Published

11th December 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 1th December 2023

A bit of a downer

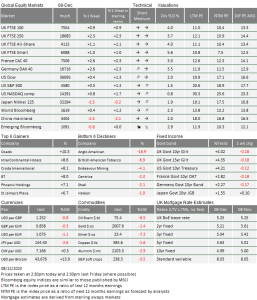

We review November’s cheery asset performance below. Early December is also currently on a positive track and trading volumes have been higher than November’s averages generally, suggesting quite a bit of capital is being put to work by investors.

Global bond yields have fallen yet again (meaning bond prices have risen). This has been driven by a round of some indications of weaker employment data in the US, and soft (but not awful) purchasing manager survey indices, combined with dovish noises especially from members of the European Central Bank (ECB).

The US employment report surprised economists by showing a reasonable level of job creation and a very surprising fall in the unemployment rate. Rate expectations have fallen because the policy setters at the US Federal Reserve (Fed) appear be more focused on inflation declines than worrying about what level of unemployment is too low for comfort. However, bond investors had expected the US unemployment rate to worsen to 4% at least, and November’s data does not allow for any rate cuts without some other factor impinging. Equities saw some softness (especially in the raw materials and energy areas which we discuss below). However, the US ‘Magnificent Seven’ had a good bounce after enduring some fears about their exposure to softer consumer demand.

Over the course of the past week, there was some notice taken of a rise in the “Secured Overnight Financing Rate”, a well-used interbank market. In truth, the move was small, but participants are sensitised to such arcane indicators, particularly around the turn of the year. Holidays and book-closings can make things difficult for more stressed institutions.

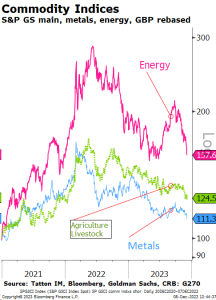

While US bonds ended the week unchanged from last week, European and UK bonds have done well, as our performance table (always to be found at the end of the full copy) shows. The softness in global growth is being signalled in both economic data and in commodity market prices. Last week, we talked of how OPEC+ had shown its relative lack of cohesion and how that inability to act together has led to ineffective supply cuts. We said then that demand need not necessarily be weak in order for prices to fall.

However, during last week we have seen more oil price falls, continuing the pace of the previous week. In addition, global industrial metals and agricultural prices have moved down as the chart on the left shows. They are less volatile than energy prices (mainly because energy stores are always relatively low compared to ongoing use), so the lesser decline is still significant.

As COP28 came to a close over the weekend, the deliberations have been neither a help nor a hindrance to asset and commodity prices, nor perhaps should they be. COP28 president (and oil executive) Sultan Al Jaber took the opportunity to swing the debate towards responsible fossil fuel policies. Each of these meetings became more embroiled in detail and ran the risk of losing any momentum for meaningful change. Still, ultimately, progress on dealing with emissions will be in the enactment of detailed policy, so perhaps this is good news.

The conference also turned its attention to the loss of the natural world, which many will think is a good refocusing.

Commodity prices are still a higher than they were 2021, but the decline from mid-2022 is clear. In the past 15 years, the biggest demand swing has emanated from China, and there are all sorts of signals that the world’s second-largest economy is not providing the growth leadership that the largest economy in the world has given us. Chinese economic data don’t appear so bad, and GDP estimates from JP Morgan are running at about a 6% annualised rate. Yet equity prices fell again over at the start of the month, which doesn’t align with signals coming from markets.

Last week, China’s Politburo met and affirmed a significant fiscal push next year (we write on China’s situation below). There is also an exception to the commodity signal; domestic iron and steel prices are picking up when usually they would face seasonal downward pressure because of year-end inventory run- offs.

Among the policies being swung into action, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has introduced something that looks very much like quantitative easing (QE), or the buying of bonds. This policy can work in different ways but one of its possible implications is that financial market liquidity improves, which can then feed through into rises in risk asset prices.

The lack of foreign equity buyers has generated much comment, but the similar lack of domestic equity buyers has also been notable. Probably, therefore, the first indication of a turn in sentiment will come from the equity market itself, and then the dynamic could be quite strong.

