Published

13th November 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –13th November 2023

Back pedalling central bankers

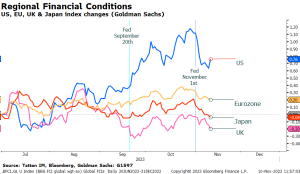

The turnaround rally in stock and bond markets – started by the previous week’s dovish central bank comments – petered out towards the end of last week, with central bankers seemingly at pains to reverse their messaging, or at least reaffirm their continued commitment to keeping interest rates high, however long it takes to get inflation back to their 2% target. Perhaps this was not entirely surprising, given the eight- day streak of US stock market gains and easing bond yields undid much of the financial condition tightening that US Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell referred to recently as doing the central bankers’ job (see chart below – the higher the reading the tighter the financial conditions). But then – not really – or at least the fundamental shift in market sentiment has occurred and is unlikely to flip again so soon.

Indeed, while most of the leading central bank policymakers have sought to say rates will remain restrictive, investors now think the tail risks of higher rates have diminished. Underlying this is the sense that the greatest inflation risk is coming under control, as labour markets appear to be softening.

As has been the case on more than a few occasions in recent years, the UK is doing a good job of exemplifying the global economy’s issues. We discuss the UK’s particular situation in more detail in a separate article.

In fact, sometimes the UK appears to be a caricature of what happens in the rest of the developed world. The pandemic seemed worse, inflation more embedded, growth seemed weaker, and employment has been tighter. Our politicians swing repeatedly between populism, political ideology and pragmatism. The economic data has been more suspect, and the economists have been especially wrong. Now our central bankers are sending more mixed messages than their counterparts.

The current situation may well be because the economy has passed through a turning point. The UK economy has moved into a less inflationary environment. Unfortunately, that goes hand-in-hand with a quickening growth slowdown. We are picking up from our grapevine that small company stress levels appear to have increased, as have job lay-offs.

So, we seem to have passed through the peak in nominal growth (real growth + inflation) and are now heading back down to more normal levels. In most cycles we would expect to see real growth become negative for a time, while inflation starts to undershoot central bank targets. That normally means contraction of economic activity (aka a recession).

What matters for capital markets is the depth and pace of the downswing. Will there be a collapse of both ‘bad’ and ‘good’ borrowers? In this phase, the danger is that contagion problems spread much faster. The increased uncertainty heightens the likelihood that banks, investors and other intermediaries in the financial system, respond to rising risks and uncertainty by pulling their liquidity prematurely. This in itself creates the downswing in both markets and economies (of course, if it happens, no bank or investor would say they were premature).

Central banks actively seek this moment but, for them and us, this is also the point of greatest danger. Information is more than usually uncertain, while the past problems of inflation remain at the forefront of worries. Indeed, because we start from such elevated inflation levels, there is a lot of uncertainty about where we are in this trajectory.

We ask our central banks to constrain inflation and to enable our financial systems to function as optimally as possible. Which of these requirements is most important depends on the situation, but the flip from the first to the second can happen in what feels like the blink of an eye.

Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda said last week that he has an “asymmetric” problem. He can easily raise rates, but cutting them is difficult because in Japan short rates are still around 0%. This is true – as long as growth is on a positive path, the question about raising rates is less catastrophic although, as we know from our experience, perceptions that you have time can lead to complacency.

But we also know the most common central banking mistake is one of delaying rate cuts. Central bankers may be expert enough to see different signals, but they are individuals that are in the public eye and they feel the weight of their responsibilities – currently this is to ease the cost-of-living-crisis pressures inflation has brought upon the public. This can make them cautious, reliant on data that is “authoritative” but is actually too slow-moving to catch the sharp swing from an inflation regime to a recession regime.

Thus, the recent days have been one of hope for investors. Whether it is the Fed, the European Central Bank (ECB) or the Bank of England (BoE), the discussions are acknowledging that rate rises are almost certainly over for now and that cuts are on the cards.

Despite BoE Governor Andrew Bailey saying repeatedly that “it’s too early to talk about rate cuts”, his Chief Economist, Huw Pill, spoke openly to the Chartered Accountant conference about the possibility of rate cuts next year. He must have thought the Governor was asking for conversation to be kept breezy before breakfast. Meanwhile, Jerome Powell undid a bit of his post-meeting dovishness, but markets have sensed a welcome responsiveness.

