Published

12th August 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 12th August 2024

Market correction turns into pothole

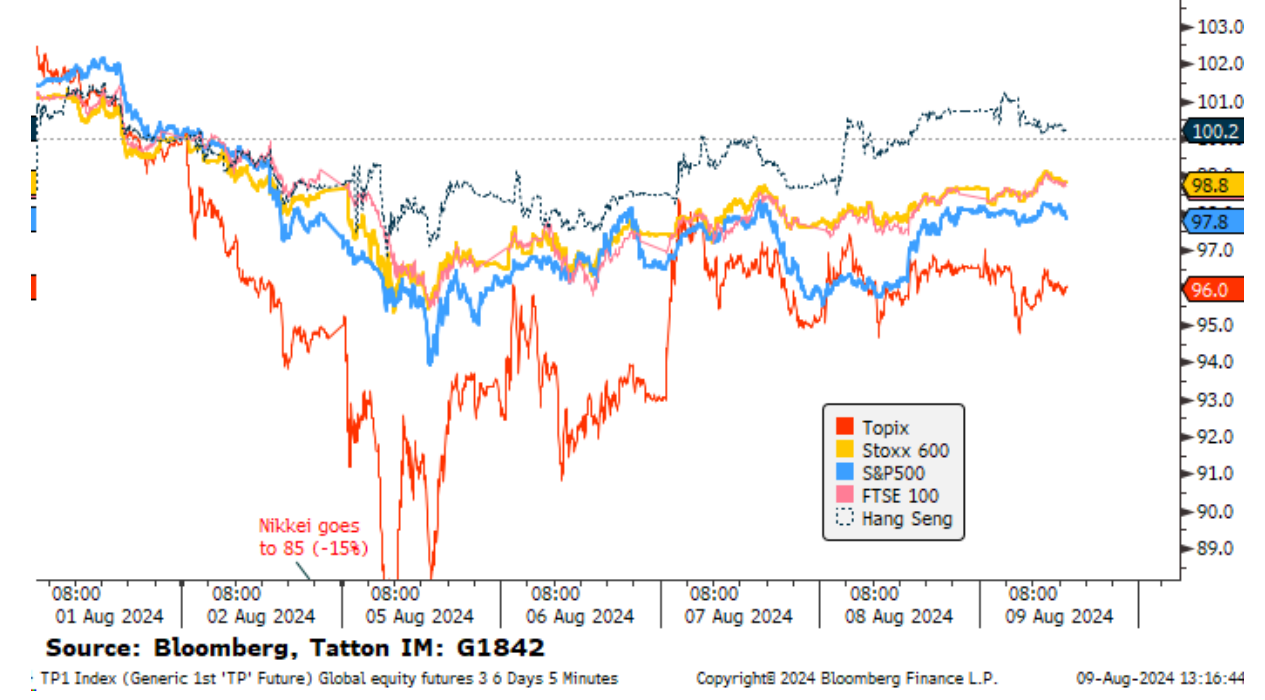

Our sign-off last week was cautiously optimistic – predicting a bumpy ride to a decent destination in markets. Cue the worst daily loss for the S&P 500 in nearly two years at the beginning of last week after a terrible session in Japan, and sharp losses for most other major indices. US recession fears – stoked by a distinctly disappointing jobs report the previous Friday – formed the backdrop for the sell-off, however, market liquidity concerns emanating from Japan’s actions were the spark.

But then global stocks staged a promising recovery for the rest of last week, and the S&P had its biggest daily gain since late 2022 on Thursday. A bumpy ride indeed. The jury is still out on the destination.

After exceptionally low volatility in 2024, the VIX index, which measures expected swings in US stocks, spiked into last Monday. Recession signals clearly played a role, but the immediate story was about market liquidity. The Bank of Japan raising rates from ultra-low levels hurt the ‘carry trade’ (borrowing where rates are low and putting the money into risk assets elsewhere) which has been a source of funding for hedge funds this year. The drying up of liquidity made trading more volatile and, when volatility metrics increase, hedge funds’ risk protocols often require them to dial down their investment positions. We cover the Japan story in a separate article.

