Published

2nd December 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –2nd December 2024

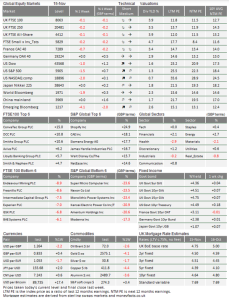

Equities and bonds go separate ways

Global financial markets appreciate the USA’s Thanksgiving holiday, which tends to be the quietest of its

unique holidays. Markets can be frenetic in the lead up though, as it proved last week.

Although developed market equities were calm in sterling terms, stocks were more turbulent in local currencies. France was notably hit by the fragmenting of its ruling parliamentary ‘alliance’. Emerging markets were even less happy, partly thanks to Trump. Brazil was the weakest, after President Lula announced softer-than-expected spending cuts, threatening future fiscal stability.

Japanese stocks were volatile, opening last Wednesday’s trading down 2.5% from the previous Friday’s level in Yen terms. This was directly offset (indeed, probably caused) by currency strength. The Yen notably strengthened against the US dollar, going from Y154.5 to Y150 (meaning it takes fewer Yen to buy $1). Since Wednesday’s weak opening, however, both the Nikkei 225 index and TOPIX index are up by 1% in yen terms and 1.5% in Sterling terms.

It seems to us that bonds and equities are being driven by differing narratives at the moment, particularly in the US. Commentary around economic growth is resolutely upbeat, helping equities. Meanwhile, the narrative around government debt has turned more positive but driven by the idea that the deficit may fall.

Lower US bond yields, which made the Yen more attractive, were caused by Donald Trump’s nomination for Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent. For bond markets, this is the most credible nomination Trump could have made. The erstwhile hedge fund manager has many fans. Some liken him to Reagan’s Treasury Secretary, the legendary James Baker, others think he’s more like Santa, expecting his nomination to gift further gains for US equities through December.

(Bessent worked for George Soros in the 1990s and as his CIO between 2011 and 2015, and is well regarded on Wall Street for his level headedness during periods of global market upheaval, with a profound knowledge of the inner working of the global economic framework)

His “3-3-3” plan is to raise growth to 3%, cut the government deficit to 3% and increase energy production by an equivalent of 3 million oil barrels per day, all by 2028. This is probably not achievable, but the investors see the aspiration as good for policy in each area. “3-4-1” is more achievable and less likely to risk a recession.

Regardless, the US 10-year treasury yield which had risen significantly from 3.8% since Trump’s election, dipped sharply to below 4.25%, with commentators linking the move to Bessent’s deficit reduction target. The spread to swaps, which we use as a measure of Treasury market credit risk, fell back to +0.52% from the previous week’s 0.57%.

Still, risk-free 10-year real yields (inflation hedged) also fell noticeably from 1.52% to 1.41%. That signals investors are less afraid of fiscal laxity, but less convinced about longer-term growth too.

Bessent wants growth through deregulation, and the last “3” on his plan – energy disinflation through increased supply – is a significant part. Bessent’s framework sees energy (electricity generation) as the supply constraint holding back US growth in a technological world, and Trump calls the solution “energy dominance”.

If inflation falls consistently below 2%, Fed interest rates should be relatively accommodative, keeping interest costs and bond yields well below nominal growth. That in turn should allow companies to borrow at attractive rates, making businesses more viable. The government could also reduce its debt load (at least relative to GDP) and lower its debt servicing expenses. The consequence would be rising corporate debt but higher levels of private business investment.

All of this paints a rosy picture and, perhaps counterintuitively, one that could benefit Europe and the UK. However much the US is struggling for energy supply, we are struggling more – Europe-wide wholesale electricity prices are about four times those of the US. If US prices fall, ours should fall by a similar proportion. The fall in Europe’s energy costs could therefore be four times greater than the US. The wider question, though, is the damage this does to emission reduction targets, and how much environmental disruption undermines the growth targets.

Even if the US puts up tariffs, the biggest barriers for European growth are internal supply constraints and productivity. If those go down, European growth should benefit – so a win for the US should be a win for Europe too, as long as politics doesn’t prevent it.

