Published

15th January 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –15th January 2024

A bumpy upwards path ahead

Every hangover comes to an end, and the equity market’s malaise lasted no longer than usual. After refusing to get out of bed the previous week, last week the markets decided to go to work. Europe recovered the previous week’s losses while US indices moved ahead smartly. However, softness in global banks hit the UK Large-Cap index as did a continued pullback in energy and materials sectors (that is, the more commodityrelated companies).

The standout performer was Japan, where investors appear convinced that a corner has been turned. As widely reported in the financial media, the Nikkei 225 reached – and exceeded – the high of 1990 even if its actual all-time high of 38,916 was reached at close on 29th December 1989, the height of the infamous Japanese stock market bubble. That’s another 10% away from today’s level, but investors have got the bit between their teeth and so now such a move looks entirely attainable.

Interestingly, it appears to be driven by domestic as well as international investors in this phase. The good performance of previous months was accompanied by small bouts of yen appreciation, but January’s move has occurred while the yen has eased against the US dollar. Japanese investors have not been happy supporters of their own domestic companies in recent years (with good reason), but they may be changing their view. A bout of self-confidence may have positive impacts for Japanese stocks.

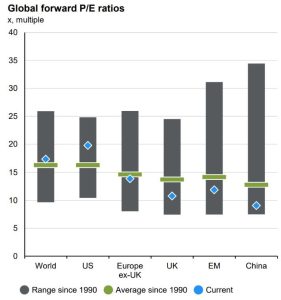

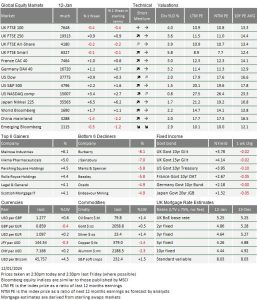

The December rally in equities and bonds was, from our observations, driven by the remarkable shift in investor sentiment – we reported at the time – which unleashed flows of idle liquidity more than anyfundamental change in the macro-economic landscape (yet). And of course, December is a quiet month for earnings reports so there was little change in underlying earnings. Across the world, valuations (such as price-to-earnings ratios, even when using analyst expectations which include next year’s anticipated growth) are slightly expensive within the historical ranges, and they are expensive in the US (note the blue diamond above the green bar for World and US in the chart above).

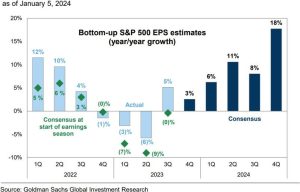

Against this backdrop, as we enter earnings season, companies will need to report lots of surprisingly positive Q4 earnings and solid outlooks in order for equity prices to rise substantially from here. Yet, that’s perfectly possible. Investors know that analysts can easily prove not to be optimistic enough.

The biggest issue is that company share prices do not go up just because the current share owners want it. Even with good news, there has to be somebody else to bid to buy the shares. A company may reveal higher earnings than expected, but the prospective new owner has to be convinced that either the current valuation is now cheap, or that the positive earnings indicate a faster growth in future earnings.

When positioning becomes extended, it can mean there will be less additional interest and so fewer prospective owners willing to bid prices higher. On a historic comparison basis, this seems to be the case with Goldman Sachs, noting that US equity futures’ outstanding investor exposure now stands near record highs of almost $160 billion, and that momentum funds are positioned towards 2023 highs. Furthermore, their GS Sentiment Indicator, which tracks position across more than 80% of the US equity market owned by institutional, retail and foreign investors, is likewise indicating high levels of investment noting at very extended levels versus its long running average (in mass terms by +1.2 standard deviations). JP Morgan (JPM) noted that many risk appetite measures are back at bullish late-July levels. Bank of America’s Bull & Bear Indicator ticked up to 5.3 from 5.0, the highest since November 2021.

Meanwhile, although issuance of new corporate bonds slowed a little recently, corporate bonds as an asset class overall appeared to get a big infusion of investor capital. On the back of the strong demand, alongside equities, corporate bond yields fell somewhat, compressing spreads (the premium corporate borrowers have to offer above the government) in the US corporate market to levels which have marked a low over the past 25 years. One can conclude from this that fears about a near-term recession have not just ebbed, they have effectively disappeared.

Against this backdrop of positivity, the risk for asset prices is unlikely to be about current earnings or their future growth. Indeed, valuations in equities and spreads in bonds tend to be quite stable over any mediumterm period. However, in recent times, equities and corporate bonds have performed less well when government bond yields have risen – and this is where the risk lies for the coming weeks.

