Published

4th September 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 4th September 2023

New school term has the US back at the top of the class

Summer is officially over, but we are none the wiser regarding the direction of the economy. Or are we? Well, we quite likely are, but just a bit and not enough to know if next month’s equity markets will be higher or lower than right now.

We will write about August’s asset class performance in detail next week, as data gathered at the beginning of the month is usually still somewhat unreliable. Nevertheless, the broad outturn was slightly negative with US stocks ending the month unchanged. India was the best performer by a very slight amount, but perhaps more importantly, it has shown a lot of price stability recently with the underlying economy doing well especially in export terms. This is somewhat different to other Emerging Market nations which have been more impacted by a slide in global goods trade. We write about India in the second article this week.

In the UK, house prices continue to decline as evidenced by the 5.3% year-on-year fall in the Nationwide August index reading. Prices fell 0.8% in August and the softening of the UK labour market suggests the falls could continue into the colder months as affordability further decreases. Although fuel prices have moved annoyingly higher in recent weeks, food prices appear to have stabilised somewhat with grain prices falling over 10% in sterling terms over the past year.

Generally, the UK’s inflation backdrop continues to ease, although not fast enough for comfort according to Bank of England (BoE) chief economist Huw Pill. He wants interest rates to remain high and steady (like the Table Mountain in Cape Town – where he made the speech); and suggests policy should be kept steady at restrictive levels rather than sharp hikes followed by rate cuts. Pill argues that the tight jobs market allows workers to push up wages which have previously been eroded by inflation, creating a dynamic that leads to inflation persistence.

Bloomberg reported that Pill said the BoE takes comfort from longer-term inflation expectations being much better anchored compared to previous surges in prices in the 1970s and 1980s. “That’s something we have to work on,” he said. “That anchoring of expectations doesn’t happen by accident. It happens because of the actions of the central bank and the commitment of the central bank to its inflation target.” Regardless, perhaps we should be happy he did not mention any immediate need to raise rates further.

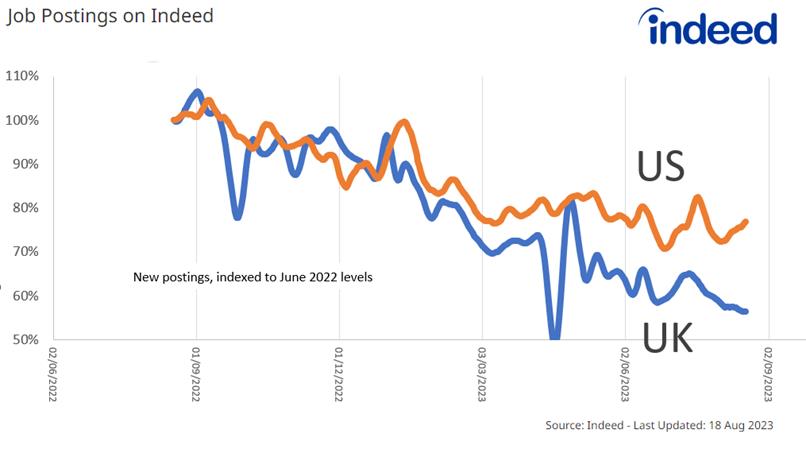

In terms of wage dynamics, one of the data sources for the employment market we observe most closely is the Hiring Lab team at Indeed. Their data shows how both the UK and US jobs market have eased but the slowing is more noticeable in the UK (see the chart below).

We conclude from this that – despite Huw Pill’s warnings – for the UK, the room for rates to come down is closer than he may want to make his audience believe. There are still ongoing wage disputes, but these are fewer now that many of the NHS settlements have been done. Meanwhile, the UK government seems set on a mildly restrictive stance designed to help bring inflation down. For Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, this is a “must achieve”, so things may get even tighter.

However, the job postings data in the US market may be showing signs of picking up, despite the mild decline in the official August (non-farm payroll) employment numbers and the climb of unemployment to 3.8%. Bonds have been seeing yield declines through the week amid optimism that the US labour market is easing into non-inflationary territory, but the above chart suggests caution.