This went hand in hand with a reduction in US liquidity. The Federal Reserve is still taking money out of the system through quantitative tightening, despite its recent dovish signals. Meanwhile, the large pots of cash that households received during the pandemic (which could not be spent immediately and so were saved) have been declining. Indeed, as a whole, the US appears to have stopped taking out of the cash pots since the early summer. Nevertheless, the reduced cash savings may have been part of a liquidity shortage which, recently, was suddenly revealed to markets. Investors’ perception of risks grew, and we had one of the steepest increases in volatility we have seen. This was across most regions and almost all asset classes, from commodities and cryptocurrencies to equities and bonds (albeit bonds were volatile to the upside).

Interestingly, we suspect that the growth of day trading instruments like so-called zero-day options and high-frequency trading have contributed to the substantial swings in implied volatility (as measured by the Vix, rather than just recent historical swings). The timelines between trades have been shortened, and volatility is always measured as movement within a certain time-frame. So, higher frequency trades can exacerbate spikes in volatility, which in turn increase markets’ reactiveness.

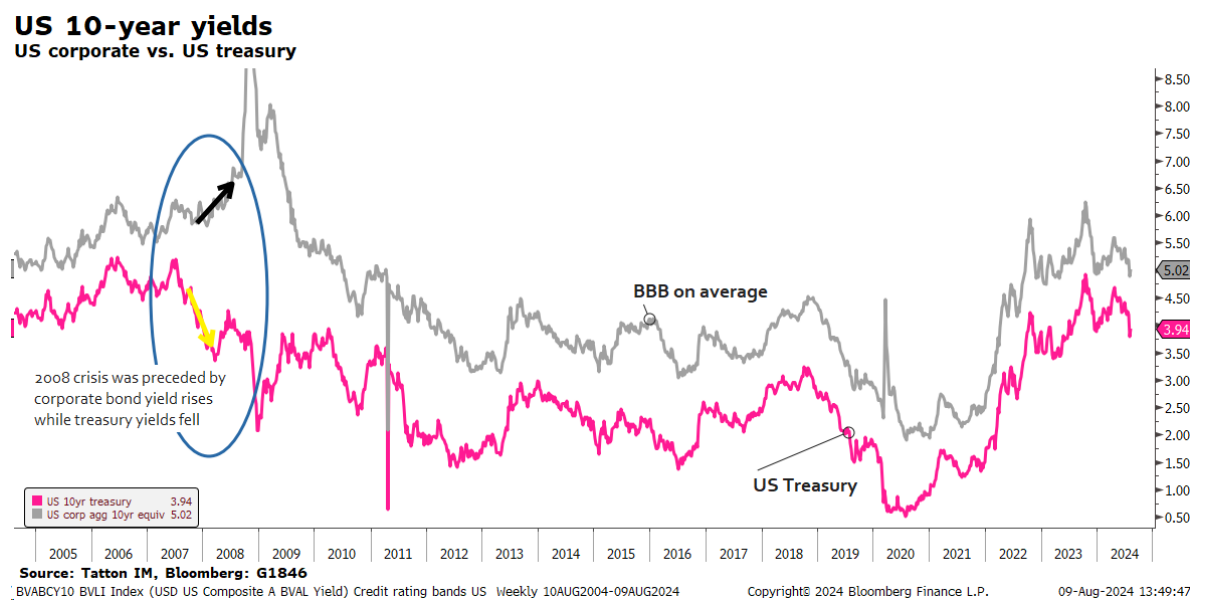

But recession still not likely

We say almost all asset classes were highly volatile, because there is one notable exception. Corporate credit spreads – the difference between corporate and government bond yields – increased early last week but, in fact, corporate bond yields have fallen in aggregate (and so prices have gained) from the previous week, thanks to the sharp fall in the ‘risk free’ rate of government bond yields. Credit stress is one of the hallmarks of recession, so the fact corporate credit has behaved well tells us that recession fears might be overblown.

Economists at JPMorgan made a stir last week by suggesting there was around a 35%-50% chance of US recession by the end of 2024, and undoubtedly a near-term contraction is a higher risk now than a few months ago. But it remains unlikely, and the base case is still a ‘soft landing’ (growth slows enough to lower rates, but not enough to trigger recession).

Survey data from US manufacturers, particularly on employment expectations, was one of the factors behind recent market pessimism. But survey data from the much larger services sector continues to be strong. The situation will only be helped by the Fed’s all-but-certain rate cut in September.

