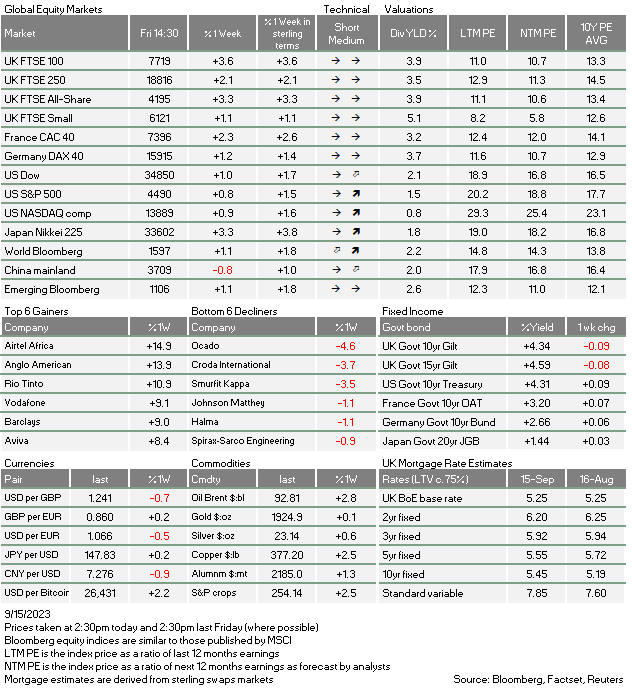

* The % 1 week relates to the weekly index closing, rather than our Friday p.m. snapshot values

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.