Published

18th December 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 18th December 2023

Central bank elves boost 2023 Santa rally

This edition of the Cambridge Weekly presents our outlook for 2024, which we compiled over the past two weeks. Inevitably, much of what we write depends on the starting point and this past week has moved that starting point markedly. This doesn’t make writing the outlook any easier, but at least the timing of publication means we do not need to revise our outlook already.

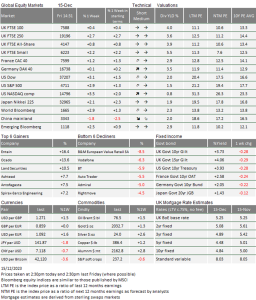

Looking back to a year ago, the introduction article to our 2023 outlook was titled: ‘Central bank scrooges cancel Santa rally’. One year can be a long time, and this year provided a very welcome Santa rally to end it. This means that globally invested, diversified investment portfolios, like the ones we manage for clients, should have once again, by and large, outperformed prevailing cash rates and consumer price inflation. Higher risk, equity focused portfolios in some instances should have returned even twice that.

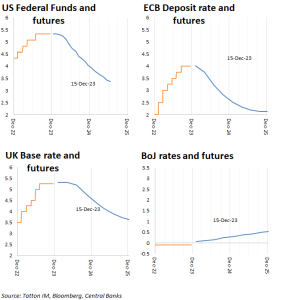

The gifts Santa brought markets were crafted by the central bank elves. Well, maybe Andrew Bailey and Christine Lagarde were less involved than Jerome Powell but at least they didn’t try to break bits off the gifts. Last Wednesday, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) did not move rates, but the market reacted almost as if it had announced a cut. Expectations of where rates will be across next year dropped sharply, with the first 0.25% rate cut now seen as underway by May and then rates being cut by 0.25% five or six times in total in 2024. The previous Friday, the first cut was predicted for June and three/four cuts for the year.

The shift in tone of Jerome Powell’s press conference comments after each of the last three Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) rate decision meetings has been the spur for changing market perceptions, given there have been no actual interest rate changes. We note that his authority with markets has increased, with investors lately hanging on his words almost as much as they did with the legendary Alan Greenspan in the 1990s.

Powell spoke of declining inflation pressures and, notably, an employment market moving into balance, which was completely unexpected. Given the unemployment rate had shown a fall from October’s 3.9% to 3.7% in November, this was an important assertion. Only at the beginning of the year, Powell had talked of the non-inflationary level of unemployment rate being 4.5%, so clearly, the FOMC’s view of what level constitutes ‘balance’ must have changed.

It is also interesting to note how the trading interlinkages of money markets mean that (for the time being) the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) currently have less impact on domestic interest rate expectations than does the Fed. Both held meetings last Thursday and, despite no rate move and only marginal differences to the October/November meeting narratives, rate expectations dropped before the meetings and stayed there as well.

Andrew Bailey did allude to “making progress” on the inflation front. Not surprising, since growth is anaemic for the UK as a whole, and November’s monthly growth was -0.3% which may well mean this year’s last quarter will show a small contraction. However, we continue to see a disparity between sectors; services remain supported, but manufacturing is worsening again, according to the CIPS/S&P Global purchasing manager index (PMI) reports. These showed the services PMI rising sharply to 52.7, a level which indicates services are back to a reasonable growth path; but it was not so good for the manufacturing PMI, back down to a nasty 46.4 and therefore definite contraction.

This dynamic was also the case in Europe until recently, but things seem to have changed and for the worse. The hope was for weak manufacturing to bounce but, unfortunately, service PMIs have shifted downwards to join manufacturing in the doldrums. Perhaps it is little wonder that despite the newly dovish mood music from the Fed, investors continue to see the ECB as the major central bank most likely to cut rates first, with the BoE not far behind.

Beyond the positivity from the service sector, we should also note that the UK is going through a bit of bounce in the housing market, now that 5-year fixed rate mortgages on offer have dropped back to around 4.5%. The housebuilders are up since the start of this last quarter by over 17%, currently beating every other sub-sector. And this is not confined to the UK, it’s interesting to see how house prices are also bouncing in other global regions.