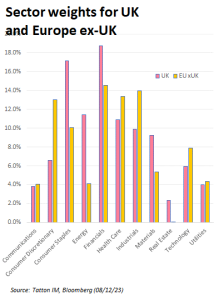

Energy and materials equity and credit sectors have been understandably poor performers in recent days. By market capitalisation, the UK has more than 20% in the combined sectors, while Europe has less than 10%. The predominance of such companies in the UK stock market has sent the FTSE 100 to the back of the class in global terms.

We still have a slightly bigger weighting in financials, and the sector has done quite well amid declining financial pressures. However, UK financials are up about 2% this week, while materials and energy are down almost 2.5%.

Europe is also doing well courtesy of a bounce in luxury goods, which may be a signal of China confidence returning. These stocks were strong performers in the post-lockdown bounce earlier this year.

Both the Nationwide and Halifax (now Lloyds Bank/S&P Global) house price indices have shown a small rise in prices. This week we will get the Rightmove and Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors reports. The fall- back in rate expectations has helped mortgage demand pick up a little, and it will be interesting to see whether this improves the estate agents’ mood.

Next week will be our last full weekly of the year when we will also present our brief outlook for 2024.

November review

What a difference a few weeks make. In a complete turnaround from October, November was all smiles for international investors. Capital market returns were positive across virtually all regions, and in many cases massively so. As autumn ended, fears over prolonged inflation and interest rates staying higher for longer seemed to dwindle with the daylight. A perceived softening from central banks preceded a significant rally in global bond prices. The sinking of bond yields – the inverse of prices – lowered the so-called ‘risk- free’ rate of return, and made stocks look much more attractive by comparison. The table below shows November’s returns across key regions and asset classes.

| Asset Class | Index | November | 3 Months | 6

months |

YTD | 12

months |

| UK Large Cap | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 2.4 | |

| UK Ethical Large Cap | 1.4 | –0.3 | –2.1 | –0.2 | –1.5 | |

| Europe ex-UK | 6.2 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 10.0 | 9.0 | |

|

Equities |

US Large Cap | 4.6 | 1.8 | 7.9 | 14.8 | 7.1 |

| US Technology Large Cap | 6.2 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 30.2 | 17.7 | |

| Japan | 4.1 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 9.5 | 8.7 | |

| Global Stocks | 4.7 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 10.8 | 5.4 | |

| Emerging Markets | 3.5 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0.4 | –2.0 | |

| UK Gilts All Stocks | 2.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 | –1.6 | –5.7 | |

| Bonds | £-Sterling Corporate Bond Index | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 3.1 |

| Global Aggregate Bond Index | 3.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 1.6 | |

| Commodity Index | –7.6 | –3.8 | 9.4 | –5.9 | –8.1 | |

| Commodities | Brent Crude Oil Price | –8.8 | –6.8 | 9.0 | –10.6 | –12.5 |

| Spot Gold Price | –2.2 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 6.8 | 8.6 | |

| Inflation | UK Consumer Price Index (% Chg for period)* | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 4.2 |

| Cash rates | SONIA 3-Month | 0.4 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| Property | Global REITs | 6.0 | –1.4 | –0.5 | –5.2 | –8.6 |

Nowhere were the changing tides more keenly felt than Europe, whose benchmark stock index gained a mightily impressive 6.2% through the month in sterling terms. Even better for Europeans was the news that consumer price inflation for the Eurozone fell to 2.4% year-on-year in November, down from 2.9% in October and the lowest reading since July 2021. The continent has been hit the hardest by energy price spikes over the last two years, but that sensitivity is now coming good as energy prices continue to fall.

Falling input costs – exemplified by November’s 7.6% fall in commodity prices – put pressure on the European Central Bank (ECB) to relax its monetary policy, but Governor Christine Lagarde has been steadfast in her commitment to the ‘higher for longer’ mantra. Markets are convinced she will relent, though, with many bond traders now betting on a European rate cut as soon as Q2 next year. Implied market expectations put rates nearly 1.5 percentage points lower than the current 4% level by the end of 2024. The ECB will meet this week, and policymakers are expected to downgrade Europe’s growth outlook after much worse than expected data from Germany. Lagarde’s resolve will be sorely tested.