A decent enough outlook

Markets were spooked early last week, but there is a fair amount to be positive about. Global recession is still unlikely, and rate cuts will offer relief. Moreover, the knock to growth expectations has translated into a steep fallback in yields.

These should provide some support for equity valuations, and also economic activity. US housebuilding, for example, will benefit from lower mortgage rates – and could release a lot of bottled-up activity.

Now that US long bond yields have turned lower, there is a good chance of a substantial fall in mortgage rates. Mortgage holders have begun to refinance old mortgages more often, as last week’s “refi” data showed. Outright mortgage rates have fallen to 6.6% but could drop to 6% in the next few months, even if longer-term treasury yields remain around 4%, because the 30-year average spread is 1.4%.

But not out of the woods yet

This feels like a market shakeout that has been brewing for a few weeks. Goldman Sachs pointed out last week that risk signals – of the kind that feed into the models used by many hedge funds – had been rising since June. Essentially, their models look for signals of herding behaviour. Some hedge funds had therefore been reducing their exposure to risk assets ahead of the sell-off and so had room to buy back into equity markets, as others were being shaken out.

Thus, we have seen a reasonably quick settling back down in actual volatility and in expected volatility implied by options trading. After sharp falls, equity prices tend to swing up and down for a while, and those swings get smaller, like a pendulum coming to an eventual stop. Last week has seen a quicker than usual dampening, suggesting that fears of financial instability have dissipated rapidly.

However, we think we are also in a different phase for the equity markets’ medium-term outlooks. Valuations based on recent earnings are lower but not cheap; they still carry optimism about earnings growth. The fall back in yields helps support the valuations, but should also reduce the likely average path for earnings growth. Maybe we end up with somewhat higher valuations but with future earnings lower than previously expected. That leaves us with positive but (slightly) lower expected returns, and perhaps with a different set of likely winners.

It has been a long time since the Bank of Japan (BoJ) received this much global media attention. The bank has raised rates twice this year after nearly a decade of stasis – and its most recent hike set off the worst day for Japanese stock traders since 1987. Its policy stance has had a huge impact on western markets too: near-zero rates weakened the yen and provided a cheap source of funding for leveraged investors for most of 2024. Rising Japanese rates (and falling US rates) together with a strengthening of the Yen, have now reversed those trends and drained that funding. Journalists have called it the ‘carry-trade unwind’ and it is one of the reasons behind US stock market troubles in recent weeks.

TOPIX loses its hard-earned gains

Japanese stocks have had a horrible week. The benchmark TOPIX lost 12.2% last Monday, making it the weakest global performer in sterling terms – despite a massive leg up in the yen’s value. Prior to last week, Japan had been one of the best performing regions in the world this year (up 11.6% year-to-date in sterling terms as of 31 July), but losses since have been enough to undo all of 2024’s gains.

The TOPIX regained a lot of that ground last Tuesday and Wednesday, but this volatility is not good for investor confidence. Risk appetite among Japanese investors is historically slow to build and quick to collapse. There is not much economic optimism to fall back on either. Japanese growth has been virtually zero this year – despite what stock market gains might lead you to believe – and consumption has been knocked by inflation. (Japanese inflation has been much lower than in the West, but Japanese households are used to decades of near-zero price growth)

It took the BoJ a long time to turn ‘hawkish’ (if you can call 0.25% rates that) given Japan’s historic stagnation. And policymakers have already had to tone down the rate-hike talk, with the deputy governor announcing last Wednesday that “it is necessary to maintain current levels of monetary easing for the time being”. These dovish tones bolstered the stock rebound.

BoJ the hedge fund funder?

The BoJ will be wary of staying too easy, though. For decades, Japanese borrowing has been fairly tame despite extremely accommodative monetary policy. But international players have been much more willing to take advantage, it seems. The chasm between Japanese rates and those elsewhere (particularly the US and Mexico) has pushed so much capital into the ‘carry trade’ in recent years – borrowing where it is cheap and keeping the money in higher-yielding assets.