Next year will probably be full of political drama. Hopefully, it will be the agreeable kind, borne out of a smooth democratic process. Major elections will happen here, in the US and many other major nations. Returning to the theme of central banks, it will not just be politicians having their records and behaviours judged. Having endured the almightiest inflation episode, central bankers may have decided to tread more carefully over this coming year, so as not to inflame sensitivities during a period of heightened political debate. This is not to say that they will develop biases, nor that central bankers will be self-serving. Rather, we should expect that their messaging will be less confrontational. Perhaps, if there is to be an impact on policy, it will be that they will prefer to act a little more quickly if inflation (especially wage inflation) allows.

On the back of the Fed’s sentiment change announcement, equity markets have in general had another good week. The exception was once again China. The western world’s elections are part of a system which spreads power and responsibility across many people and institutions, and thereafter holds them accountable for their actions in a transparent way. China has no such system and appears to be going through a crisis of confidence wherein its autocracy is a large part of it. Just over a week ago, Politico reported that Xi Jinping appeared to be purging his erstwhile lieutenants in a Stalin-like manner, confirming rumours we had picked up on the City grapevine. We cannot know the truth, but should hope that China is able to break this current spiral soon, so that confidence and economic sentiment can return to what is after all the second largest single economy.

This is our last full Weekly of the year. We wish you all the merriest of seasons and the best of wishes for 2024.

Outlook 2024

Heading into 2024, capital markets are in what feels like a contradictory position. Global growth has been slow (and in some places negative) for some time, while central banks have raised interest rates at the fastest pace in a generation. But despite all those challenges, equities have had a good year overall. With inflation finally falling, central banks are now loosening their vice grips, and bond markets are predicting a slew of rate cuts from the major players starting as early as March. That has pushed risk valuations in favour of equities and, perhaps more importantly over the long term, has even bolstered growth expectations.

If all these predictions come true, the coveted ‘soft landing’ – where financial conditions loosen without ever slipping into significant economic contraction – will have been achieved. This is about as good a scenario as investors could hope for, considering the plethora of ‘once in a lifetime’ events in the last few years. And yet, anxiety lingers. The rise in equity valuations has left stocks looking a little expensive, particularly in light of damp growth expectations in some regions. And despite the fact that no one seems to believe them, central bankers beyond the US are still toeing the official line that rates will have to stay higher for longer pretty much everywhere. Is the soft landing too good to be true?

To provide a view on this, we need a little recap. In economic terms, 2023 was (hopefully) the last chapter of our global inflation crisis. Stock markets took heart in this and delivered some decent returns, barring a couple of negative periods in the early spring and late summer. In sterling terms, global equities were up 10.8% year-to-date at the end of November, and the rally has only continued since. The flipside of this is that both of those negative periods were brought about by hawkish central bank policy and messaging. The consistent theme of this year has been that whenever markets look overexcited, monetary policymakers pour cold water over rate cut expectations. Ignoring what policymakers tell us has been a losing strategy all year.

The policy outlook has become the dominant driver of markets, and we expect this to continue for at least the early part of 2024. Swings in company profits are obviously still important, but they have been relatively small given the extensive yields and rates change context, and are thus having notably smaller impacts than in the past. Some of this is due to policymakers’ stated tightening bias making investors feel like ‘bad news is good news’; weaker company finances mean less inflation pressure and hence maybe lower rates. Valuations – stock price-to-earnings ratios and how these compare to ‘risk-free’ bond yields – have been thrashed about by changing rate expectations, creating significant volatility.

The sensitivity of equities to bond markets was on display just a month ago, thankfully (this time) for the better. In the last few months, inflation data has been tamer everywhere. This pushed up bond prices (the inverse of yields) and, a few weeks ago, stocks rose virtually in lockstep. In the last few weeks though, there has been a notable additional shift in market behaviour. Cyclical assets, like small cap businesses and European stocks, have powered ahead of large-cap peers. This suggests that markets are not only feeling good about interest rates but underlying growth too.