Politics, unfortunately, is an issue. France’s continued politic maelstrom looks similar to the US in recent years, the political right battling for cheaper energy while facing what they see as “lawfare”.

Last Thursday (28th November) after extreme pressure from his coalition partners in Le Pen’s

Rassemblement National, Prime Minister Barnier rescinded his proposed electricity tax at a budget cost of

€3.8bn. That threatens to derail attempts to bring down France’s unsustainably high budget deficit.

Investors see France as struggling more than the rest of Europe. Government bond yields fell across the Eurozone, thanks to falling US yields, but French yields did not shift as much.

The big political conundrum – in the UK, Europe and US – is now how to tighten budgets back to pre- pandemic levels without hurting jobs or smaller businesses. France’s electricity tax was unpopular, as is the UK’s decision to tax jobs – although Chancellor Rachel Reeves can more credibly say there will be no more.

The fact that the UK government will almost certainly be stable and internally cohesive for more than four years also helps. The US is nominally in the same position, but many doubt Trump’s administration will be internally cohesive.

Europe’s political instability is a problem. At the moment, it seems that the old mainstream political forces of the centre and left cannot form cohesive alliances, so new populist forces could gain more influence next year. Germany’s early elections take place on 23rd February, and it is unclear how a reconstituted “rainbow” coalition could work with CDU’s Merz as leader. Meanwhile, France is surely set for another election.

Investors do not see much upside in Europe, but there are seeds of positivity, which could grow into bullishness in the spring.

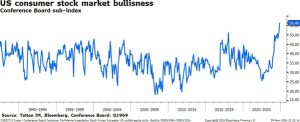

Lastly, we note that some (but not all) measures of bullish market sentiment are reaching extremes. Last week, the US Conference Board published its Consumer Confidence indices, which includes a measure of consumers’ expectations for stock market price rises. The chart below shows the current historically unprecedented bullishness:

Signals of potential exuberance are not great timing indicators, yet one shouldn’t expect that such bullishness will mean imminent disappointment. The same was true in March and July but selling US equities would have not been a good decision. Nevertheless, it could lead to higher volatility if we do see disappointments. We remain cautiously optimistic, as we have been since the start of the year.

Terrifying Tariffs

Donald Trump has started issuing policies before his inauguration. Last Monday, he proclaimed on Truth Social:

“On January 20th, as one of my many first Executive Orders, I will sign all necessary documents to charge Mexico and Canada a 25% Tariff on ALL products coming into the United States, and its ridiculous Open Borders.”

“This Tariff will remain in effect until such time as Drugs, in particular Fentanyl, and all Illegal Aliens stop this Invasion of our Country!”

“Both Mexico and Canada have the absolute right and power to easily solve this long simmering problem.”

“We hereby demand that they use this power, and until such time that they do, it is time for them to pay a very big price!”

Trump’s new tariff threats seem to violate the US/Mexico/Canada Agreement (USMCA) on trade, which he signed in 2020. The USMCA replaced NAFTA which had engendered largely duty-free trade between the three countries. During the bad-tempered talks that led to USMCA, temporary tariffs were imposed, and the nations could only agree a deal with a “sunset” provision to renegotiate in 2026. So, it was always going to be short term; it might just prove even shorter than planned.

Mexican President Sheinbaum responded immediately, saying that Trump’s tariffs would create inflation and job losses “until we put our common businesses at risk”. She warned they could cost 400,000 US jobs, as a tit-for-tat response to any imposition would be immediate.

For his part, the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said last Tuesday that he had spoken to Trump in a phone call on the previous evening. “We talked about some of the challenges that we can work on together. It was a good call,” Trudeau said. “This is a relationship that we know takes a certain amount of working on, and that’s what we’ll do.”

Trump also threatened more tariffs on the usual foe, China:

“I have had many talks with China about the massive amounts of drugs, in particular Fentanyl, being sent into the United States — But to no avail… Until such time as they stop, we will be charging China an additional 10% Tariff, above any additional Tariffs, on all of their many products coming into the United States of America.”