For us and for Steven Blitz, leading US economist at TS Lombard Research, the latest US GDP release contained an important signal – broad non-financial corporate profits rose in the second quarter, contrary to expectations. This is important because it appears the restraint on businesses and consumers imposed by higher interest rates has not been particularly impactful over the summer. Blitz argues that both companies and households spent the post Global Financial Crisis (GFC) years getting their balance sheets into good order, reducing debt and growing savings. That leaves the private sector in a good position, one which is not as much impaired by the cost of debt than has been the historic norm. Indeed, it seems that the private sector may be benefitting from the rise in interest rates, as interest income outstrips debt cost increases.

It’s the government and other public deficits which have worsened substantially. Of course, the pandemic would have always led to a sharp rise in debt levels but, for the US especially, the public sector balance sheet was already on a declining path following Trump’s expansive fiscal policy while cutting corporate taxes at the same time.

The extent of government deficits was a big topic at last weekend’s central bank get-together at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. We write about this in the first article below.

Large public deficits are not destabilising in themselves as long as confidence in the state institutions remains strong and the general financial environment is healthy enough to not deprive the private sector of the capital to grow. However, the current relatively large size of public debt relative to economic output across most developed economies give little room for emergency action if needed. We certainly would find another pandemic problematic.

More importantly and likely, the deficits have to be stable on an ongoing basis rather than expanding because of interest costs. In the US, revenues are just about adequate but projections of stability require an assumption that many of the Biden programmes have an endpoint. Such time-constrained spending programmes tend to get extended. Thinking that the US will move into recession because the government will constrain expenditure flies in the face of history, especially around election years. Europe’s position may differ slightly in detail but not broadly in direction.

However, there is a significant difference when we compare economic growth as all the above suggests that the US economy is not being obviously held back by the current higher rates. Whereas house prices are falling in the UK, the US-wide Shiller index of house prices showed another rise in the latest month (June data). The index has been rising since February and is now back to its previous high seen in June 2022. The nature of the US housing market is that housing purchases are mostly in new homes, which in turn is having a positive impact on growth.

Following significantly tighter financial conditions over the second quarter they have recently eased back as corporate lending premiums (credit spreads) declined on spreading expectations that the US economy will avoid recession. Profit expectations have started to rise as well on a next 12-month basis, partly because analysts are not bringing down their expectations for 2024 as they usually do as the year ahead draws closer. This may change, but recent guidance by companies is not compelling them to do so currently. While the stock market is giving high valuations to those profits, should profit growth prove to be achievable, equities would remain underpinned despite continuing high rates.

Such economic resilience despite all monetary tightening of the past year-and-a-half would not be comfortable for the US Federal Reserve (Fed). While Huw Pill may worry about the UK’s inflation persistence, the US economy would be far more likely to have a problem with sticky inflation as the labour market would remain tight. US bond yields may have fallen back recently on slight economic sogginess but we think it unlikely they will go too much further. Given the lag in economic dynamics in Europe and the UK, they have got more room to ease here.

So, are we any wiser at the end of months of seemingly economic procrastination, plateauing of interest rates, disappointing China news and fearing about imminent recession? Well, the general economic development has by and large withstood the monetary onslaught much better than expected while inflation has come down progressively. This tells us that despite widespread fears that after ten years of ultra-low interest rates, the return of ‘old normal’ levels of interest rates would spell imminent economic and market disaster are probably premature.

As a result, markets have been much like the past summer months in the UK – not so hot but not disastrously cooler. Companies and households have been prepared for difficulties but it hasn’t been so difficult. Let’s hope the autumn is full of warmth, mists and mellow fruitfulness.