How these expectations play out will be crucial for markets next year. Ever since the financial crash of 2008, investors have been extremely sensitive to expected monetary policy, and 2023 was no different. This is historically unusual, but it could just be because – for most of that period – rates have been historically low. Rates staying lower for longer increases the sensitivity to rate changes because longer-duration assets gain

in relative value and thus make up a larger share of the market (the so-called duration effect). Now that real interests (inflation-adjusted, i.e. what is left after inflation is subtracted) have moved higher, it is possible we will see fewer valuation effects and more focus on earnings stability and growth.

Whether it plays out that way depends on why real rates have risen. This is a fundamental question and one that we cannot yet confidently answer. Low real rates are supposed to be the counterpart to high savings, but the rise in US real rates was accompanied by a savings glut, as trillions of US$ were invested in money market cash funds. Higher real rates could just be a shock response to spiking inflation – in which case we would expect them to come down as inflation returns to manageable levels. Investors seem to have something like this in mind when predicting a soft landing.

However, it is possible that the shock response has shifted the relationship between bonds and equities. Bonds are ‘risk-free’ only in the sense that governments borrowing in their own currencies always have the ability to pay back their debts. Historic bond market volatility over the last two years has plausibly made investors reevaluate the importance of the secondary risks of yield level driven valuation changes, and in particular how these compare to equities. At the same time, populism and geopolitical tensions have risen dramatically in the last decade – which has coincided with a seemingly structural widening of fiscal deficits, most notably in the US.

That would explain the apparent disconnect between real rates and other growth indicators. Traditionally, higher real rates suggest stronger growth expectations. Combined with high equity valuations, this would normally mean investors expect strong corporate earnings growth over the medium term. But that does not line up with the growth and earnings pessimism being reported from companies themselves – albeit mostly outside of the US. If investors have reevaluated the relative risks of bonds and equities, the old relationships may no longer be good guides.

This is why policy will continue to be the key factor for the first half of 2024 at least, but after that growth concerns might come to the fore. The growing disconnect between the US and elsewhere complicates matters, though. Growth prospects for the UK and Europe greatly deteriorated this year, while US powered ahead thanks to the incredible resilience of the American consumer. Now, with inflation plummeting, interest rates will surely follow here and in Europe. Across the Atlantic, however, and regardless of the latest Fed acknowledgment that rates have peaked, market expectation remains that looser policy there might take some time.

As we go through 2024, that could mean underperformance in the world’s largest economy – a reversal of what we have seen for years. If that happens, bond and equity dispersion will be joined by currency volatility. Such volatility makes firm predictions difficult. Looser monetary policy and (in the latter half of the year) an economic recovery in Europe are likely. Beyond that, unfortunately, we can only predict unpredictability.

Regions 2024

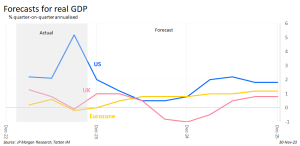

GDP growth outlook (as of 30 November)

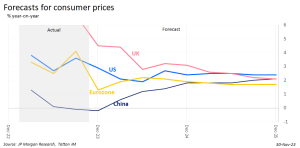

Consumer price inflation outlook (as of 30 November)

US

In contrast to 2023, the US economy might not be as strong as its global peers in 2024. Partly, this is about starting points; the US has grown more quickly than the rest, but that growth did not spread outwards in 2023. Next year could see US demand providing more external support. In addition, we think that past strength is likely to keep the Fed relatively less accommodative than other central banks (despite investors perceiving a dovish shift in the Fed’s policy following the December 2023 meeting). This could mean underperformance in US markets relative to Europe or even Emerging Markets. Currency volatility may result, perhaps continuing the recent trend of dollar weakness, which is again generally a growth positive for the global economy.

The US was indisputably the standout performer this year. Price pressures (Europe), weak consumer sentiment (China) or both (UK) severely hampered growth across most of the world, but the US economy proved surprisingly strong, mostly thanks to the irrepressible American consumer, buoyed by remarkable job security. This meant US equities once again outperformed other markets. The benchmark S&P 500 index is up nearly 22% year-to-date (in dollar terms) at the time of writing. The performance of big tech was even more impressive and responsible for the majority of the overall market return. So long the darling of retail investors, mega-cap tech companies were boosted yet again by the artificial intelligence (AI) investment phase. This is all the more remarkable considering interest rates continued climbing and will finish the year touching 5.5%, the highest level in 20 years.

