Published

9th September 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

Nervous markets ahead of second pivot

Capital markets have started September rather despondently. It feels similar to (though not nearly as bad as) the sell-off that started August, after which stock values quickly recovered. There were risks and headwinds back then, but nothing that significantly dampened the long-term outlook. This is even more true now: there are lots of uncertainties, but little that should materially concern investors. After August’s early sell-off and eerily strong recovery, we said markets should be generally positive in the months ahead – but further bouts of volatility were likely. Nothing last week has disturbed that view.

China continues to weigh on growth – and the world gives it little support

Markets are clearly nervous about slowing global growth, but this has been a feature for some time. It is most obvious in China, and there were more signs of weakness last week. Several big investment banks have downgraded their outlooks for Chinese equity, after second quarter profits shrunk by their largest amount since the end of 2022. Profits are expected to pick up again, but not by as much as analysts thought at the start of this year.

Weak iron and steel demand is probably the clearest sign of China’s struggles. Sentiment among steel producers was negative in July and worsened in August. The Chinese government has been reluctant to substantially support growth and their main lever for that support – stimulating industrial production – is worsening the global oversupply problem. The overhang of China’s unsold inventories is a major headwind for goods manufacturers across the world, and slowing demand for materials is affecting emerging market (EM) commodity producers.

US consumption has been surprisingly strong in the post-pandemic period and, in the past, that would have benefitted Chinese exporters. But tariffs brought in under successive US administrations have weakened that line of support. Things could get worse if Donald Trump is re-elected, with his promises of a 60% blanket tariff or higher on all Chinese goods. The realignment of US-China trade has been a benefit to many EMs as global companies relocated production from China, but EMs in Asia might feel some indirect pain from further deterioration – and perhaps some direct pain if Trump hikes tariffs on them too.

How long can services strength last?

These trade and disinflation problems are weighing on manufacturers globally. Auto manufacturers are the prime example; last week Volkswagen said it was considering shutting factories in its German heartland. German carmakers shutting domestic production is visceral sign of the industry’s troubles, given its cultural and political importance. But the problems are global, and even US manufacturers are under pressure.

Still, the service sectors have managed to hold up well through this period of manufacturing weakness – particularly in the US. The resulting earnings resilience has been good news for markets and the US economy – as they form the largest share of both, and are the backbone of employment. But the sell-off last week may be in part driven by a fear that the downturn will spread to services. There are some tentative signals that this might happen – core service inflation has slowed quite quickly, and labour market pressures have eased – but nothing conclusive. Markets seem worried about what will happen if manufacturing stays this weak.

Of course, the reaction could go the other way around – resilient services eventually leading a manufacturing recovery, as markets have predicted for most of 2024. The Fed pivoting to lower interest rates would help that, and bond markets now imply more than a 50% chance of a 0.5 percentage point interest rate cut (rather than just 0.25) at the Fed’s meeting in two weeks. But the risk of services weakening challenges the ‘goldilocks’ narrative that investors have embraced for so long. It was hoped that rates would come down while real growth remained – buoying equities – but now the real growth component is being challenged.

The US may struggle to keep shining

That risk is why the Fed has so clearly signalled its intention to cut rates and support the economy. Indeed, the pivot towards lower rates looks a little misplaced without that context, considering the world-beating performance of US growth and markets over the last few years. After such prolonged outperformance, it seems strange to think that the US economy needs help (many commentators still doubt it does). But as JP Morgan analysts recently pointed out, US employment and core services inflation is now weakening more rapidly than elsewhere.

That might just be because the US is starting from a much stronger point. But it could also be down to factors like fiscal support wearing off and pandemic-era savings being depleted. In any case, continued US exceptionalism is not guaranteed. You could view the momentum shift against big AI stocks in this light. Last Tuesday, Nvidia recorded the biggest ever single-day market cap loss of a stock, shedding $278.9 billion after its share price dropped 9.5% on the day.

A potential end to US outperformance would hurt international investors – since American stocks are such a big component of global portfolios. Investors will know as much from big tech’s troubles in the summer and their 2022 downturn.

But there are positives for global markets or the economy. A weaker dollar usually supports global growth, for example. We could end up in a similar situation to 2014-16, when energy and commodities struggled, and several big industries were caught in the fallout – but, overall, there was a real income boost which stabilised the global economy.

The next fortnight will be about central bank meetings and in particular whether the US Fed delivers on their signposted second pivot by lowering interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) kicks off proceedings on Thursday 12th, followed by the US Federal Open Markets Committee which meets on Wednesday 18th , and the Bank of England (BoE) on Thursday 19th. The ECB is expected to cut by 0.25 percentage points, bringing the deposit rate to 3.5% and overnight bank rates to just above 3.4%. The BoE is not expected to move again after cutting the base rate by 0.25 points to 5% on 1st August.

The Fed will cut its Fed Funds target band by at least 0.25 percentage points at its meeting. The band is currently 5.25%-5.5%, with the “effective” rate just over 5.3%. Last week’s soft employment data culminated in a non-farm payroll (the number of new private and government agency jobs) gain for August of 142,000, below the expected 165,000. This decline in employment gains is not horrible but, together with slowing inflation and no rebound in manufacturing, it suggests that rates need to be lower, ultimately down to about 3.5%. The risk of inflation rebounding has faded quickly, so we think the Fed will probably cut its funds rate by 0.5 points, to an effective 4.8%.

Changes to the previous expectation set like this, can scare markets in the short-term – as investors start to worry that the Fed knows something bad us mortals do not. Others think the Fed might already be behind the curve of a slowing economy, but this is a scenario the central bank has analysed and prepared for. Its well-researched playbook says it is better to act decisively and quickly when faced with a downturn, so we should expect policymakers to do so. Rates are therefore set to fall and as already stated more likely by 0.5 percentage points than 0.25, as the Fed is now more attuned to downside risks. A more active Fed is a good protection and investors will surely take comfort in that.