Life and debt: an era of high public borrowing

At their annual mountain retreat the previous weekend, central bankers got existential. The conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming – described by the New York Times as the economists’ version of the Cannes Film Festival – saw policymakers mulling over not just immediate issues but the future of the global economy. According to European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde, worldwide trends toward tighter labour markets, regionalisation and the green transition have fundamentally changed the way monetary policy works. In her words: “There is no pre-existing playbook for the situation we are facing today – and so our task is to draw up a new one.”

Something this playbook needs is a way to deal with significantly higher public debt piles. In one of the conference’s most-discussed talks, The International Monetary Fund (IMF) economist Serkan Arslanalp and Barry Eichengreen, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, warned that the debts racked up by governments since the pandemic are going nowhere fast. Debt-to-GDP ratios have “soared to unprecedented peacetime heights”, but are likely to remain extremely high, despite the financial, economic and political problems they pose. According to their accompanying paper, “debt reduction, while desirable in principle, is unlikely in practice,”

In the decade after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), total government debts trended upwards around the world – despite austerity efforts – and there was little growth to inflate away the relative size of debt piles. However, the central banks of developed nations made sure interest rate levels remained appropriately low for the interest to not become a burden on budgets. This trend was supercharged by the pandemic, thanks to emergency monetary and fiscal measures in rich countries. The hope was that these would come down once the world returned to normal, but supply-side crises and acute inflation pressures put a spanner in the works. The UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio is now above 100% for the first time since 1960 (when finances were still recovering from the Second World War), while the US is at a record high of 129% according to the US Congressional Budget Office.

Bringing these ratios down meaningfully in the next decade seems unlikely. Governments would need to run primary budget surpluses, requiring growth in tax revenues or lower spending – ideally both. Or an extraordinary growth spurt, which means debt/GDP naturally diminishes as GDP outgrows debt. Neither looks feasible. The World Bank now expects slower growth over the long term, and indeed, investor hopes of lower inflation are arguably predicated on such sluggish growth. Meanwhile, calls for public spending have gotten louder rather than quieter. Ageing populations (and electorates) in developed nations – which require larger healthcare and pension payments – and much-needed investment in the green transition make spending cuts look fanciful.

The UK is a prime example of these dynamics. We are all aware of the need for public spending, both as a long-term investment in Britain’s sluggish economy and as ongoing upkeep for critical services like health and social care. At the same time, growth prospects have been slashed, drastically lowering the expected tax base with which we can pay for such policies. Barring improbable tax reform, the only way to front the bill is extensive borrowing. But since this borrowing would already start from a high base, and much of it would be earmarked for things other than improving productivity, the government would effectively be resigning itself to indefinite debts.

Higher interest rates are another barrier to debt reduction. Rates have soared in the last 18 months, from near-zero to just over 5% (short-term rate) in the US. Markets have long been looking forward to the day that central banks change course and were buoyed a few months ago by an apparent peak in rates, but US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell used his Jackson Hole speech to reemphasise his tightening bias – the ‘higher for longer’ mantra keeps being repeated.

In any case, the structural changes noted by Powell, Lagarde and others could mean long-term rates will be much higher in the next decade than they were in the last. Deputy Bank of England (BoE) Governor Ben Broadbent warned in his speech that inflation pressures would not fade as fast as they came, meaning interest rates “will probably have to remain in restrictive territory for quite some time yet”. The so-called neutral interest rate – which neither helps nor hinders growth – was a big discussion topic in Wyoming, with many suggesting that supply and labour market tightness have moved it up. Likewise, there is increased debate around whether the 2% inflation target adopted by most central banks is a good one.

Even if interest rates are manageable, this would only reduce debt if growth was sustainably above borrowing rates. This looks unlikely in the next decade, for reasons already mentioned. With tight labour markets and the increasingly devastating impacts of climate change (both first-round natural and second-round political), it is hard to see how high growth could come without equally high inflation. If we get both, interest rates would rise and neutralise the effects on government balance sheets. If we get neither, borrowing rates would be low but total debts would still be high – then a dynamic economists talk about as ‘Japanification’ would ensue. A rather neat way out would be if the current US equity market valuation for tech stocks were a harbinger of future growth based on a jump in productivity, based on artificial intelligence (AI), which would then increase GDP. This is being much debated, but quite often can only be observed in hindsight.