The so-called ‘excess savings’ built up during the pandemic is what kept consumer demand, and hence overall growth, strong for so long. Excess savings are a bit of an odd theoretical concept (the total amount resulting from the difference in post-pandemic and pre-pandemic trendlines over the pandemic period) and no one is exactly sure how to measure them – but everyone agrees that Americans have dipped into their excess more than anyone else.

At the same time, US economic and financial dominance mean it continues to attract foreign capital. Its pull has been in overdrive ever since 2017, when then-President Trump’s tax breaks and trade wars led to a wave of capital repatriation. The process continued in 2023, thanks to anti-China sentiment from the top (the Biden administration) to the bottom (grassroots investors). Excess savings and capital pull have left the US swimming in liquidity – helping asset markets and the underlying economy. The Fed has tried to soak up this liquidity with its restrictive policy, but there is plenty still left – evidenced by the relative looseness of US financial conditions.

There is a strong case that this has pushed the US into bubble territory. Goods and labour are significantly more expensive in the US than elsewhere, particularly in the big cities. Much of this is backed up by stronger growth and productivity, but this will inevitably moderate when excess savings dry up – which could be very soon, according to some analysts. Government programmes have invested in productivity, but the fiscal deficit is large and set to rise significantly with interest costs. There is also the small matter of a presidential election next year, which is likely to bring further spending promises and plenty of political instability. That being said, energy – especially natural gas and electricity – is much cheaper than in Europe and nowhere looks ready to match the depth and dynamism of the US economy.

This means the US might become the victim of its own success in 2024. The liquidity from the pandemic period still is yet to be worked off. Meanwhile the lagged impacts from the pandemic-inspired loose fiscal stance are likely to keep the Fed from cutting rates as early as the European Central Bank (ECB) in Europe, even though growth is weakening. Markets seem to have a rosy view of Fed policy at the moment and so could end up disappointed. In our view, interest rates are likely to come down in Europe (and possibly even in the UK) before the US.

JP Morgan research predicts these factors will bite in the second half of the year. At that point, Fed policy will have sucked up most of the excess liquidity while real disposable income growth may be slowing (possibly as wages growth slows but goods deflation lessens). We may even see the US flirt with recession. If so, currency volatility and, hence, wider market volatility, is likely.

UK

Monetary policy is perhaps the most important part of Britain’s outlook for 2024. Despite the perceived hawkishness of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), we expect interest rates to come down, thanks to inflation finally falling back to target. If we are right, that will be broadly supportive for UK assets, although any earnings-driven upside may be limited, thanks to damp growth prospects. The start of a new growth cycle is likely to coincide with a General Election – which could bring new public investment. However, government finances are constrained by budgetary concerns and political will, so we should not expect too many growth prospects to come from that avenue. In the end, Britain’s 2024 is likely to be like its 2023: mildly positive, but ultimately middling.

UK inflation was higher and more persistent than in the US or Europe for all of 2023. This led to a perception – seemingly shared by the BoE – that Britain had a particular inflation problem and therefore needed particularly restrictive monetary policy. The rationale for this is that the UK’s supply side was battered by both Brexit and the pandemic and never fully recovered. BoE officials have firmly denied there is any room to cut rates soon.

As we wrote recently, this ‘Britain struggles alone’ narrative is questionable. BoE officials have used sticky services inflation as evidence that UK price pressures are “home grown”, but sticky service inflation and tight labour markets are true across the western developed world. Moreover, we now see definitive signs that UK inflation has fallen in line with elsewhere. Given the rhetoric coming out of the BoE, policymakers are unlikely to cut quite as quickly as European counterparts. But falling inflation will inevitably force their hand, and rate cuts should be underway by the summer.

This will mean falling bond yields and a pick-up in equity valuations. UK equities are notably cheaper than global counterparts on a price-to-earnings basis, reflecting years of neglect by foreign investors. Valuations have plenty of room to climb and – since we expect positive bond market movements – Britain looks good value.