The carry trade is very attractive to short-term speculative investors like hedge funds. The huge slide in the yen for most of this year amplified this: the rate gap increased bets on a cheaper yen and, as it fell, hedge funds could put more into high-yielding assets like US equity. Needless to say, international hedge funds are not who the BoJ intends to support. It is possible that policymakers saw the relatively limited impact its rates and bond buying was having on the domestic economy – compared to the large impact it was having on the yen – and thereby decided to become more hawkish.

The shakeout of the yen carry trade partly explains the tech sell-off in the US. The trade has previously been a source of funding for hedge funds, who for much of this year were ‘long’ on the tech mega-caps, and ‘short’ other assets like US small-cap. With the BoJ tightening and the US Federal Reserve set to cut rates, expected returns from the carry trade are lower – hence the yen rose, and volatility ensued. Higher volatility forces hedge funds to reduce their risk exposures, which meant reducing their short-yen and longtech positions.

The shakeout could do Japan some good

As noted above, this volatility will scare Japanese domestic investors too. But the long-term case for Japanese equity is not undermined by recent moves. The reason Japanese stocks climbed to new all-time highs earlier this year (breaking a 35-year hoodoo) is that prospects for corporate earnings improved. Reforms to corporate structures – in particular, those making companies more amenable to foreign ownership or influence – were a huge benefit, while Japan high-grade exports are well positioned to benefit from a rebound in global demand.

Thanks to the consistent slide in the yen, Japanese labour has been extremely cheap – in terms of productivity compared to unit labour costs – for some time. Japanese exporters can therefore be extremely competitive and, thanks to recent governance reforms, that competitiveness can translate into profit. Honda’s strong corporate earnings results for Q2, announced last Wednesday, are testament to this.

Even with the yen’s recent gains, there is a very long way to go before Japanese goods and services would stop being cheap (let alone start to look expensive) relative to the US. The BoJ is a structurally dovish central bank too – even if it is currently on a tightening cycle – which puts a limit on how strong the yen can go. The ingredients are all there for profit growth over the long-term. If that comes through, Japanese stocks will start to look very cheap. Hopefully, the carry-trade shakeout is a much needed catharsis.

Interest rate expectations

Opinions vary on how central banks should steer through capital market turbulence. Global investors, spooked by a weaker-than-expected US jobs report and a potential recession, were in a panic recently. Government bond yields dropped sharply in response – reflecting an expectation that central bankers will cut interest rates more rapidly and more sharply than previously indicated. But some renowned economists, including Mohamed El-Arian and Barry Eichengreen, argue monetary policymakers should hold their nerve – sticking to the plan, even if it upsets markets in the short-term.