For similar reasons, Arslanalp and Eichengreen dismiss the notion that inflation could itself help bring down debt. The idea is that inflation ups the nominal value of GDP and thereby brings down the real (inflation- adjusted) value of outstanding debts. But over the long-term, this only increases interest rates or leads to more borrowing – as spending and investment requirements rise with inflation too. This exact scenario played out over the last few years, and we should not expect it to be much different in future.

Of course, none of these factors would stand in the way of a government reducing debt as their only priority. But such a government would be incredibly unpopular, at a time when faith in western democratic structures is already faltering. So, the paper notes, countries will “have to live with this reality as a semipermanent state.” Countries, however, do not “live” with the policies governments enforce; people do.

Ultimately, populations will have to accept one or more of the following: persistently high inflation, stagnating living standards, or higher tax rates. The first is famously politically unstable, while we have seen over the last 15 years how the second can undermine liberal democracy. The third is the more realistic option, but it requires social cohesion and faith in the political system. That has been hard to come by in recent years across the US and Europe. This side of the Atlantic, where tax burdens are already relatively high, increased tax burdens will be a hard sell. In the US – where politics is so divided that a third of Americans think a civil war is coming – it may be impossible. Where monetary policy goes in this environment is hard to say. We can hardly blame central bankers for getting existential.

Emerging markets – if not China, India?

Emerging Market (EM) investors have had a stressful year. China has dominated the EM commentary once again, as it so often does, but this time around with growth disappointment unwinding the market’s initial optimism.

Equity moves have been stop-start since the beginning of the year. MSCI’s Emerging Market index is currently down over the last six months, following a notable sell-off through August. The Chinese government promised yet more support at the end of July, but investors were perturbed by the lack of policy urgency amid a clear slowdown. The latest figures show that China’s manufacturing sector contracted for a fifth consecutive month (albeit by as much as in June).

The ailing property sector, perceived government overreach and worsening trade relations with the US have severely soured market sentiment. All in all, investors sold a record $12 billion worth of Chinese stocks last month, weighing heavily on the aggregate EM indices.

Last week we observed a reversal of some of the recent China narrative. There have been more forceful moves to underpin housing demand via an easing of mortgage rates and conditions. Meanwhile the trips to China by US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and the UK’s Foreign Secretary James Cleverly have signalled improving relationships, or at least a mutual intention in that direction.

But, what about the other EM nations? Because China dominates emerging market headlines and financial indices, some good performances from the other EM nations has been overshadowed. India in particular has had an impressive year, with strong and improving economic growth. India’s second quarter growth for 2023 was reported as 7.8%, above expectations of 7.7%, following 6.1% growth in the first quarter.

Economic optimism has fed through into its domestic equity market. The narrowly based Nifty 50 index has gained 10.3% over the last six months, despite the wider fall for EM equities.

As of August 2023, according to United Nations population estimates based on 2021 data, it became the world’s most populous country, growing at a staggering one million people per month. For context, China adds about 150,000 people per month. This is one reason why India’s economy has been powering ahead for quite some time too.

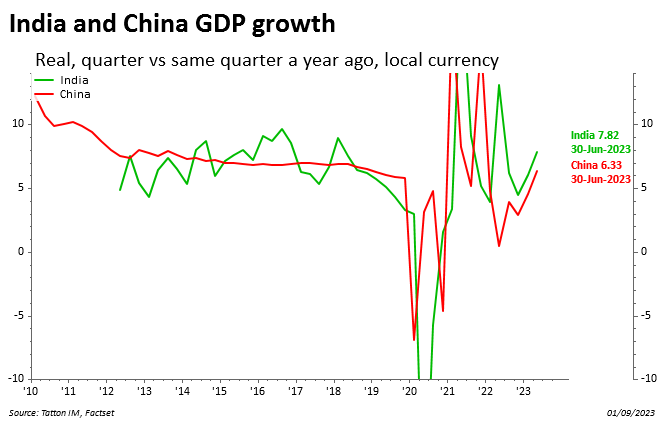

The pandemic period was highly volatile for both India and China, with India suffering a massive hit in 2020. But GDP growth in local currency terms has not dipped below 4% year-on-year since Q1 2021 – starting with a post-pandemic boom of 21.6% in Q2 of that year.