Next year will almost certainly see another General Election (though the latest possible date is January 2025, which is unlikely but cannot be fully ruled out) which, barring an historic turnaround, is likely to deliver a Labour government. Given Keir Starmer’s cautious approach, though, we do not think this will dramatically change medium-term growth prospects or financial conditions. There are some hopes that trade negotiations with Europe might be improved by a structurally less antagonistic government, but any effect from this will likely be long in the future.

Overall, it will likely be slow and steady for UK investors, but starting from a low base will help.

Europe

Economic weakness should mean supportive European monetary policy early in 2024. With any luck, and with the global economic tide potentially turning, this could translate into stronger growth in the second half of the year. These cyclical factors, combined with the relative cheapness of European equity versus the US, should mean market outperformance as of late, but risks remain. There is a risk that the ECB has overtightened already, throwing the fragile economy into deeper recession than needed. On the other hand, the continent is still recovering from its energy price shock and the fiscal deterioration it brought. We do not think these factors will disrupt what is ultimately a positive story, but we must stay wary.

This year was the tail-end of Europe’s worst supply disruption since the second world war. Such an intense shock, so soon after the pandemic shock, inevitably leaves scars. Not only have businesses and households cut back, dampening growth prospects, but national budgets have deteriorated in response to emergency subsidy spending measures and sharply higher borrowing costs. Germany, the Eurozone’s historic powerhouse, epitomises this. German businesses are incredibly weak across both manufacturing and services, but the government is unable to support the economy due to its own finances. In the run-up to Christmas, the government narrowly avoided shutdown, by agreeing a €17 billion funding deal, which included spending cuts for ailing industries.

Germany has particularly tight fiscal rules which prevent it from spending (evidenced by November’s court ruling that Berlin’s spending plans were unconstitutional), but there is a general pattern of fiscal tightening across the continent. This is mainly drag from previous spending episodes, including on defence measures resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We expect tight fiscal policy to be a feature of most major regions in 2024, but probably more so in Europe.

That only increases the urgency of the ECB’s rate cuts, which are now a matter of when, not if. Headline Eurozone inflation fell to 2.4% year-on-year in November, while core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy) has been on a downward path for months. Markets have subsequently brought forward their rate cut expectations to as early as March. And even then, many commentators are suggesting the ECB is once again ‘behind the curve’ on inflation – only this time in reverse.

Expected cuts and tighter fiscal stances have driven down bond yields dramatically in recent months. At the time of writing, Italy’s 10-year yield (a benchmark for slightly riskier European debt) is below 4%, its lowest level since February and below even the US. With equity valuations still low (compared to US markets) there is plenty of room for valuation-driven upside in the first half of 2024. That upside will hopefully be bolstered by returning growth in the second half of the year. With so much gloom around the Eurozone economy, growth optimism may seem strange. But looser monetary conditions and a recovery in global growth are sure to benefit the Eurozone. European equities are some of the most cyclical there are; the start of a new cycle should serve them well.

Emerging Markets

If our central scenario of a global cyclical recovery and weaker dollar plays out, Emerging Markets (EMs) stand to benefit in 2024. This would be helped by a Chinese economic recovery, particularly if consumers there felt confident again. This is certainly possible, but investors have been burned by China before. With the inherent economic and financial risks surrounding the world’s second largest economy, EMs would do well to focus on securing their own prospects. Fortunately, this is already underway, particularly for regions like Brazil that sorted their inflation problems early.

This year was understandably challenging for EMs. Generally considered ‘risk-on’ assets, EM bonds and equities were starved of foreign capital due to restrictive central bank policies in developed nations. Rate hikes and growth outperformance in the US pushed up the relative value of the dollar – hurting EM businesses and governments with dollar-denominated debts. Against that backdrop, Chinese domestic growth was supposed to be the one shining light, providing EMs with much-needed demand. But China turned out to be the biggest growth disappointment of the year – struggling under the weight of a property crisis and without the apparent political will to push through it.