A big part of investor positivity towards Europe has been because European assets are so sensitive to expectations for the global economic cycle – which some may believe could be turning thanks to lower inflation and expected monetary easing. Small- and mid-cap businesses – much more sensitive to economic and financial conditions – did well in November. Emerging Markets (EM), which so often rise and fall with the global economic tides, also did well after what has been a challenging year. Incredibly, EM equities are now up year-to-date in sterling terms.

The only exception for EMs, and indeed for major asset markets in general, was China. Chinese equities endured yet another down month, for reasons we cover in a separate article, but two things are worth noting here. First, even with EMs’ largest component suffering a setback, the headline EM index is up on a monthly, quarterly and year-to-date basis, showing the wider resilience of EMs. Second, and perhaps more importantly, economic weakness in China is acting as a deflationary force for the rest of the world, as the country ships out exports at lower prices. This is a serious benefit at the moment, allowing central bankers room to loosen policies.

The bond market rally was the biggest factor underlying equity growth, at least in the first half of November. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) left rates unchanged at its November meeting, but the weakness of US and global inflation data since then has convinced markets that even the Fed – overseeing by far the strongest internal economy in the developed world – will look to cut rates by mid-2024. Bond yields fell and equity valuations adjusted, pushing up rate-sensitive assets in particular. This can be seen in the stellar performance of large US tech companies.

From mid-month, though, the mood seemed to shift. Markets were still positive, but now dared to envisage not only lower interest rates, but stronger growth too. That meant outperformance for near-term growth assets like small-cap companies, which began outperforming the US mega-caps. Underlying all of this was the belief that the proverbial ‘soft landing’ – a turning of the economic cycle without any substantial downturn – could actually be within reach.

This is because, despite all the doom and gloom this year over extremely challenging financial and economic conditions, at no point have we seen signs of systemic credit stress. The banking crisis in March was managed thanks to Fed liquidity and deposit guarantees. Now, monetary policy is shifting, and a high level of defaults have still not come. This has allowed credit spreads (the difference between corporate and government borrowing rates) to fall significantly, increasing hopes of growth next year.

Where growth expectations have not come through, unfortunately, is in the UK. UK bond yields led the way down earlier in the month, but shifting economic expectations did not follow through, perhaps explaining the UK Large-Cap index’s relatively mild 2.3% return. The situation was not helped by Britain’s policymakers, who together suggested ‘higher for longer’ might be even stronger in the UK than elsewhere. The Bank of England (BoE) continues to shout down any suggestion that rates can be cut next year – though we have our doubts about its resolve, as noted last week.

The BoE is perhaps put in a bind by the Treasury though, after Chancellor Jeremy Hunt used his Autumn Statement to signal some mild tax giveaways. While these are unlikely to substantially increase growth, they do eat into the fiscal headroom that had previously bolstered government finances. With that headroom gone, there is a continued feeling that UK inflation – and hence, higher interest rates – are not over. UK bonds and subsequently equities fell behind their peers.

Overall, rainy November was much less bleak than had been feared. No-news days at the two biggest central banks – the Fed and the ECB – was welcomed with open arms. For the global economy, perhaps the most important factor heading into the year-end is that the US dollar ceased rising. Having been strengthening for so long, a somehow softer dollar gives the cyclical recovery more space, and those borrowing in USD (predominantly EMs) room to breathe.

Xi goes to America

During last month’s rally in global stock prices, only one major economy did not partake in the spoils: China. Both of China’s benchmark stock indices – the CSI 300 and the Hang Seng – are down by more than 6% over the last month in local currency terms. It was the continuation of a miserable year in Chinese markets, where economic and policy disappointments have been the defining feature. At the time of writing, the CSI is down 12.5% year-to-date in renminbi terms, while the Hang Seng has dropped a painful 18.3%.

Weaker-than-expected growth and trade – compared to admittedly high expectations – has been the root of China’s issues for some time. The government has repeatedly tried to counteract this with various support schemes or political pronouncements – to varying degrees of success. Last week brought another headache for Beijing to deal with, after ratings agency Moody’s cut China’s credit outlook to negative. Moody’s pessimism extends to both government and private banking debt – both of which it suggests are feeling the pressure from an extended property market downturn.

