Published

18th November 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –18th November 2024

Reading Trump’s tea leaves

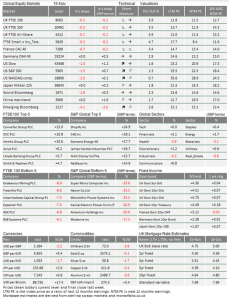

It was an up and down week for global stocks. Markets initially showed confidence in Donald Trump’s tax cut and deregulation agenda – but pulled back when Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell suggested interest rate cuts might have to be gradual. The S&P 500 was flat for most of last week but tumbled on Friday afternoon amid rising bond yields. This came against a backdrop of strong gains the previous week, a sharply higher dollar and weak equity markets in most other regions.

Markets are still generally bullish on Trump’s second term. This is easy to understand, but relies on a fair amount of guesswork. We still do not really know how Trump’s second term will impact the US and global economies, yet markets are betting on America First. That could be a recipe for some disappointment in the near-term, even if the underlying outlook is positive.

Will Powell disrupt the Trump trade?

The Republican party’s victory in the House of Representatives, along with Trump’s loyalist cabinet picks, mean the president-elect should have no trouble implementing his agenda. The promise of tax cuts and deregulation lit a flame under US stocks, and real (inflation-adjusted) bond yields kept climbing higher last week, suggesting that economic growth is expected to be stronger under Trump.

Positivity was initially helped by expectations that the Fed would press ahead with cutting interest rates, but chairman Powell tempered those expectations last Thursday. According to Powell, the US economy is “remarkably good”, and the Fed does not need to be “in a hurry” to cut rates. Looking purely at the data, that is quite clearly true, but ahead of a politically volatile second Trump term (in which Powell’s job is up for renewal) it feels like a bold statement. In the short-term, it reminds markets that expansionary fiscal policies can lead to tighter monetary conditions.

Over the longer-term, it sets up a fight over Fed independence between Trump and Powell alongside the Open Markets Committee. US yields hit 4.5% last Friday afternoon, and the increase is starting to hurt stocks. Trump backers are already blaming Powell, and an unwelcome tussle between the two now looks inevitable.

Also on Trump’s policy docket are tariffs and deportations, which markets conventionally dislike as they are bad for growth. But the reaction so far suggests that investors think Trump tariffs will mainly be bad for everywhere outside of the US. In the early part of last week, stocks edged down in the UK and Europe, and fell sharply in Japan and China. So, rather than hurting US economic prospects, tariff expectations are reinforcing investors’ belief in US economic exceptionalism.

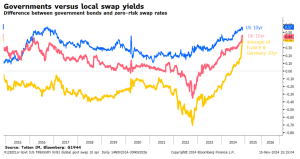

Bond risk for some, bond rewards for others

The move up in US bond yields was partly about higher expected growth and partly about the Fed – but we have argued for a while that bonds are also reacting to an expected deterioration of the government’s debt position. The best way to see this is in the difference between long-term government yields and the rate offered in bank swap contracts of equivalent maturity. The latter are effectively guaranteed by the central bank, so are therefore a truer ‘risk free’ rate than government debt. The spread of yields over swap rates keeps widening, which suggests that markets see US treasury debt as genuinely riskier than before, as the chart below shows.

The interesting thing last week was that this measure of government debt risk also increased in Europe. This could be down to political instability in Germany and France, but we suspect the main reason is that markets expect Trump’s policies to have the knock-on effect of forcing European governments to spend more. The most obvious way this would happen is through increased defence spending – should Trump make good on his promise to dial back America’s payments into NATO. European leaders might also have to invest more in their economies, once US tariffs bite.

UK bonds, meanwhile, have come down in the last couple of weeks. In Rachel Reeves’ speech at Mansion House, the Chancellor talked up the need to improve UK private investment and recognised the importance of financial services for the UK economy. Markets took it well, particularly the message that pension funds might be encouraged to invest money in private companies rather than just government bonds – boosting private sector growth.

Some worry this might destroy demand for UK bonds and push up yields, but the trade-off is always about how well growth (and hence tax receipts) is supported. The fact bond yields fell slightly last Friday shows that the trade-off is working. We previously noted that UK bond yields had a consistent premium over US yields and were being driven by the latter – but the difference between the two narrowed last week, in a sign that things are expected to be calmer here.

Are markets too pro Trump?

We worry that different parts of the Trump trade narrative do not really fit together. Growth and inflation are expected to be strong, for example, but markets are pricing a comparatively small change in interest rate expectations. Investors also think non-US regions will suffer from Trump’s tariffs, but are not expecting other governments to retaliate with tariffs of their own, or else do not think that such retaliations could hurt US growth.

This could be wishful thinking, particularly with regards to China. Beijing is currently stimulating its domestic demand after a prolonged economic malaise, and is expected to beef up economic policy in response to Trump’s threatened 60% tariffs. The impression from most onlookers is that Trump caught China off guard in 2016, but in 2024 they are prepared. Beijing’s approach to the first Trump trade war was often about appeasing the US president, but there is a good chance that China will be more aggressive this time around. Chinese officials could impose significant tariffs of their own, or withhold certain key exports like cobalt (for which China dominates global production).