Lately, the signs are that all of these trends are reversing. While monetary policy is set to get looser, US outperformance is likely to end, for reasons discussed above. This should put pressure on the dollar, something that has already begun in recent months. Meanwhile, it is clear from recent announcements that Chinese policymakers are reprioritising growth.

For China, the main question is now not whether Beijing is willing to soften its deleveraging stance and promote growth, but whether it can. Private sector business confidence appears to have plummeted when one looks at market-based indicators. While government borrowing is now rising, private sector borrowing continues to decline. The recent spike in consumer default numbers, and the weak pricing power for goods exporters, suggests it might not be so easy. Even with central government support, we expect China to radiate disinflation for at least the early parts of 2024.

While a Chinese demand shortfall helps no one, disinflation might at least be a boon for some EMs as it allows their central banks the room to loosen monetary policy and bolster their own domestic growth. We see this in Brazil, where inflation is largely under control and its central bank has already begun loosening. ‘Evil twin’ Argentina is obviously in a less comfortable position – but we will reserve judgement on the new president’s dollarisation plan for now.

The green shoots of a global recovery, if and when they show, should boost sentiment around EM assets. But with the global economy in such a precarious position, 2024 will likely be another year where differentiating between EMs is key.

Asset classes 2024

Bonds

In line with our expectations for government and central bank policies, we expect bond market dispersion in 2024. Despite ECB President Lagarde indicating a continued bias towards tightening, a mild tightening in fiscal policy, softening wage rises, energy price falls and generally lower inflation should allow interest rates to fall sooner in Europe than in the US. That is likely to mean a widening of the gap between US and European yields in the early part of the year.

The gap between long and short-term government bonds could widen as investors re-evaluate the relative ‘term premia’ risks (a measure of the likely benefit of holding long-term bonds relative to cash). We saw this particularly in the US during the autumn, when investors wanted to be paid a higher yield for taking the long-term risk of future yield level changes. The supply of US government bonds will continue to increase relative to other nations over the next few years, and we think there might be occasional repeats of the autumn 2023 yield jumps, with at least another next year.

Such an occurrence would cause some disruption, and to corporate bonds as well. But investors clearly have faith in broad financial stability, so any move up in credit spreads (the difference between government and corporate bond yields) will likely be seen as a buying opportunity.

This past year was very much a mixed bag for bond traders. There was a prolonged sell-off in most major developed economies in the middle part of 2023, but this has sharply reversed since October. Markets are convinced we will see meaningful interest rate cuts next year, even though some central bankers keep toeing the ‘higher for longer’ line. Implied market expectations are that rates will be roughly a whole percentage point lower than current levels in both Europe and the US by the end of 2024, but only 0.5% lower in the UK.

Among major markets, Japan is the only exception: traders discount a 0.2% rise in Japanese yields. The stark difference in Japanese bonds reflects the starkly different economic challenges, with low growth and disinflation still the main issues Tokyo must address. Continuing the trend we have seen for many years, Japan’s economic fortunes are much more closely tied to China – whose inflation and government bond yields are similarly low relative to the west.

For the west, rate cut expectations mean that yield curves (the plot of government bond yields at different maturities) are still inverted. Historically, inverted yield curves have often been good indicators of upcoming recession, but this does not line up with other growth indicators. According to JP Morgan, for example, each major region is growing – albeit a little sluggishly – and going by rate cut expectations, we are on the cusp of a starting a new growth cycle.

It is interesting that the UK has the smallest rate cut priced in (compared to the US and Europe), considering it is the most likely (on economic indicators) to experience a recession. As we point out in our UK-specific outlook, we think inflation will probably fall in line with Europe, enabling the BoE to reconsider its hawkish stance. From that perspective, UK bonds start the year showing some value, even considering the recent sharp fall back in yields from October.

US bond yields are currently higher than in the UK and even Italy, and yet we still think they look a little expensive. This is primarily because of the US’ inflation impulse, emanating from its resilient economy. Looking at the economic fundamentals, we think it unlikely that the US will deliver as big a rate cut as the Eurozone in 2024, and yet that is exactly what markets currently suggest. On top of that, the US fiscal deficit is wider than elsewhere and the gap is likely to widen as we head into an election year. New US Treasury issuance has impacted bond markets significantly this year, and we expect the same in 2024.