As laid out at the beginning, the last quarter’s fall in government bond yields was largely the driver of valuation rises, but now yields appear to have bottomed. The inflation picture has stopped improving for now, with last week’s data from the US and the Eurozone being somewhat higher than anticipated. We cover some aspects of the story in an article below.

Geopolitical risks also continue to bubble. At the weekend we had the Taiwanese elections and the incumbent governing Democratic Progressive Party with current vice president William Lai (Lai Ching-te) declared victory on Saturday evening. The FT reported that “Joe Biden plans to send a high-level delegation of former top officials to Taipei after the election in Taiwan on Saturday, a move that could complicate efforts by the US and China to stabilise their strained relationship”. We don’t think it is in anybody’s nearterm interest to provoke action, but this week may see rather unsubtle posturing, which might present some risks.

China’s markets are most at risk due to the poor domestic investor sentiment there and they have as a result already been poor performers. Recent news flow has made little impact on domestic equity markets, so we don’t view predicting any link between event and share price outcome as a worthwhile activity. However, at least one large investor introduced a note of positivity, putting on a very large call option trade last week. This gives them substantial medium-term exposure to potential China share price rises. That’s an interesting move, given the proximity to the election.

The next (scheduled) globally important election will be the biggest ever seen. In June, India goes to the polls to elect its members of parliament and Prime Minister. We have dedicated a separate article this week to write about Modi’s second term and some implications for the further modernisation upside that investors are currently contemplating.

The last few months tell us of rising investor confidence. Household/consumer and business confidence is showing early signs of turning upwards, and this positive combination augurs well for risk assets. The key question though, is whether positive growth will be gentle enough to keep prices stable and allow central banks to cut interest rates before the summer as markets have thus far anticipated. The next round of central bank meetings begins with the European Central Bank on Thursday 25th January, with the Fed and Bank of England meetings scheduled for the following week. Given how much market fortunes have been tied to interest rate and yield levels over the past two years, yet again it is the central banks, and not so much the underlying economy, that will determine the direction of market travel over the coming quarter.

Central bank watchers will be in heavy demand over the next two weeks.

Is disinflation transitory?

The capital market rally into the end of 2023 was all about inflation and, more specifically, its retreat. After the pandemic price spike, last year offered clear reprieve. Goods prices cooled significantly, led by falling energy prices, while tight labour markets loosened, and service inflation fell in the second half.

The disinflation trend excited investors for two reasons. First, weaker price pressure is a precursor to interest rates falling from their highest levels for ten years. On cue, dovish signals from the major central banks – led by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) – started the rally in late Autumn. Second, lower rates and inflation mean the economic growth cycle can start anew. This expectation was clear in the outperformance of cyclical assets – like European equity, or small and mid-cap stocks – into the end of the year.

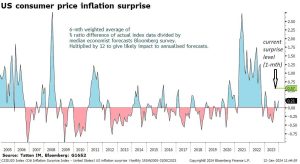

Inflation expectations are therefore key to the investment outlook for 2024. But there are already suggestions that markets may have got overexcited about the likelihood that inflation continues to decline at last year’s pace. Last week’s release of December’s consumer price index (CPI) numbers from both the US and Eurozone were higher than economist expectations.

Eurozone inflation had dropped to 2.4% in November, but rose to 2.9% in December. However, inflation pressures are more apparent in the US, where the year-on-year (yoy) overall CPI rate rose from 3.1% to 3.4%, above the Eurozone. Moreover, US CPI inflation bottomed at 3% in June, with the sharp decline occurring in the first half of 2023.

For the US, the shorter-term pace is now showing signs of accelerating, especially in the ‘core service’ components. Core service prices were up +0.4% (+4.8% yoy annualised) last month, with rent increases moderating only gradually. Core services ex-rents (known as ‘super-core’) were also +0.4%. Medical care service prices were up a firm +0.7% last month, driven by health insurance cost increases.

Current short-term bond prices, which reflect short-term inflation and interest rate expectations, imply inflation in the US and Europe will settle at or below the 2% central banks’ target within two years. But a quick look at recent headline inflation figures suggests the path down could be bumpy.