This is not to say that we do not believe the pro-US story. We just think Trump’s long-term effect on markets is more uncertain than investors currently seem to appreciate. How US companies fare during this period – and their expectations for the near future – will be important to watch. This week, AI chipmaking giant Nvidia will give a quarterly earnings update, which has become an important day in the market calendar. It is even more important in the current context. We will wait for further signs.

Is Europe investable?

Europe is in a very tough spot. The economy has been squeezed on one side by surging energy prices, and on the other by Chinese overproduction and waning reciprocal demand. Partly because of those troubles, the continent’s two largest economies look politically unstable. To make matters worse, newly elected Donald Trump is likely to slap tariffs on European exports to the US. That is why Europe has been the worst performing equity region in recent weeks, and why the euro has sunk in value through the autumn. There is no denying the difficult position European assets are in, but might investors be too pessimistic?

Germany’s struggles are Europe’s struggles

Germany and France dominate investors’ outlook on Europe, and their current problems are symptomatic of the EU’s more broadly. Macron’s electoral defeat in the summer and the collapse of the German government recently were seen as extremely bearish for the euro, which has lost nearly 3% of its value against the dollar over the past week. Just as in France, the German government unravelled because of disagreements over spending and fiscal rules.

A federal election will now be held on 23rd February, in which – according to polls – Chancellor Scholz’s SPD will likely lose to Friedrich Merz and the CDU. Markets would be comfortable with that switch – but the risk is that the far-right AfD gains enough support to play a role in government.

Germany’s fraught politics are largely the result of a hit to real living standards. Its manufacturing- and export-dependent economy is squeezed on both the cost and revenue sides. Weening off Russian gas has left German (and broader European) energy prices around four times as high as the US. Meanwhile, producers are struggling with a global manufacturing recession that was made in China. Sales are already suffering from Chinese overproduction – and the possibility of Trump tariffs compounds the problem.

It is telling that the government fell apart over government debt and fiscal rules pertaining to public infrastructure investment – always a contentious topic in Germany. This shows it is not only the Eurozone’s economic fundamentals that are weak; its institutional strength to address those problems is hampered too. This is also true in France, where the divided parliament rejected a budget bill last week, making France’s fiscal future uncertain.

Investors still can’t find a reason to buy cheap European stocks

Donald Trump wants to put tariffs on European goods, so markets interpreted his election as a hammer blow to European risk assets. The euro’s decline went hand in hand with a sharp move down in expectations for medium-term Eurozone interest rates – despite US rate expectations moving the other way. Basically, investors think European growth is so weak that the European Central Bank (ECB) will be forced into significant monetary support.

That makes last week’s fall in European equities look even worse since, all else being equal, a dovish ECB should be positive for growth and asset values. Markets are not currently seeing any upside from the ECB’s sharper expected rate cuts. Instead, they see the adjustment as a pure growth downgrade, judging by the fact that bond yields have come down at the same time. The latter suggests that a weaker euro is not expected to be inflationary.

Markets lack confidence in European growth and, unfortunately, businesses and consumers seem to share that view, based on sentiment surveys. European stocks are valued (in terms of price to earnings ratios) much lower than in the US, especially when accounting for the difference in interest rates. That relative cheapness should encourage investors looking to pick up a bargain, but that can only lead to sustained upside for European equities if there is some reason to be positive about underlying growth.

Markets are ignoring Europe’s upside

Thankfully, there are some reasons to be hopeful. Both of the price squeezes on Germany – and by extension, Europe – could improve. The Chinese government is getting serious about its domestic demand problem, and if its stimulus significantly boosts consumption, European exporters should benefit. Meanwhile, Trump’s election makes it likely that Ukraine will have to cede territory to Russia in exchange for an end to the conflict. Whatever you think of that outcome, it might result in less pressure on energy prices.

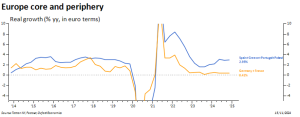

Moreover, for all the gloom, there are large parts of the European economy which are doing quite well. The combined GDP of Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain is equal to Germany, and this southern region is growing at a decent pace (although Italy is perhaps more like France and Germany).

This is the reverse of what we saw in the decade before the pandemic, when Germany powered ahead and the southern ‘periphery’ faltered. Not only is southern Europe improving, but it is doing so as interest rates

are coming down and – because of improvements in the underlying economies – while government bond yields are much closer to Germany’s than in previous eras.

That is a strong recipe for southern European growth, and it could go some way to helping solve the EU’s regional disparities. For over a decade, critics alleged that European fiscal agreements were too focussed on Germany. When Germany was strong and others struggled, that just reinforced structural inequalities, but now Germany is weak and, we suspect, will probably opt for some fiscal expansion under the next government.

This should not (necessarily) weaken the fiscal rules or approach for the whole bloc. German spending could mean previous laggards get an extra boost, from an already strong position. Europe’s economic troubles are undeniable, but markets seem to be ignoring the potential opportunities.