Financial conditions had tightened after the early autumn meetings, somewhat in Europe, UK and Japan, substantially in the US. As the earlier chart shows, a lot of that tightening has unwound in the past week and, although there has been a small retightening after Powell’s speech, investors are comforted that the risks that policy is stuck have lessened, given they gave back little of the previous eight days’ gains even though they had to – at the same time – grapple with the largest drop in forward earnings expectations for the coming quarter in years.

A fall in energy prices has also helped. We look at gas and electricity markets in the second article this week. For Europe and the UK, a decline in absolute prices is particularly helpful. It is nigh impossible to remove the effective energy surcharge that Russia’s actions have imposed on us, but it is alleviated if energy is reduced in the proportion of overall production costs by making more effective use of it.

Declining commodity and energy costs are usually part of an economic slowdown. This time around, they add monetary policymakers’ ability to be responsive by reducing input inflation pressures.

This week brings the release of provisional inflation data, always an important piece of information, which feels even more important in the current environment. UK consumer prices rises are expected to have fallen back to 4.7% year-on-year, which should allow Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to claim a victory in his inflation pledge (to halve inflation from December 2022’s level of +10.5%). That will be less important than the signal it might send about the chances of rate cuts in the second half of 2024.

Bank of England giving and receiving mixed messages

When the Bank of England (BoE) kept interest rates on hold recently, Governor Andrew Bailey told reporters that it was too early for monetary policymakers to talk about cutting from historically high levels – thanks to persistent inflation pressures and tightness in the UK labour market. Most commentators interpreted his words as adherence to the ‘higher for longer’ mantra gripping central banks on either side of the Atlantic. But last Tuesday, BoE chief economist and fellow Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) member Huw Pill said during a conference’s panel discussion, that market expectations of an interest rate cut next year are not “unreasonable”. Only too early by a few days, perhaps?

Not quite. Governor Bailey reiterated his “too early” verdict since. “The market will of course reach a view”, he said when asked whether bond markets were right to price in cuts, “but we are very clear we are not talking about that. We are saying policy has to be restrictive for an extended period.” Those bond markets had rallied when Pill’s comments came out, but Bailey’s reiteration and implied rebuke undid some of those price gains. Later last Wednesday, yields (the inverse of bond prices) again fell in anticipation of looser monetary policy, touching their lowest level since June.

Markets tend to dislike the uncertainty of mixed messages but rather like the prospect of easier monetary policy. Bailey and Pill are realistically outlining the same view on the economy, but tone can make a world of difference to avid central bank watchers. In fairness to the MPC though, if their policy guidance is confusing, it is probably because the economy they are responding to seems rather fickle. As Bailey, Pill, and the rest of the country are painfully aware, the UK economy is precariously balanced with growth oscillating from slight positive to slight negative, although prices continue to rise. The usual consequence of inflation deriving from stronger economic activity has been broken; inflation has been generated mostly by sustained supply-side pressures, a result of supply-chain-busting factors: demographics, war, pandemic, and Brexit.

The BoE’s message for the better part of two years has been that the labour market is too tight, meaning inflation signals can easily metastasise into the dreaded wage-price spiral. This tightness has apparently continued despite doom and gloom about the economy wherever you look. The unemployment rate has been on a clear uptrend since April, but is still extremely low by historical standards – at 4.3% in the three months to August.

However, the labour market situation is more complicated than it appears. The MPC’s estimates of how jobs might respond to their policies are hampered by the fact that the reliability of the available data is less than ideal for making that call. For the headline unemployment rate published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), this is well known, since it only comes out after a significant delay and so offers at best an indication of how things were five or six months ago.

Accuracy is still a huge problem for the more up-to-date statistics, though. The ONS recently announced it would stop publishing data from its official Labour Force Survey (LFS), citing “increased uncertainty”. The LFS collects responses from households and has long been the main source of ONS data for information on jobs. The problem it faced was essentially a lack of responses, undermining the estimates for wider labour market trends (the US has also seen response rates plunge for some of its labour market surveys).

Even before the pandemic, the proportion of successful interviews had trended downwards. But the pandemic meant a switch from face-to-face interviews to a phone-based survey, which badly affected response rates. The ONS could have reverted to the old survey techniques two years ago, but chose not to do so. Response rates have continued to drop, reaching just 15% in Q2; just 42,500 survey responses to represent an LFS household population of 54 million. Notably, there is particularly low response rates among lowered paid groups, exacerbating concerns about how representative the results are. The ONS plans to resume the LFS next March with new collection methods.

