Published

17th June 2024

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly –17th June 2024

Still mostly sticking to the plan

After a cacophony of political noise, central bankers were again the ones to really strike a chord with capital markets last week. Britain’s political parties unveiled their manifestos and French President Macron shocked everyone with a surprise election call – causing fairly significant market consternation – but it was an updated interest rate forecast from the US Federal Reserve (Fed) that turned out to be the key driver of markets. The Fed signalled it would cut interest rates just once this year, disappointing those who were betting on two cuts. This was called “hawkish” by the media, but we think “bullish” is probably more appropriate. It was more about recognising economic strength than a preference for higher rates.

UK underperforms, but don’t blame elections

First off, we should say something about manifesto releases from Labour and the Conservatives. UK investors are understandably anxious to hear how the election and future government might affect their portfolios, but the answer is, once again, probably very little. Labour is expected to win a majority, but not change much about the UK economy, or the fiscal position as far as asset prices over the short-to-medium term are concerned – particularly when compared to the market upheaval the ill-fated Liz Truss government managed to cause. The policy-lite manifesto Keir Starmer’s party unveiled last week did nothing to change those expectations.

Interestingly, the few weeks since Rishi Sunak announced the election have coincided with a pretty dour period for UK stocks, and right after a period of outperformance for UK assets, too. But this is probably a coincidence. Britain’s biggest stocks did well in previous months because the group is dominated by banks, multinational energy and commodities companies – stocks that usually do well when the wheels of the global economy turn to expansion. Global growth positivity has slowed in recent weeks, with a distinct shift back to the US megacap stocks, with their seeming immunity to economic downturns.

On the plus side, UK stocks still have cheap valuations compared to international peers, and the longer-term growth case is not damaged (in fact many economists suspect it might be marginally improved) by the widely expected imminent switch in government. What the Bank of England does will be much more important for UK assets and, on that front, it looks like the bank has more room to cut rates than international counterparts. Recent inflation data was barely above the 2% target, and markets are evenly split on whether the BoE will cut this month.

Fed signals economic positivity – not hawkishness

After multiple signals that US inflation had come down significantly, markets thought the Fed would validate their implied expectations of two quarter-point rate cuts this year. But the Fed’s ‘dots plot’ – which shows committee members’ expected rate paths over the next few years – revealed that officials expect to cut rates just once in 2024.

This was called a “hawkish” move by financial media, but US stocks still ended the week up. This is because the Fed’s update was more about acknowledging the US economy’s strength and resilience than turning hawkish. Indeed, in the press conference, Jerome Powell acknowledged that recent economic data had been soft – perhaps a signal that he personally would be inclined to cut rates sooner rather than later.

Some recent US inflation data has indeed been soft – including May’s CPI print of 3.3%, released only a few hours before the Fed’s dots plot announcement. But other sources are still pointing toward US strength, such as the outsized jobs increase reported recently: 272,000 jobs were added in the US last month, smashing expectations of 185,000.

It is an open question whether this job market strength will lead to renewed inflationary pressure. What is not up for debate, however, is that the US economy is stronger than other regions and still stronger than most expected it to be at this stage of the cycle. This strength is giving the Fed pause. As the dots plot shows, officials still plan to cut rates this year, but they need to see more evidence that the current gentle slowdown in US growth is sufficient to keep inflation from flaring up again.

That makes perfect sense, and markets are unlikely to interpret this as a negative signal about the US economy or financial conditions. Central bankers are sticking to the rate cut plan, just getting more realistic about how, when and to what magnitude it can be implemented.

Investors flock back to tech megacaps, a possible warning sign for global growth

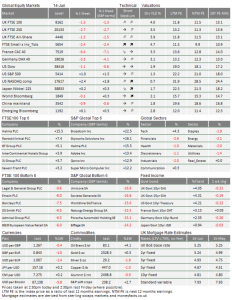

The Bloomberg World Equity Index is showing a tiny overall gain since the beginning of last week in Sterling terms, but the distribution of returns across sectors and regions is skewed. Across the board, stocks are more down than up, with just the top 5 positive contributors – Apple, Broadcom, Nvidia, Microsoft and Taiwan Semiconductor – skewing the markets overall back into positive territory. The most negative contributor has been JP Morgan, but most of the bottom quintile come from Europe.

LVMH was Europe’s worst performer. The luxury goods company is caught between a rock and a hard place, with its home base being disrupted by Macron’s remarkable decision to call for a parliamentary election (upon which we write below) and yet more signals of poor demand in its biggest market, China.

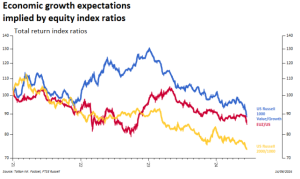

Europe has done badly during the last week, France leading the way down with a 5% loss. Often, as Europe is more cyclical than the US, underperformance can be related to slower global growth expectations (see red line in the chart below). One might expect slower growth in Europe, given the political upheaval, but there are also other signals of slower growth expectations. In the US itself, the Russell 2000 (the 2000 stocks with market cap below the top 1000 in the Russell 1000 index) has been slipping back relatively since the start of May and absolutely since mid-May (the yellow line shows the Russell 2000’s relative performance). And within the top Russell 1000 index, the value-oriented stocks have been underperforming the growth stocks (shown by the blue line).