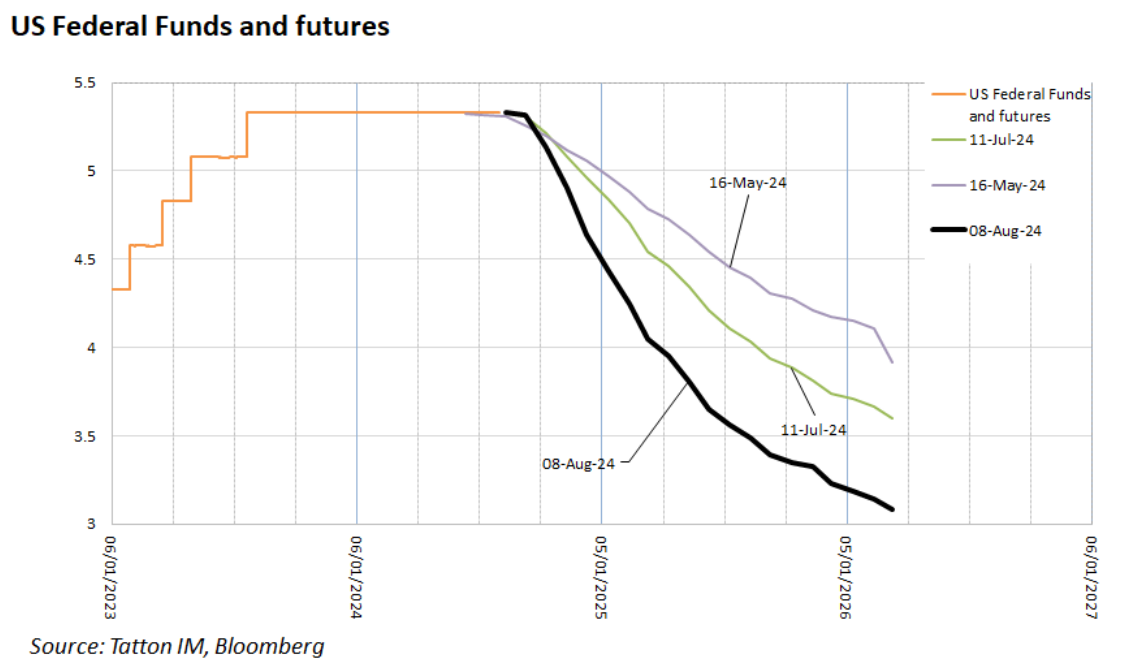

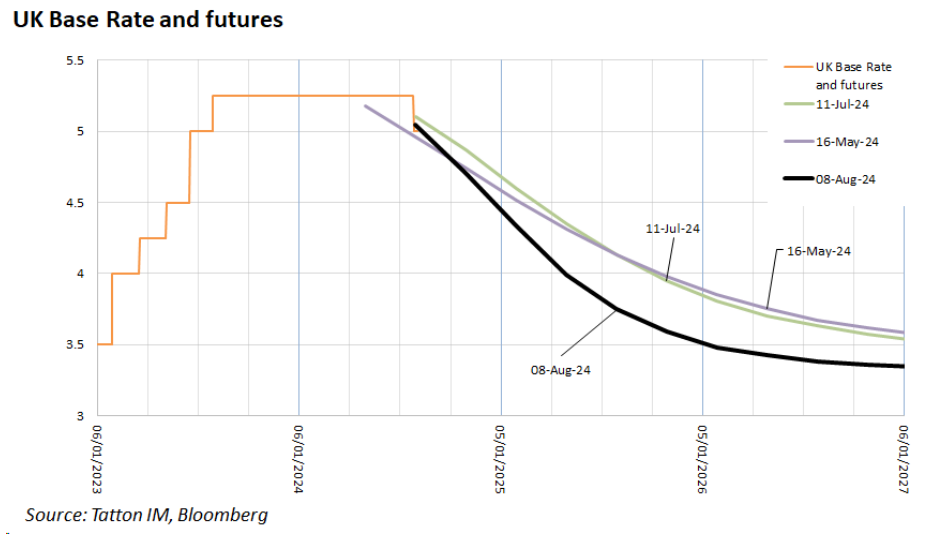

Interest rate expectations have moved down heavily across the board compared to a month ago. It is a shame (or perhaps a blessing, for central bankers) that this happened immediately after a slew of consequential meetings. The Federal Reserve (Fed), Bank of England (BoE) and Bank of Japan (BoJ) all met recently, meaning it could be some time before we get another clear update on their plans. We will try to discern them from what signals there are in the meantime.

US Federal Reserve

A September rate cut from the Fed has been on the cards for some time, thanks to clear signals of a slowing US economy. Several major recent data releases were weaker-than-expected, particularly with regards to the labour market, leading some to increased bets that the Fed was going to cut. That did not happen, but Chairman Jerome Powell sounded so dovish in his post-meeting press conference that it was unclear why not.

The recent labour market report showed the US added significantly fewer jobs than analysts expected. More importantly, the unemployment rate for July came in at 4.3%, triggering the ‘Sahm Rule’ recession indicator (when three-month average unemployment is more than 0.5% above the low point of the past 12 months). Historically, unemployment spikes of this size tend to spiral, as job losses weigh on demand, which create further job losses.

As the chart above shows, markets’ implied rate expectations have moved significantly lower. The Fed is currently holding rates between 5.25-5.5%, but investors expect rates to be at 4.5% by January. There are suggestions that the Fed could cut before its scheduled September meeting as an emergency measure – as it did at the start of the pandemic – or instead, cut by 0.5 percentage points in the autumn.

Either of those would be extreme measures, but they would be required for the Fed to meet market expectations. Something has to give: either the Fed does the extraordinary or bond markets will be proven wrong and have to adjust. Given recent history, we suspect the latter is more likely. The US economy is slowing, but recession fears are arguably overdone – and Powell has shown a willingness to stick to the plan even when markets do not like it.