Headline inflation figures are inherently backward-looking and can be misleading, which is why central bankers look at the previously mentioned core measures (which exclude volatile inputs such as food and energy) or alternative indicators of activity. Lower core goods prices were the main factor behind falling inflation in the second half of 2023. Supply chain pressures that marred the pandemic era economy went into full reverse, resulting in 1% annualised deflation in core goods prices for the three months to November – according to research from JPMorgan (JPM).

In that research note, though, JPM argue this trend has come to an end. The graph below shows actual US CPI inflation data as a ratio of median economist forecasts (surveyed by Bloomberg). When the graph is in the positive, economists will have underestimated the actual rate of inflation (2021/2022). During 2023’s sharp inflation declines this reversed and then more recently has once again disappointed prognosticators with less declines than anticipated.

The track for core goods prices has shifted up in recent months, as inventories have depleted, and supply overhang has worked through. A good example is the increase in air and freight shipping costs. These shot up during the pandemic supply chain crunch, and fell back dramatically when goods prices eased, but are now on the up again.

In recent data, we have seen signs that the overhang in goods inventories – one of the biggest factors behind deflation for end goods – has cleared. We are now seeing general signs of a tightening in global supply chains. The most recent survey data from manufacturers shows that companies are feeling more confident about their own prospects for output prices and delivery times.

There is some concern that supply chain disruptions are re-emerging (with certain ports having rising backlogs of goods waiting to be shipped, as well as the Suez and Panama Canal disruptions) but, currently, these pressures are only mild and do not point to another price spike for core goods (see shipping freight cost index chart below). Nevertheless, they show that the key disinflationary force we relied on for months has dropped away.

This is nothing out of the ordinary; the push and pull of the global economy usually means that trends jump from sector to sector. Indeed, the high inflation period started in goods but spread to services – and goods inflation was already turning by the time service inflation really picked up. The key question, then, is whether services can keep overall disinflation going now that goods have turned.

JPM’s researchers think not. Service sector inflation has proven hard to tame so far, kept high by a structural shortage of labour – and hence higher wage pressures – across most of the developed world. According to their research, developed market wage inflation ran above 4% in 2023 – double the pre-pandemic average. And while service inflation (much more sensitive to wages than goods) fell from its 6% peak in early 2023, it has stabilised at a 4.5% annualised rate, again double the pre-pandemic trend.

The path down for service inflation has already been noticeably less steep than for goods. This seems to be down to the different structural factors affecting each sector: while goods producers were severely hampered by supply chain congestion, and a once-in-a-generation rearrangement of global energy markets, these forces are inherently time-limited (even if they lasted much longer than anyone hoped). We do not yet fully understand what caused the global phenomenon of tighter labour markets (Covid and antiglobalisation clearly had an impact, but exactly what impact is still hard to determine), but it increasingly looks like it is here to stay. There has been some loosening – with job vacancies rising – but things are still tight, and the rate of change does not suggest any imminent drop-off.

JPM, among others, have suggested this means disinflation is just “transitory” – a wry nod to the wrongheaded predictions people (including central bankers) made about inflation coming down shortly after it first rose. If that is the case, bond market expectations are wrong and, crucially, central banks might not cut rates so soon after all. This would undermine the main rationale for recent market positivity and hence threaten a sharp reversal. So, is disinflation transitory?

It is impossible to answer for sure, but we can say a couple of things with confidence. Firstly, the recent equity rally certainly makes stocks vulnerable to a short-term correction if there are inflationary signs. These might not come – and we have argued that China’s disinflationary impulse is a huge but often-ignored factor. But if they do, current valuations look vulnerable in the short-term – even if they are fair for the longerterm picture.

Secondly, the answer varies dramatically by region. The US market has been investors’ darling for years, and the Fed led the way in signalling rates easing this year. But the US economy also has the tightest internal labour market – its surprising strength in 2023 came from this fact. Europe, by contrast, has much lower equity valuations, even after recent outperformance. Core service inflation in Europe has also been surprisingly weak – particularly compared to the US. This side of the Atlantic, services look much more likely to pick up the disinflation slack.

While we are not blaring the warning sirens about “transitory” inflation, it is certainly something we will have to watch closely as we start the year. The early winter rally – and market excitement about disinflation – has set the scene for disappointment in at least some assets. Judging which ones is crucial for the year’s investment outlook.