Together, these signals seem to add up to weakening investor perceptions of the economic growth outlook globally, and even within the US. This went hand-in-hand with the recent decline in global bond yields – at least until political uncertainty intervened. On Friday, we have the release of the latest business sentiment readings in the form of the “flash” regional purchasing manager indices. It seems to us that these more forward-looking data could set the scene for the equity markets through much of the summer, coming just as we head into the Q2 earnings season.

Following the very strong run, markets feel a little fragile. It has been powered by a strong run up in earnings expectations which is starting to seem questionable given the run of softer economic data. However, it is perfectly possible that the data could start to turn better, much as it did this time last year. Should that be the case, we would see the pro-cyclical assets – ie. the laggards of the rally of the past 12 months – do well, with a lot of room to rebound from the recent underperformance.

Macron makes an educated bet

We wrote last week about elections upsetting markets and preached calm. But during the past week saw surging support for far-right parties at the European parliament elections, and a surprise snap election call from French President Macron, resulting in a significant sell-off in European assets. When it rains, it pours.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen’s centre-right bloc ultimately won the most votes and seats in European parliamentary voting, but exit polls showed a record number of seats going to far[1]right or Eurosceptic parties. The surge was particularly stark in France, where Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) party won the largest share of votes and parliamentary seats – with Macron’s pro-European list a distant second, barely ahead of the third-placed socialists.

Macron’s response was bolder than anyone expected by calling a snap election for France’s national parliament. With first round of voting by 30th June the president seems to be throwing down the gauntlet to Le Pen and her protégé Jordan Bardella, the 28-year-old leader of RN. A brazen Macron explained his reasoning in a news conference last Wednesday: “I do not want to give the keys of power to the far right in 2027, so I fully accept having triggered a movement to provide clarification.”

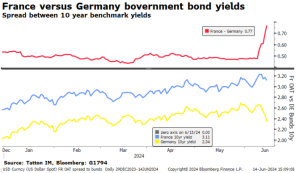

Markets could certainly do with some “clarification”. The euro weakened against the dollar into the start of last week, and French and Italian government bond yields rose most among those whose far-right parties saw a bump in the European elections (although it is interesting that German yields fell despite the AfD’s strong performance).

The result was a sharp move down in French stocks, losing 1.4% last Monday, and European stocks more broadly. Victory for the populist and Eurosceptic RN is presumed to be a bad outcome for capital markets, which typically prefer a free-trade oriented status quo – certainly for EU states.

Commenting on election-inspired market volatility last week, we noted that, historically when markets have got upset about politics, it tends to be short-lived. A weaker-than-expected showing for assumed ‘preferred’ result by investors can create sharp sell-offs, but these are often overreactions and the recovery can be a good short-to-medium-term buying opportunity – as shown after the Brexit referendum and Trump’s 2016 victory. We broadly stand by that assessment in the case of France, but we would add that volatility is likely at least until the final round of voting on July 7th .

Investors famously hate shocks and uncertainty, and the last week alone has had enough twists to fill a soap opera. Last Tuesday, the head of France’s established conservative party, Éric Ciotti, called for an alliance with Le Pen and the RN. Bets on an RN-led parliament jumped, and French stocks continued their sell-off. But the suggestion enraged Ciotti’s party and they voted to oust him on Wednesday. The drama turned to a farce, as Ciotti shuttered the party HQ due to apparent “threats” and the party committee, forced to meet in a nearby building, warned they would physically remove him if necessary.

Markets’ biggest fear about a RN victory seems to be a fiscal crisis. Macron’s finance minister played up those fears last week, warning that under RN’s plans a “Liz Truss-style scenario is possible”. France’s bond sell-off suggests investors feel the same.

That is a risk, but we should not get carried away by hyperbole. Italy’s populist government, for example, has kept Italian bond yields fairly stable compared to European counterparts, despite similarly dire warnings after the nation’s 2022 election. Moreover, other market researchers have pointed out that the impact of an RN victory for French companies might be relatively small. Barring a short-term budget crisis or – worse – threats to leave the EU, the medium-term effects on French and European stocks will likely be mild.

The long-term picture is much harder to work out, as it depends on so many unknowns. Chief among them is what the upcoming election will mean for the next presidential vote in 2027. By calling a parliamentary election now, we suspect Macron is making an educated bet about his future: either he beats RN and firms up his centre-right alliances ahead of 2027, or his party loses and voters have three years to grow tired of a populist government. Either way, the president seems to think that his chances will be better now than if he left support for Le Pen and Bardella fester.

That is a plausible outlook on what might happen, but it is a gamble. The risk for Macron is that an RN-led parliament spends years fighting the executive at every turn and successfully blames the deadlock on him. The risk for markets is that this heightens bond volatility, and increases the anti-EU sentiment in the bloc’s second-largest economy.

We have seen in the US that a disjointed and polarised political system is not necessarily a barrier for strong economic and financial growth – but France is not the US. Its economy does not have the same depth and dynamism needed to tumble through political crises unscathed. There are good reasons to think the fledgling European growth recovery will carry on undisturbed by French politics. But volatility is likely, in the short-term at least.

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.