Shifts in the long-term risk premia – how long-term bonds are valued against short rates – have become more prominent in 2023. These have fallen sharply since October, dropping below historic averages. With inflation still lingering, we expect them to move higher in 2024 – primarily in the US. Relative risk valuations will impact credit spreads too, but these have thankfully been resilient. Even though growth is weak (and in some cases negative) investors do not seem to fear widespread bankruptcies or financial instability. That is good, since it will likely mean a ‘buy the dip’ mentality in corporate bond markets.

Equities

For most regions, historically cheap valuations, loosening monetary policy and the promise of a new growth cycle will benefit stock prices in 2024. The only exception to this is the US, where equity valuations look stretched following yet another year of outperformance. It could mean a reversal of US dominance, particularly if US rate cuts lag the rest of the world as we expect.

The strength of the US equity market, much like its domestic economy, has been unparalleled in recent years. In particular, the outperformance of the US mega caps was stunning in 2023. Share prices for the so- called ‘Magnificent Seven’ – the most highly valued companies in the S&P 500 – increased by more than 70% in response to the generative AI investment craze, while the remaining stocks in the S&P gained just 10%. Whatever the justification for this outperformance, it means the US continues to be more expensive (on a price-to-earnings basis) than anywhere else.

Much of this is likely down to shifting behaviour of US investors themselves, who have become much more inwardly focused – and now tend to prefer passive investment strategies. In 2012, passive equity funds made up about 30% of US stock funds, but that has now grown to 60% according to Bloomberg. At the same time, the US share of global public equity funds has grown from 47% to 61%. Britain’s share, by contrast, has fallen from 7.5% to 3.5%, while European equity has dropped from 16% to 13%.

Not only are American investors buying American, but the revenues of global companies are increasingly sourced from the US. It creates a feedback loop of American consumers – among the wealthiest in the world – funding company profits through their spending, then gaining the money back through stock ownership. Foreign investors have bought into the story too, and as the years have gone on it has looked increasingly like a bubble. The difference this year is that US bond yields could diverge from Europe and, given yield moves have been the biggest source of equity volatility through 2023, this is likely to be a source of return dispersion between regions.

Comparatively, British and European stocks are trading at cheap valuations. This is certainly true for the UK, whose attractiveness as an investment destination has been in decline since before Brexit. These, historically relatively cheap valuations are still a little pricey in absolute terms, at least for where interest rates are. But Europe’s rate cuts are effectively confirmed at this point, while we have argued elsewhere that the UK must follow suit. If global growth is stronger than expected, British and European equities stand to benefit.

The rest of the global equity picture is mixed for 2024. Improvements in Japan’s corporate structures have gone under the radar in recent years, but it is clear that companies and shareholders are seeing the fruits of structural change. Margins are improving (from admittedly low levels) and Japanese workers are among the cheapest in the world for their skill levels. Any pick-up in exports (which can only come from a global cyclical rebound) will likely have second-round effects on wages and domestic demand, making Japanese stocks a worthwhile bet.

Despite being economically linked to Japan, China’s stock market is at the opposite end of the sentiment spectrum. Policy disappointments and property market woe have led to an exodus of foreign investors. Given the ongoing tensions with the US and western media’s description of China as ‘uninvestable’, foreign capital will not come back in a hurry – despite the government’s undeniably supportive policies. That being said, Beijing has never been under the illusion that it can rely on foreign investment over the long term, and the reinvigoration of domestic consumers and investors is key to unlocking China’s strong growth potential. The ingredients are there, and the Party clearly wants to make it work. The question now is whether it can.

Currencies

Assuming our policy and economic outlook holds up, the US dollar should decline in 2024, but with bouts of volatility in currency markets. Foreign exchange rates are some of the most unpredictable areas of finance (and are in some cases provably random) so currency predictions can feel a bit like having a strategy at the casino. But the dollar has become undeniably expensive over the last few years – thanks to impressive capital flows into the US – and this process has to stop at some point. There is every reason to think that point will come next year.