August market returns review

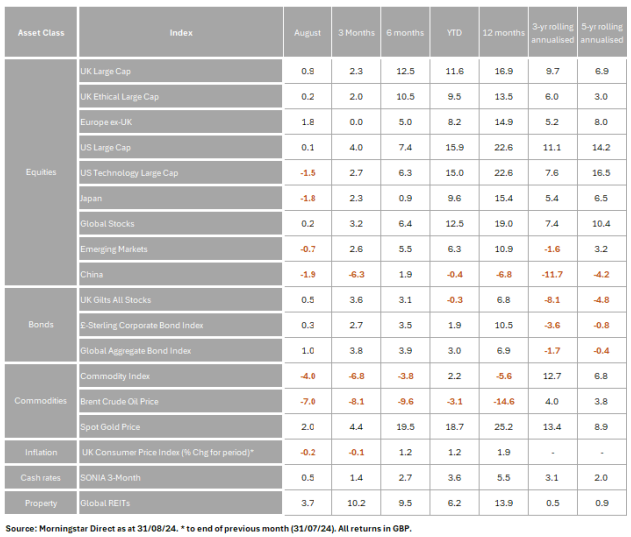

August was a rollercoaster ride in capital markets and, like an actual rollercoaster, it ended where it started. Capital markets were more volatile at the start of the month than they have been all year, but monthly global stock returns were virtually flat at 0.2% in sterling terms. The ride was at its most extreme in Japan (volatility over 62% annualized, for the month), but the pattern was largely the same across most major regions: a big sell-off in the first week followed by a remarkably steady and historically unusual climb back up. The swings were not fully even, though, with Japan and the US tech sector finishing down, while Europe and the UK finished up. The table below shows August’s major asset class returns in sterling terms.

Early volatility was ignited by a mixture of market liquidity problems and concerns about slowing US growth. Markets were unnerved by weaker than expected US jobs data, which came shortly after the Bank of Japan raised interest rates at the end of July. Ultra-low Japanese rates and a steadily weakening yen had been propping up the ‘carry trade’ (borrowing cheaply in yen and investing the money in higher yielding regions like the US, to net the difference) but shifting monetary policy unwound those positions.

This culminated in Japanese stocks declining more than 12% on 5th August. That sell-off reverberated around the world, amplified by US recession fears.

Japan’s unwinding carry trade was cited as the markets’ main liquidity drain, but we note there were other sources too – most notably the People’s Bank of China maintaining tight financial conditions to support its currency, and some lasting effects of quantitative tightening in US treasury markets. In any case, intraday volatility – as measured by the VIX index – rose to its highest level since March 2020!

These liquidity problems were ultimately short-lived, however, and the recession fears always looked overdone. More positive economic data through the month, together with supportive central bank messages, led to markets regaining ground. The recovery was incredibly smooth – unexpectedly so. Volatility dropped as quickly as it came, and the stocks recorded an unusually long winning run (days of consecutive gains) mid-month. This goes against the usual post sell-off pattern, in which volatility gradually comes down like a slowing pendulum.

European stocks were the best performers on the month, jumping up 1.8% in sterling terms. Softer inflation data increased market expectations that the European Central Bank (ECB) would cut rates for the second time in their September meeting. Indeed, markets’ implied path for European rates moved sharply down, pricing in multiple cuts before the end of 2024.

UK rates are expected to keep falling, but not as steeply as on the continent. UK stocks gained nevertheless, with large stocks in the UK Large-Cap index finishing up 0.9%. This makes British stocks the best performers over the last six months – up 12.5% – after a prolonged period of UK underperformance. Notably, recent UK equity strength has coincided with stronger business sentiment surveys than elsewhere.

The weakest major equity region was once again China, dropping 1.9% in sterling terms and continuing its long period of malaise. China’s sluggish economy also contributed to Brent crude oil prices losing 7% in August (along with unexpected growth in US stockpiles) and, we suspect, to a new record high in gold prices. Chinese citizens have been buying gold for some time as a cash alternative, due to a lack of confidence in the renminbi. We note, however, that China’s currency strengthened greatly into the month’s end, a sign that confidence might be returning.

Large US stocks managed to regain all of their early August losses, finishing virtually flat at +0.1% in sterling terms. But US tech stocks did not fully recover, losing 1.5% in sterling terms. In fact, if you exclude the ‘Magnificent Seven’ (Apple, Alphabet/Google, Amazon, Meta/Facebook, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla), the other big US stocks (sometimes called the S&P 493 – the S&P 500 without the Mag7) performed very similarly to Europe. This suggests that the Mag7 have become a unique class of their own as far as stock market analysis is concerned. It also tells us that market breadth widened across regions in the aftermath of the August selloff, as the former non-tech laggards started to catch up with the hitherto best performers of the year.

Japan also failed to claw back its losses, finishing August 1.8% lower in sterling terms. That losses were only so low, however, is impressive considering the crash at the start of the month. The BoJ responded quickly to the rout by promising not to raise rates in periods of market instability.

Some commentators called this a capitulation from the BoJ, and argued it might undermine their long-term goals (unwinding the yen-dollar carry trade is probably a long-term good for Japan, for example) but it undeniably helped support Japanese markets. We remain positive on the long-term case for Japanese stocks.

In general, central bankers took a decidedly dovish turn in August, and markets now expect an easier rate environment ahead. That, more than the early volatility, will be the month’s lasting impact. Even though turbulence faded quickly, we suspect there may be more ahead – as growth is slowing and rates are still historically high. But the long-term picture remains supportive.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.