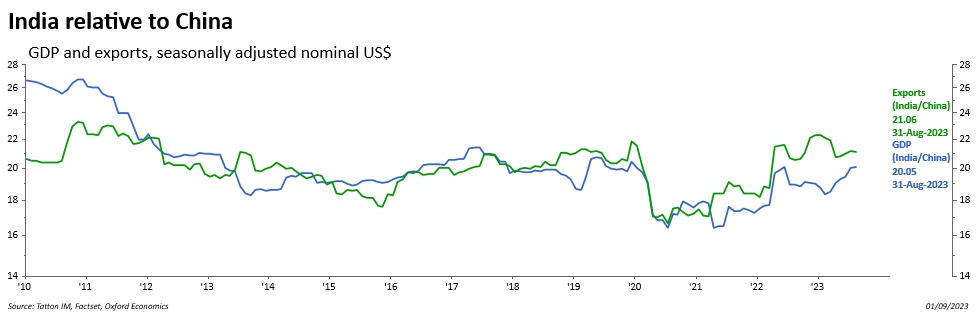

Exports of both goods and services have grown substantially (bucking the general global trend), while India’s government-led infrastructure push has helped demand and set the scene for better prospects ahead. The relative weakness of China, and Beijing’s increasingly aggressive attitude to its private sector, have also seen some reallocation of both trade and foreign investment. Tellingly, Indian growth has been higher than China’s since Q1 2022.

Exports have been at the heart of this growth story. According to researchers at TS Lombard, exports have grown at a compound rate of 12.5% annually since March 2020, compared to 4.5% for the wider economy. It estimates that exports account for 43% of India’s growth in that time. The next biggest factor has been capital investment, propelled by the infrastructure push and growth in residential real estate.

The fact India’s growth story has been so export-dominated is a concern for the future. The country was well placed to take advantage of booming western demand coming out of lockdown, but that makes it susceptible to weaker demand now. Global growth has been significantly slower this year, and this is already having an impact on Indian manufacturers. Manufacturing demand has slowed sharply, having held up well for most of the year.

TS Lombard note that the services sector is not quite strong enough to pick up the slack either. Services have improved following sustained economic expansion, but they are still some ways below the pre- pandemic projections, while goods producers are ahead of theirs. This can be seen in subdued services inflation which, unlike in most developed economies, has not followed through after the spike in goods inflation. Core inflation – excluding volatile items like food and energy – has closely tracked goods inflation in India, contrary to most other major economies.

India’s post-pandemic recovery has been undeniably strong, which has helped to underpin some long-term improvements, but the fact it has been so uneven has stopped some of the favourable growth forces from really taking route. Lower income households have not benefitted as much as those with higher income, meaning that domestic demand has been sluggish and lopsided. And consumption among richer households is now pulling back too, without poorer citizens getting enough of an advantage from the years of growth.

Unlike in the West, India’s labour market – particularly for lower skilled jobs – is fairly loose. Increasing employment would help support domestic demand, and private sector capital expenditure (capex) would go a long way to achieving that. Unfortunately, investment to this point has been largely government-led. It would be difficult to get a big improvement in this regard either, thanks to tighter monetary policy at home and abroad. Foreign direct investment into India has slowed over the last year, despite its impressive growth and relative attractiveness compared to other EMs.

These factors are complications, but not barriers, to future growth – certainly not in the very near term. On the capex front, we note that India’s corporates mostly have very healthy balance sheets, and lenders are keen to extend credit. The latest Reserve Bank of India (RBI) lending survey shows that standards have eased over the last two years, meaning there is certainly the potential for demand-supportive credit growth. India’s capex lag seems to be more an issue of willingness – perhaps due to pandemic scarring – than ability.