The Monthly Wages and Salaries Survey (MWSS) is another source of shorter-term employment data and is conducted using businesses rather than households and is the source for the average weekly wage data series. This series is due for publication tomorrow, with consumer price inflation on Wednesday, and clearly has not been suspended although it too appears to have suffered from a declining response rate.

There has been a worry for some time that both the LFS and MWSS, the sources of key indicators on wages and hiring practices, might be systematically mis-stating the strength of Britain’s labour market. One reason why this might be the case is selection bias in favour of those with good news, while those lacking time, or cutting back on expenditure (and hence employees), are less likely to respond, if only because of a lack of resources to do so.

In its latest report, instead of the LFS data, the ONS gave data from HMRC. As Oxford Economics points out, the HMRC real-time information (RTI) series is not survey based and data collection has been consistent through the pandemic period. However, this measure has suggested that job growth has been even stronger than the Labour Force Survey recorded. Unfortunately, the RTI has problems too, like the lack of up-to- date information on the self-employed.

Jobs data and wage data have also conflicted with each other. A problem with wage data is that it often reflects backdated wage settlements – like minimum wage rises or increases linked to annually published inflation figures. These rises are essentially lagged effects of previous activity and can make it look like the labour market is running hot when in fact the wage-price mechanism could have already cooled.

An alternative source of employment trend data that economists look at is the seasonally-adjusted trend in job postings on Indeed.com. This job market indicator has been drifting down across most major economies, but the UK has been the laggard through this year and, more recently through October. Oxford Economics see wage growth as cooling – though note it is still too high to meet the BoE’s inflation target.

Other indicators such as the KPMG-REC Report on Jobs and the Manpower Global Employment survey show a cooler wage picture. Allan Monks of JP Morgan Research uses the KPMG-REC salary data as a more forward-looking read on current salary trends:

In an Oxford Economics seminar two weeks ago, past MPC member Michael Saunders said that most of the current MPC members recognise the surveys’ weaknesses, and that seems to be backed by Pill’s comments. If the KPMG-REC salary indicator is right, official wage rise data should move below 3% year-on-year in the early part of 2024, and be soft enough to allow rate cuts.

Official unemployment numbers, while small in absolute terms, have shown a sharp pickup compared to the low and remarkably static rate since 2021. From other economic sources too, we can see that British businesses are in a cost-cutting phase, thanks to persistently high inflation and weak demand. It would be quite incredible if this cost-cutting did not lead to meaningful job losses.

UK year-on-year inflation is still high in both absolute and relative terms, so it makes sense for Bailey to silence any dovish noises, but of course the Governor has had to bear the brunt of the public’s ire over the cost-of-living crisis. No doubt, his speeches will continue to insist that the BoE decisions are dependent on incoming data. The problem is that being dependent on the data from the main official sources means “behind the curve”. We think they will not be so hidebound.

Europe’s natural gas has a bumpy road down

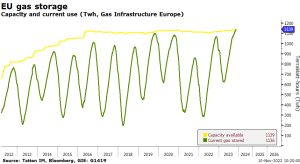

A year ago, Europeans were terrified they would run out of natural gas during a cold and bleak winter. Now, the continent has more gas than it can handle. European gas supplies, which had been building from an already high level (by seasonal standards) since the spring, officially reached 100% of storage recently. The 100% level refers to the secured capacity of working gas volume as reported by individual facilities which, in many cases, can be lower than the total physical capacity. That means reported storage can sometimes exceed 100%, as was the case in Portugal (107.3%), Romania (103%), Spain (100.4%) and Germany (100.03%) as of the start of last week.

Germany, one of the most at risk from Russia’s turning off the taps last year, set itself strict storage targets in the summer of 2022. This is why storage levels in the Europe’s largest economy also hit 100% in November 2022, despite painfully high energy prices at the time. This year’s surplus is definitely less defensive. This autumn has seen German storage facilities meeting every capacity-building target substantially ahead of schedule.