The dollar dominates currency discussions because most of the world’s trade is conducted in the US currency. It generally falls when companies with large dollar revenues but non-dollar payouts (including profits) do well, and it generally rises when companies with dollar liabilities struggle to finance them. In 2023, global trade was muted but dollar liquidity was stable. As such, the dollar will end the year more or less where it began – though this is expensive by historical standards. Sterling and the euro were also stable, but at historically cheap levels, while Japan’s yen notably cheapened relative to what you would expect from trade flows. China’s renminbi fell too, but not by as much as publicised weakness would have you believe, and other emerging market currencies were impressively stable – thanks to institutional improvements in many EMs.

As noted in our US outlook, the US has been dragging in global capital for years. As such, the dollar is valued highly against global currencies compared to history. That trend might finally unwind in the coming year especially if US growth falls below its peers. In the best-case scenario, global growth rallies thanks to rebounds in Europe and Asia. But even if that is too optimistic, the US is just not likely to live up to the growth disparity that relative currency valuations would seem to imply. Even a mild outperformance from outside of the US would likely cause some capital outflow, lowering the dollar’s value. The Japanese yen could be a particular beneficiary – considering its current cheapness on a purchasing power basis.

Commodities

Commodity prices – oil and gas in particular – will probably stay weak into the start of 2024. As the year goes on, though, global growth expectations should shift. Global growth usually means stronger commodity demand, so prices should be supported. But the amount of support depends on many factors, like where growth is expected to come from and in what form. China will likely be a bigger source of commodity demand – at least compared to how it has been for the last few years.

We end 2023 with oil prices down year-to-date, following a substantial decline from the autumn. Energy generally has cheapened, following sharp increases in fossil fuel output. Non-OPEC sources of oil and gas have been particularly busy, including producers in the US – many of which are taking advantage of the fossil fuel renaissance to buy up competition. Cohesion among OPEC+ nations is clearly faltering – with Russia in particular needing to pump out its fuel for war funding. Putin’s Ukraine invasion shook energy markets and sent prices skyward two years ago, but the global instability he wrought is now having the opposite effect. Demand is weak and the cartel cannot effectively control supplies.

The imbalance has longer to run if global growth forecasts are to be believed. Outside of oil and gas, metals have slowly lost ground – with the exception of iron and steel. This will not turn around until growth recovers, which is unlikely before the middle of 2024.

The biggest demand swing could come from China, whose government has made clear it prioritises consumer demand and building activity. If Beijing keeps revving the economy, prices for commodities in general will be well-supported. In this sense, we should keep an eye on commodity prices, as these could signal a wider recovery.

Property

There is potential for a property rebound in 2024, but whether it happens will depend on policy. Residential property – both houses themselves and housebuilders – have already turned positive into the end of 2023, and this is likely to continue at least for the start of the year. Whether prices can keep rising will depend on central bank policy and, later, on governments’ willingness to commit to building projects and easing of planning restrictions.

The past year has been difficult for residential property, but activity has picked up across the world – even in China’s ailing building sector. This happened after the fall back in long-term bond yields, which suggests current rates are cheap enough to spark building activity.

Commercial real estate, on the other hand, is still in a clearing phase. The stable, post-pandemic level of demand for retail and office space is not yet clear, while input costs (including insurance) are also in flux. The end of 2023 has seen European real estate investment vehicles come under pressure – a trend that will likely be repeated across the world.

However, the settlement prices for current property deals are cheap enough to entice buyers – considering recent yield declines. This suggests a floor for property prices, assuming there are no further shocks. But significant increases from this floor will be hard to sustain without extra support. Borrowing rates are still high compared to recent history, and central banks will not want to cut rates by more than what markets have priced in (which is already more than what central bankers have admitted to, it should be said).

The biggest hope for property prices is government building policy. Next year will see nearly half the world’s population go through elections, and building is an easy sell for most politicians. In multiple regions, we have already seen suggestions of looser planning regulation. This has the potential to unlock substantial amount of growth for the wider economy. Prospective governments might see this as an easy win, considering that many building projects are at least partially funded by private groups, lowering the spending that appears on their balance sheets.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.