Should businesses decide to invest, the conditions could hardly be better. Near-term growth prospects are still very decent, helped by India’s recovery from a terms of trade shock last year. Moreover, waning inflation pressures following the global commodity easing – and the plateauing of RBI interest rates – should help support consumer confidence. If Indians can be confident in their job prospects too, domestic demand might well be able to take the lead after all.

Even if growth continues to come through, it could be difficult to extend the stock market rally seen over the last few months – thanks to higher valuations and difficult conditions for foreign investors. On this front, though, the relative position to China will no doubt be a meaningful contributing factor. Near-term growth prospects are arguably better in India, and political restrictions have already led many Western investors to switch their preferred EM. Further improvements could mean India wins even more capital bound for its geopolitical rival.

That said, President Modi’s government has many of its own issues that could put off Western investors. This has not happened to a large degree yet, but India’s eagerness to keep trading with Russia is a definite sour note. There is also the question of China-India cooperation through BRICS summits. The collective of Brazil, Russia, India China and South Africa announced its expansion at its summit the previous week, inviting Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — to join its ranks, and China and India agreed to remove troops from their disputed border. Strangely enough, after the US ramped up tensions with Beijing, it might be against India’s short-term interest to ease its own tensions with China.

Finally, notes of caution:

India may have more people, but its economy and exports are still only about 20% of its neighbour China.

Corporate governance issues abound there at least as much as they do in China. Some large cap Indian companies have majority free floats of shares, but most Indian companies do not, being run by family and other interests. The recent troubles that faced the Adani companies are an example of the volatility that will occur repeatedly for many years. It’s not a market for the faint-hearted and for all of the great growth, Emerging Market investing will probably remain so.

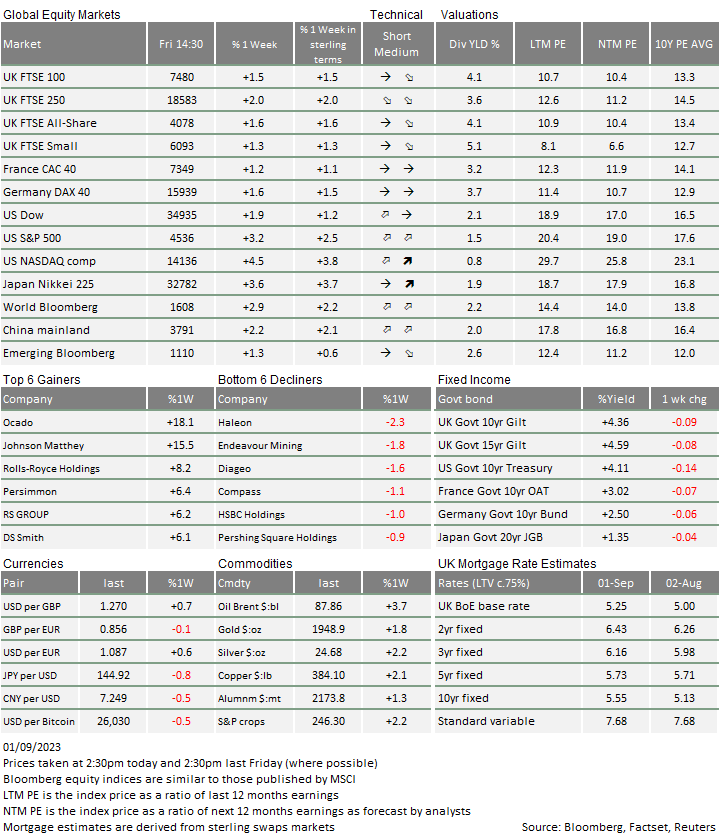

* The % 1 week relates to the weekly index closing, rather than our Friday p.m. snapshot values

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.