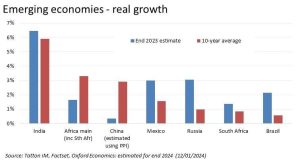

India’s stalling course of reforms

Among Emerging Markets (EMs), India is something of a firm favourite for UK investors. The reasons may seem obvious: it is the fifth-largest country economy in the world and is growing faster than any of those above it on the list. It has strong economic and financial ties with developed nations – a particular draw for UK investors – but its financial and corporate structures still have plenty of room to improve. More recently, India’s stock market also benefitted from EM investors dramatically reallocating their capital away from the disappointing China. This led to a 20% jump in the Nifty 50, India’s headline equity index, in 2023. The index has doubled since the start of 2019.

Rapid development underpins India’s status as a hotspot for foreign investment. This is not just economic development – impressive though it is – but also institutional, financial and political development. Investment decisions are impossible without knowledge of, and faith in, the underlying rules and governance structures, which is why positive reforms (in particular for western investors, market-based reforms) are a good sign for EM investors. In this sense, India’s path in the last two decades has been remarkably similar to China’s between the 1990s and 2010s – a strengthening of corporate governance, opening up of asset markets and closer alignment with western-style international trade rules.

This reform agenda has been at the heart of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s two terms in office. In his first term, the reform drive included high-profile episodes like introducing a singular Goods and Services Tax (GST – a VAT equivalent replacing many different state-level taxes), removing foreign investment limits across various sectors, and the controversial demonetisation of high-denomination banknotes, in exchange for a big push in digitalisation and accessibility of online banking and payment processing. His second term has had fewer big-ticket reforms, but has included the privatisation of Air India, and numerous corporate tax cuts. Free market reforms are the main reason for western investors’ generally favourable views of Modi, despite his and his party’s anti-democratic and far-right social policies.

His second term is set to end in a few months, after Indians go to the polls in the April-May general election. Even though Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) is overwhelmingly expected to win, the election is sure to intrigue. Indian elections are a fascinating democratic exercise: the world’s most populous nation, with 1.43 billion people, millions of whom live in poverty, splits up the voting over a number of weeks, mostly by region. The 2019 election happened in seven phases, during which 603 million people voted (including a record number of women). Those votes translate to just 543 parliamentary seats, awarded on a first-pastthe- post basis. Five years ago, the BJP won a landslide with the highest vote share since 1989 – but that came in at just 37.36%, or 229 million out of 912 million eligible voters.

It would be hard, though not impossible, for the BJP to repeat or better that performance. Modi is popular even after nearly a decade in charge and some highly unpopular policies (like the initial reaction to demonetisation) – in large part thanks to improving economic conditions. The share of Indians in poverty has fallen (though this trend has stalled in recent years – even before the pandemic), while India’s middle class has greatly expanded. But extending political gains this far into an administration is always a challenge.

If the BJP loses seats, reforms will be harder to implement. This is particularly so for altering or removing labour market protections and privatisation. In the unlikely event the BJP loses to a centre-left coalition, short-term labour reforms will be extremely unlikely – even if the longer-term alignment with western institutions continues. These free-market reforms were what excited foreign investors over the years, so re-evaluation might be in order.

In fact, the next government is unlikely to come bearing gifts for foreign investors – even if the BJP increases its power. For all the talk about Modi’s reform agenda (his allies promised a slew of labour law changes and privatisations within months of his second victory), his second term has been underwhelming. Air India was the only major privatisation, and most of the planned changes were either cancelled or held up in political procedure.

That Modi could not achieve his stated aims with a massive parliamentary majority shows the strength of the old status quo. Landowners and agricultural groups hold a lot of political sway, while many politicians have vested interests in keeping certain large enterprises state-owned. On top of this, the lack of reform shows a change in political priorities. When Modi came to power a decade ago, free-market liberalisation and the attraction of foreign capital were top of the agenda. But after ten years at the helm, he is arguably more focused on pandering to his voter base. This will likely mean an even greater focus on Hindu nationalism and antagonism toward non-Hindu populations.

The BJP’s populist agenda means that privatisation and fiscal conservatism – which Modi claims to be in favour of – will inevitably fall by the wayside, particularly in an election year. The ruling party has already promised the same fiscal support as the opposition, at a time when the fiscal deficit is huge by historical standards.

On the reform basis alone, then, foreign investors have little to get excited about in 2024. But India’s equity market success is also propelled by economic optimism – which is likely to carry on for the time being. Moreover, Indian assets are supported by production reallocation from China, whose risks are still very apparent. Whether those flows will continue later through the year is debatable. As we head into the election and beyond, investors might re-evaluate their enthusiasm for India.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.