The same is true for the European Union (EU) at large, with chambers above target and ahead of schedule compared to Brussels’ directives, according to Gas Infrastructure Europe. This is a far cry from the fears of last year when Russia’s war in Ukraine decimated Europe’s energy supplies and policymakers planned for rolling blackouts. In a turn of cosmic irony, European energy companies are now reportedly storing excess gas in Ukraine – the country’s reserves now at their highest since the invasion.

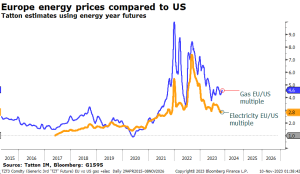

The supply balance has led to a period of relative stability for European energy. Gas price spikes in the wake of war – and Moscow’s subsequent withholding of supply – were excruciating, and meant that European and British energy (both of which are heavily reliant on natural gas) prices were several orders of magnitude higher than in the US. This year, futures pricing for Dutch TTF (Europe’s benchmark for natural gas) has been much more stable, staying within a consistent range, albeit a wide one.

Policy choices obviously played a big part. The biggest European energy shock in relative price increase terms since the Second World War necessitated a rethink. The immediate priority was finding other short- term sources, exemplified by the massive increase in imports of liquified natural gas (LNG), but structural changes for the medium and long term have been aggressively pursued too. Strict storage build targets are part of it, but these were helped by moves to limit household and business energy consumption – particularly in Germany – though this was in part thanks to an unusually mild winter last year. Less remarked on has been the increase in storage capacity itself, although this has been a slow process that has not yet had a massive impact at the aggregate supply level.

The biggest structural push, over the longer term at least, is to ween Europe off natural gas altogether. We have written before that extraordinary events over the last few years have led to competing priorities for national governments. The visibly devastating effects of climate change push politics in favour of a global green transition, but the intense and repeated supply-side crises (some of which have been because of climate change) have made supply-chain security – and above all else, energy security – top of the agenda.

How much these priorities push against each other differs by region. The US, with its abundant supplies of fossil fuels, is more focused on drilling, while Europe has tried to increase renewables’ share of its energy mix. But even if the EU’s long-term energy security and environmental ambitions both point towards renewables, politicians are well aware that gas will be needed for the foreseeable future. Pipelines to alternative suppliers are being built, and there has been a marked increase in LNG inflows.

Recognition of this need is perhaps why wholesale gas prices have not fallen further. Supplies were above 60% of capacity at the start of spring – the seasonal low point for reserves – and the build has been ahead of schedule ever since, but European gas and energy prices are still high by historical levels. This is despite weak demand on the continent, both current and projected.

Analysts at JP Morgan have pointed out that, even assuming Europe’s green transition goes ahead unimpeded, natural gas will be needed long into the future, as it is by far the easiest source of meeting short-term mismatches between energy supply and demand. This role as a backstop is likely to mean a slow unwinding of demand, and hence no great need for new gas production. Their medium and long-term outlook for European and global gas prices therefore points downwards.

The way down is likely to be bumpy, however. Even with abundant supplies, the technologies for transporting or using them are not very flexible. This is fine if we can plan for periods of supply-demand imbalance, but the last few years have shown that the best laid plans go awry. For example, even with gas supplies filling up all available tanks, Europe is estimated to have at most two months of required gas for the winter. Two months spare should be more than enough, but further complications could always come about. The brittle nature of energy markets means that prices will likely remain volatility, even if the general trend is downward.

Still, a slow downward path will be good for European businesses and households. But unfortunately, this improvement in absolute terms is unlikely to give much benefit in relative terms. For one thing, the current oversupply is largely down to weak economic demand – hardly a good sign for the near future.

Moreover, the gap between US and European energy prices is big and the multiple is structural. By our calculation, before the pandemic, the cost of shipping LNG was twice that of pipelines. The investment needed to increase LNG port and storage capacity has been substantial and adds further to the cost in the medium term.

As the chart above shows, gas prices have fallen but Europe’s prices remain over four times those of the US. Electricity prices remain over twice as expensive.

Of course, there is room for energy company margins to compress back to previous levels. They have definitely been a beneficiary. For example, the LNG shipper Cheniere has seen its expected net income margins go from the pre-pandemic average of 8% to above 15%.

The European economy is well behind the US. Without a near-term resolution of the war in Ukraine, it will take some years for the structural impediments to be overcome by investment. It is more likely that it will take a significant shift downwards in absolute energy prices to make Europe competitive again. Lower energy prices certainly cannot hurt.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.