We should point out that Moody’s has only changed its outlook on Chinese credit, but Beijing’s A1 rating remains, and in fact was reaffirmed in Moody’s statement. This has been the case since a downgrade from A3 in 2017, and current bearishness will not necessarily change that. Even if it does, an A1 rating for a nominally ‘emerging’ market with relatively small financial linkages to western investors (compared to the huge economic linkages, that is) is pretty good. A slight downgrade is unlikely to affect China’s medium- term borrowing capacity in a big way.

That said, the news is clearly not a good thing for the Communist Party government. The more China’s economy has disappointed this year, the greater the priority of arresting the decline has become – evidenced by the huge monetary and fiscal supports announced in November. And financial stress has been worsened by the exodus of foreign investors from Chinese markets this year. Beijing needs to shore up creditworthiness at all levels. Tellingly, the Chinese Finance Ministry’s response to Moody’s announcement was less spiky than we have come to expect over the last few years, saying only that it was “disappointed” in the decision, and that it “is unnecessary for Moody’s to worry about China’s growth prospects and fiscal sustainability”.

The reason Moody’s disagrees – and why so many investors are bearish on China – is its severely stressed property sector. Property developers have been in a perpetual liquidity crisis since Evergrande’s slow- motion collapse started more than two years ago. Beijing has long been reluctant to step in – not wanting to inflate the credit bubble that put the economy in this position – but recent developments have forced its hand. Default fears at Country Garden Holdings recently led to the government putting the property giant on a list of those eligible for financial support, not wanting liquidity issues to spillover.

The need to prop up the economy is what makes Moody’s worried about Beijing’s finances, but indirect support is arguably a bigger problem than direct handouts. China’s fiscal model puts local governments largely in charge of their own development financing, which for years they have done through property sales instead of direct taxes. This model relies on high property prices, giving developers more money to buy land. Crises in the property sector have therefore decimated local government finances, with local governments then relying on Beijing to bail them out.

The problem is not too dissimilar to one we see in the UK – which also raised fiscal concerns – but significantly bigger, as China does a huge amount of its spending through local bodies. By most standard tax, spending and borrowing metrics, the central government is in good fiscal health – evidenced by the 2.7% nominal yield on its 10-year bond, significantly lower than yields in the US and UK. But the concern is that Beijing will suddenly get an unpayable bill and have to borrow massively. These problems are hampered by the general sluggishness of China’s domestic economy, made much worse by recent export trends.

Consumers are feeling pessimistic, and for good reason: 8.5 million of them (around 1% of the total working- age population) have defaulted on debt payments since the start of the pandemic, and been blacklisted by authorities. As well as severely constraining China’s domestic demand – a side of the economy Beijing avowedly wants to foster – struggling consumers cannot pay taxes, hence reducing the government’s funds and worsening its fiscal metrics.

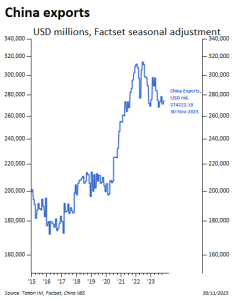

Trade has been at the heart of manufacturers’ woes. A push towards climate-friendly products has faced a backlash from western consumers and businesses in the past year, especially in relation to Chinese electric vehicle products. Last week’s release of data for November shows some positive signs which, in a sense, highlight how bad the year has been. The past six months have been flatlining at best. At least November’s sales were a tiny bit above November 2022’s poor sales.

All of this puts the Party in a precarious position. For so long, the feeling was that central government policy would not boost the economy, but it certainly could. This started with the decision to keep the country locked down for years while most other nations had already relaxed Covid restrictions, but it extended beyond that to Beijing’s reluctance to pump up the ailing property sector. Now it seems officials are willing but unable to reignite China’s spark. We see this not just in consumer default numbers but in goods exports too, for which volumes are incredibly high but revenues are still uncomfortably low.

This weakness is surely one of the main reasons China has been so conciliatory toward the west in recent months. There have been multiple opportunities for tensions to flare up over Taiwan, but things remain calm. Also, it is hard to see President Xi’s meeting with President Biden last month – his first visit to the US since early 2017 – as anything other than a big peace offering. Trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies may well continue, but they are likely to be pushed much more by Biden than Xi. For the global economy at least, conciliation is a positive. But for China, its underlying weakness seems worryingly hard to address.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.