It was not clear if this “additional 10%” is on current levels or added to the 60% blanket tariff on Chinese

goods he promised during his election campaign. How might these impact trade?

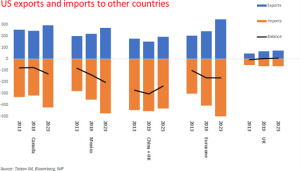

Mexico and Canada are extremely important to US exporters – even more so than China. Below is a graph showing US exports and imports (in US $bn) to Mexico, Canada, China, the Eurozone and the UK. The black lines are the US trade balance (exports minus imports).

Even though US trade deficits have mostly widened over the last 10 years, exports have grown and are significant to the economy. Canada and Mexico collectively bought $560bn of US exports and each is a larger market for US businesses than China.

Given the similarities of many goods traded between North American countries, it might seem simple for companies to replace overseas markets with domestic buyers. However, a wealthy Mexican is not likely to buy a cheap Mexican-produced car. Goods (and services) are not easily replaceable – if they were, it probably would have already happened.

A swift imposition of tariffs places huge strains on the affected companies and some, possibly many, will not survive. While the pain will almost certainly be greater outside the US, it will still be felt by a large number of businesses that probably felt they ought to be winners under a Trump administration. The threat to North American trade has wide and potentially unintended consequences; for example, a weaker Mexican economy might incentivise more, not less, immigration.

There is, perhaps, some wider potential consequence. For the US, the upside to free trade is the world’s acceptance that US companies should have access to their markets. Some of that access is almost unnoticed. The world’s use of Android and Chrome is not completely included in trade data because most of the revenue is collected by Alphabet’s overseas subsidiaries. The profit flow is counted in the current account as primary income when it is repatriated.

| Company | Last 12-month profit (estimated net income $bn) | Approximate non-US profit proportion |

| Apple | 96 | 60% |

| Alphabet | 87 | 54% |

| Microsoft | 84 | 50% |

| Nvidia | 60 | 80% |

| Meta | 51 | 56% |

| Amazon | 47 | 15% |

| Tesla | 8 | 40% |

| Mag7 | 433 | 54% |

| S&P 500 ex Mag7 | 1640 | 40% |

| S&P 500 | 2073 | 43% |

| Source: Tatton IM, Bloomberg 28/11/2024 | ||

By our calculation, five of the Magnificent Seven tech companies generate more than 54% of their profits from outside the US, while 40% of the S&P 500’s aggregate profits comes from overseas. It is no wonder that profit growth is more closely aligned to global growth than US growth.

While it is difficult to imagine how we might do without them, the moat of all of these intensely profitable tech-related companies is not so deep that they cannot be overcome. Trump is already incentivising the world to have a go, as seen by Huawei’s adoption of its own operating system for its phones.

The US imports huge volumes of low margin goods, but also receives huge profits for the services it exports to the global tech audience in return. A fight back by the world may end up taking away the source of the US’ enormous economic outperformance of the past 15 years.

We do not think, however, that tariffs will play out exactly as Trump threatens. His statements look more like “The Art of The Deal” than a manifesto – in particular the focus on dangerous drugs, which have afflicted many of the areas that voted for him. Tariffs are being used as the leverage to force other countries to take specific action on drugs (and immigration, although that seemed to be an afterthought), rather than trade imbalances.

Trump’s pick for Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, said as much even before the election. “The idea that he would recreate an affordability crisis is absurd,” Bessent told Axios’ Mike Allen in a phone interview last month. Bessent said that Trump “regards himself as the mayor of 330 million Americans, and he wants them to do great, and have a great four years.”

He also told the Financial Times that, in his view, Trump is “at the end of the day, a free trader”; the tariffs

were a starting point for negotiations.

There is a danger that the tariff lever is pulled too hard and too often. But for the moment, we should expect more of the same in the coming months and remember the assessment principle that worked quite well during his first presidency: Take what he says seriously but not literally