Bank of England

The BoE cut rates for the first time since 2020, but governor Andrew Bailey stressed that further cuts are not a given anytime soon. Like everywhere else, though, turmoil since has shifted markets’ implied rate expectations. Bond markets think that UK rates will be 0.5% lower by the start of next year. BoE rate expectations have not come down as sharply as elsewhere, though. Markets think that the bank will settle on 3.5% at some point in 2026, compared to mid-2025 for the US, and before the end of 2024 in Europe.

There are cyclical and structural reasons for this. UK economic data has actually been improving lately, counter to the trend in most developed countries. We are coming off a long streak of weak activity and high inflation – worse than developed world peers – but inflation has been at the BoE’s 2% target for two consecutive months and that is clearly helping confidence. The most recent set of business sentiment surveys were stronger in the UK than anywhere else, suggesting that we might not need as much support as elsewhere.

Even if Britain’s economy did need that support, the BoE would be less likely to give it than peers. While the 2% inflation target is common across the world, the BoE is one of the only central banks to have a target set externally with rules of enforcement (Bailey has to write to the Chancellor when inflation is 1% either side of target). There has been a lot of discussion this year about whether a higher target (or no official target) would be appropriate in the post-pandemic world – and some signs that the Fed and ECB have already implicitly shifted. The BoE cannot change target on its own, though, which arguably makes it structurally more hawkish.

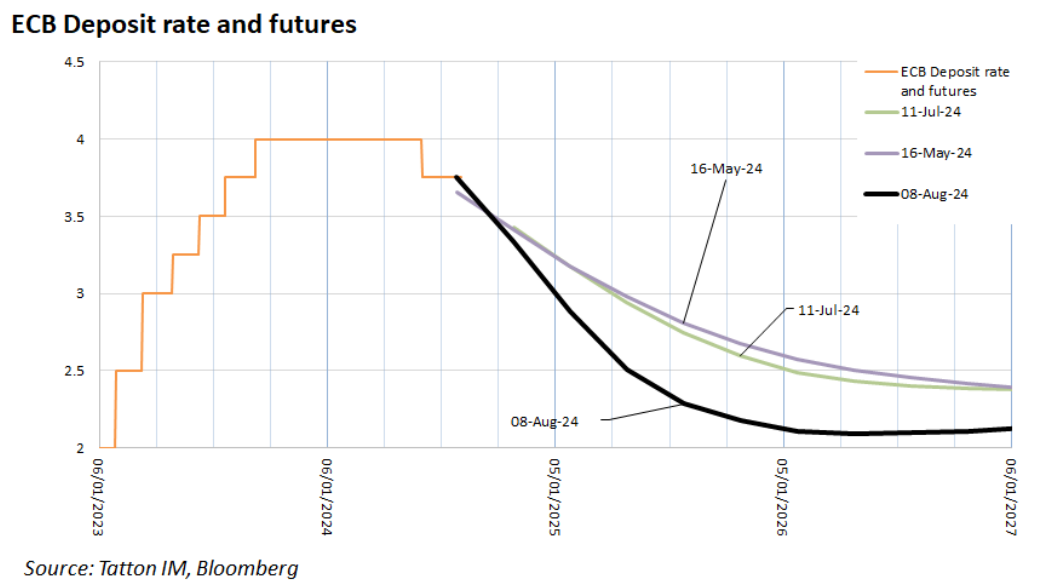

European Central Bank The ECB cut rates in June, and bond markets expect it to do so again in September. That expectation is more or less the same as a few weeks ago, but the path out from there has moved sharply lower. Markets now expect a sharp decline, hitting 3% at the start of next year and settling closer to 2% by the end of 2025. That steep decline is in spite of the fact that Eurozone inflation edged up to 2.6% in July – above analyst predictions.

Slightly stronger growth and inflation numbers are unlikely to stop the ECB from loosening, though, considering the dire state of forward-looking indicators like business sentiment surveys. The Eurozone still finds itself in the middle of a weakening global economy, oversupply from China and geopolitical tensions. If the ECB cuts in line with market expectations, it would mean a rate-lowering cycle almost as aggressive as the pace of hiking before. Europe’s ailing economy might need it all the same.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.